The Metamorphosis: Jonathan Kis-Lev's Jerusalems

Entering the Art and Soul Gallery on Shlomtzion Ha-Malka Street, you exit Jerusalem. The curious visitor, stepping in from this busy street in the center of the city, is confronted with an exhibition of landscapes depicting a Jerusalem at odds with the reality outside. The Jerusalem outside is dirty, tense, and enraged; hot and cold; contentious and unjust; a wound sheathed in white stone. Inside, on the walls of the gallery, are calm and verdant provincial seats, quaint and homey mountain towns.

The exhibition, entitled “Of Gold,” is up-and-coming artist Jonathan Kis-Lev’s first solo show in Jerusalem. Born in 1985 to Russian immigrants, Kis-Lev was raised in a small village on the outskirts of Jerusalem. He has participated in a number of joint exhibitions in Israel, including “B-Sides” at the Tel Aviv Culture Conference and “Home” at the Apart-Art Gallery. “Of Gold” is part of a larger interest in urban spaces. In 2010, he was the youngest artist to hold an exhibition of landscapes of the city of Naharia, entitled “Naharia My Love,” at the Edge Gallery in that city.

Curated by Shiran Shafir Buchwald, “Of Gold” represents the fruits of Kis-Lev’s six years painting the city. The twenty-five paintings in the exhibition are gicleé reproductions of originals done in oil, retouched and enhanced by the artist. The gicleé process, first developed in the late nineteen-eighties, entails the digital photography and high-quality printing of works of art.

