The Ox in Chava Shulamit

For the last few weeks, I’ve been quite pre-occupied with the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet. It’s a lonely subject, not one that inspires camaraderie and casual joshing over drinks. In fact, the presence of other human beings is a terrible distraction, even an imposition, when you’re itching to shut yourself off from the world and hunt down Canaanite clues and revisit the Phoenicians, in order to discover the origin of our own alphabet.

Despite my desire to return to the Canaanite past, every day the technological world and its evil twin, mass communication, came knocking at my door in its usual, modern, invasive manner. Not only did emails, Facebook messages, YouTube videos, cell phone texts, and UPS deliveries intrude, insistently demanding my attention but the printer ceased working, meaning I had to drop my work and spend hours plugging and unplugging cables so my son could print out his vocabulary words and biology notes. Asking him to rewrite them by hand didn’t cross my mind. It would have been tantamount to asking him to rewrite them in cuneiform.

I felt tyrannized by unwanted words and was thinking unkind thoughts about Gutenberg’s invention. Yes, the printing press had democratized knowledge by allowing the masses, not just scholars, access to books and information, but it also ultimately has been responsible for my spam emails, the inane television and radio commentary every New Yorker is now bombarded with on taxis, and the flash ads and pop-ups that I meet with almost every click through the internet. “Technology!” I huffed to myself more than once over the week. “This incessant exchange of information! Are all of these mediums of communication necessary to convey our messages, or do they just make this world noisy and excessively word-y”

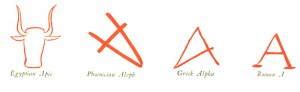

Each night I couldn’t wait to return to the quiet that I found in my private perusal of the origins of the alphabet which, I was aware, was responsible in large part for the very things I’d been complaining of. According to some scholars, the alphabet as we know it emerged in Serabit in Egypt in the 19th century BCE. There, illiterate Semitic workers copied Egyptian hieroglyphs that represented entire words – a square for a house, an ox’s head for an ox – and interposed upon that picture the initial sound for that word in their language. So, for example, when the Semite drew an ox’s head, it didn’t mean the head, it meant the “a” sound, for alp, ox in the Canaanite language, and the house was “b” for bayit. In this way, they didn’t need to memorize the hundreds of hieroglyphs in order to communicate. They could use less than 30 signs and mix and match and create innumerable word combinations.

This Proto-Sinaitic alphabet traveled around with its users, but retained the pictorial quality of hieroglyphs until about the 12th century BCE when it became standardized. The new letters bore little relation to the pictures they once represented. Eventually, but not right away, this Serabit script developed into a linear one and spawned the alphabet which would be used for Phoenician, Canaanite, Hebrew, early Greek and Latin and Western languages.

On Sunday, I took a break from both my proto-Sinaitic alphabet obsession as well as modern communication devices and drove down to Philadelphia for my niece, Jacqui’s, baby naming for her daughter, Charlotte. It was a lovely, warm, informal gathering of friends and family and entailed a little poetry and some Hebrew blessings. Near the close, Jacqui spoke about Charlotte’s Hebrew name, Chava Shulamit. They’d used the female version of her father-in-law’s Hebrew name, Chaim, and her grandfather’s, Shlomo, and arrived at Chava Shulamit, which means life and peace. Saying those men’s names evoked their presence in the room, and brought their images to mind. A simple word can conjure up an entire scene, and can allow one to mentally travel back in time: Jacqui’s grandfather loading the dishwasher in his meticulous way, or her father-in-law leaning back in the chair after enjoying a wonderful dinner, a self-satisfied smile on his face.

To an outsider, it might be impossible to find evidence either of Chaim Shlomo or of an “ox” in Chava Shulamit. But that’s the job and the beauty of language – to leap and change and transform an ox into an aleph into an “a”, to communicate the past into the present, to pass information down, to comport itself to meet the needs of its time, even while holding onto its origins. And, of course, that’s also the job and the beauty of babies.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Angela Himsel

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!