Urgent: Voters Needed. More Urgent: Overturning Laws that Disenfranchise Millions

Midterm elections are just days away. And like many in my community, I’m doing my part to get out the vote. We’re making calls, knocking on doors, and — because Minnesotans can register to vote on Election Day — we’ll keep going until the polls close.

In the 10 years I’ve worked in Jewish social justice, I’ve knocked on a lot of doors. I’ve had people yell at me, hug me, offer me a snack, and slam the door in my face. The hardest response to take, though, is usually, “I can’t vote.”

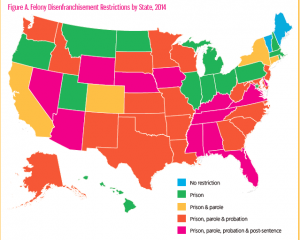

On Tuesday, almost 6 million Americans will be barred from the polls due to felony convictions. While specific laws vary by state, the US is the only country that allows states to permanently disenfranchise felons even after they’ve completed their sentences. In fact, of those turned away from voting next week, 75 percent are no longer in prison, and 2.6 million have served their entire sentence, which includes parole and probation.

In Minnesota, felons can’t vote until completing their prison term, parole, and probation. Nationally, we have the fourth-highest number of people (per capita) who are under some type of “community supervision” outside of prison. That means that the majority of our 70,000 disenfranchised voters have never even spent time in prison. Of those not allowed to vote, 87% currently “live in the community, hold jobs, and pay taxes”, according to the Minnesota Second Chance Coalition.

For people with current and former felony convictions, disenfranchisement is “a politically alienating experience that undermines political trust and diminishes political involvement,” according to a study by the Sentencing Project. In that study, more than two-thirds of respondents say that losing the right to vote is “personally upsetting” and “seemingly at odds with their understanding of democratic ideals.”

Further demotivating is the fact that, because policies differ by state and most felons aren’t informed of or educated about their voting rights, former offenders who may not understand the restrictions of their state may try to register to vote, in the process committing an entirely new crime.

Since 1997, 23 states have reformed and expanded voting rights, and an additional 800,000 voters have gained the right to vote. Studies show that most Americans believe in expanding voting rights to people with felony convictions. A recent survey found that 4 in 5 Americans support voting rights for citizens once they’ve completed their sentence, and almost two-thirds support restoring the right to vote to people who aren’t currently incarcerated, including those on probation or parole.

With popular opinion in our favor, I wonder why we’re not moving faster, why the reforms aren’t more expansive, why so many Minnesotans are still disenfranchised. I had coffee with a member of my community, who told me, “I think most Jews would agree that more people need the right to vote, but I don’t know if this feels that urgent right now.”

I thought about that and spent some time reflecting. I asked myself why I think it’s urgent, and why I want my community to care.

One of the things I believe, as a Jew, is that it is our responsibility to repair the broken world. I think we put this value into action in no greater way than when we work to end racism and to act as allies, in solidarity with people of color. Felon disenfranchisement disproportionately impacts people of color, especially African American males. Nationally, black males are incarcerated at more than six times the rate of white men, and one out of every 13 black Americans of voting age is disenfranchised due to a past or current conviction.

In Minnesota, 1 in 5 African American males are disenfranchised, as well as more than 6 percent of Native Americans of voting age. The city of Minneapolis is 70.2% white, but I live in one of the most racially diverse neighborhoods. The community I live in, where I send my kids to school, is 42% white and 34% African American. How can I know that the officials elected to represent us are hearing the voices of my neighbors?

The numbers are not evidence of a broken system, they represent the success of a system designed to keep people of color from fully participating in the democratic process, and designed to keep communities of color from achieving electoral power. After the Civil War, Southern states enacted disenfranchisement schemes targeting newly freed African Americans, and today — especially after the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act last year — we’re haunted by this shameful legacy. Felon disenfranchisement laws and amendments that would require voters to present photo ID, like the one we defeated in Minnesota in 2012, are proof that the system is working. It’s working in a way that perpetuates racism, injustice, and a broken world.

As a Jew and a Minnesotan, I see this issue as important and urgent. I believe we’re building a better and more peaceful society by working for elections that speak the truth about who lives in our country, that represent the voices of all invested parties. We need justice, and that means taking a hard look at who we’re incarcerating and disenfranchising.

Forgiveness — as JCA member and scholar Louis Newman described it in an article in the Journal of Religious Ethics, “Balancing Justice and Mercy: Reflections on Forgiveness in Judaism” — is “a moral gesture offered to the offending party as a way or restoring that person’s moral standing.” As Jews we are obligated to forgive, but forgiveness is not passive, it requires us to work to restore an offender to their place in society.

This resonates with me, the idea that forgiveness must be about restoring balance. A world out of balance will remain broken. There is no joy, no pride in being removed from the democratic process, from being told that your voice does not count, will not even be heard by those who represent you.

“I can’t vote,” is a sentence often said with shame. But the shame should be ours, and we must work to change these laws, for balance, and for a just world.

Carin Mrotz is the Director of Operations and Communications at Jewish Community Action, which is working as part of a coalition to restore voting rights to disenfranchised Minnesotans. On staff since 2004, she has worked on campaigns for immigrant and workers’ rights and played a key role in JCA’s work to pass marriage equality in Minnesota in 2012. She founded and staffed Indie Jews, an initiative to organize and mobilize Jews outside of congregations. Carin grew up in South Florida and lives with her family in Minneapolis.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Carin Mrotz

More articles in