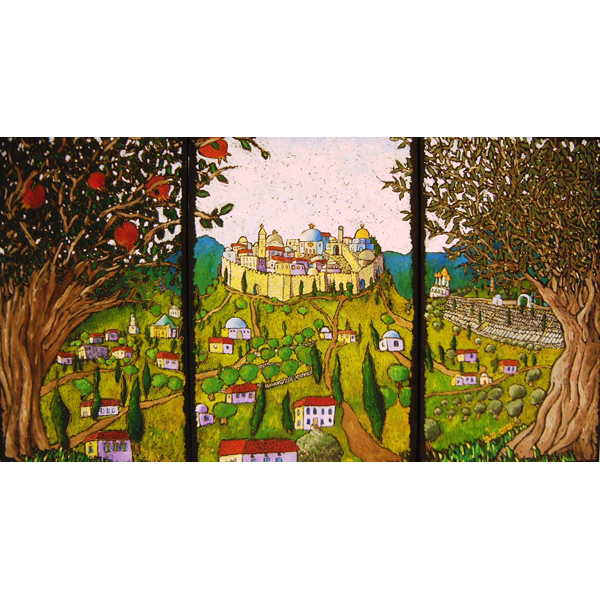

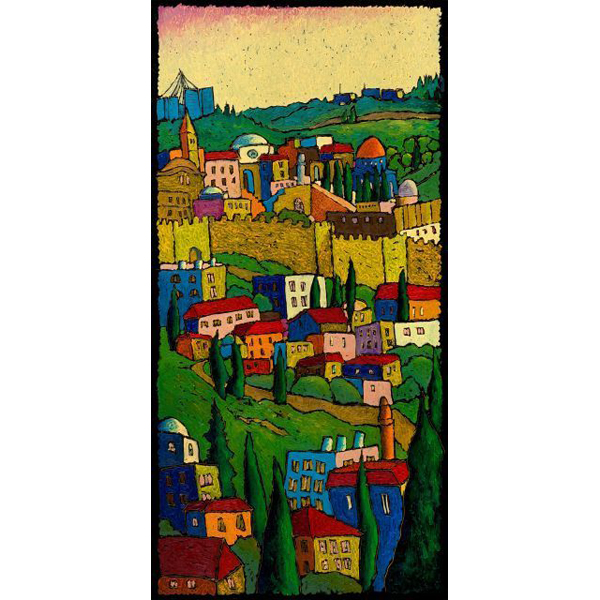

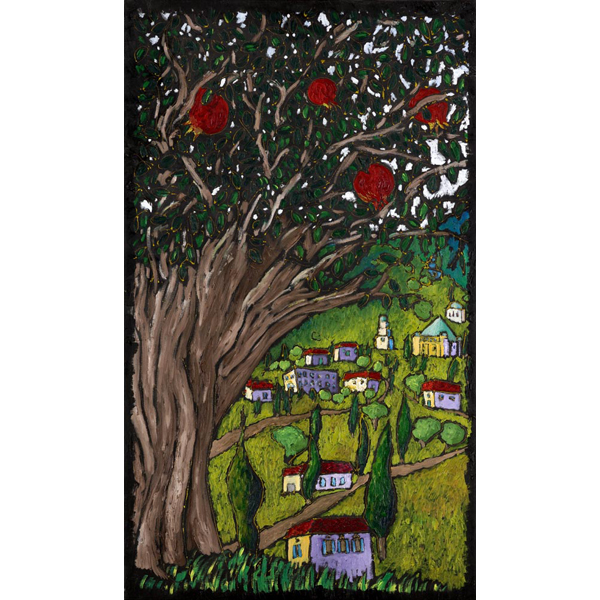

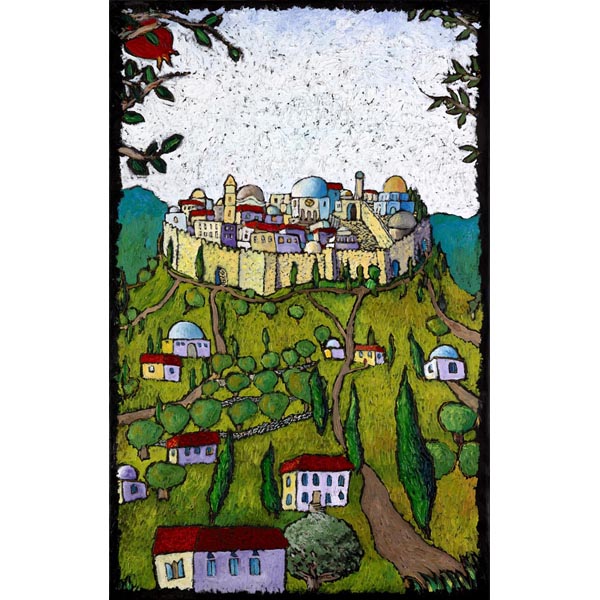

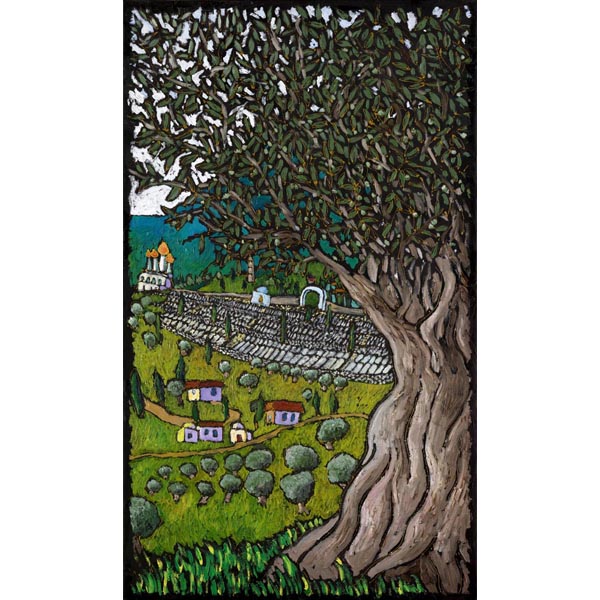

The first difference the viewer notices between the Jerusalem outside and the painted cities is that the latter are awash with green. These Jerusalems are blooming with fruit and flowers. In many of the paintings, the scene is framed by the boughs of fig trees or by bowls of pomegranates resting on a windowsill. The painted cities are less sprawling than our Jerusalem. The city is depicted as a small walled complex squatting on the crest of a hill, its outlying districts—hamlets, really—interspersed among fields of rolling green.

The landscapes are also surprisingly unpopulated, each depicting a city without inhabitants. There are no faces staring from the curtained windows, and the holy sites are empty of pilgrims. It is difficult to find the right word to describe the feeling of this emptiness; perhaps it is best to say it does not feel empty at all. Kis-Lev’s Jerusalems are not cities tragically abandoned. If one tries to imagine the people, it is difficult to know where to put them. Nowhere seems appropriate and no one seems to be missing.

Kis-Lev’s Jerusalems are also of another time, or of an alternate history. There are few of the modern buildings which define the city’s architectural landscape today. The luxury hotels and Israel Museum are nowhere to be seen. Less picturesquely, also missing are the separation wall and fortified settler complexes in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan. The very land on which these structures sit is occupied in the landscapes by grass and flowers. What is left among the fields and orchards seems to be the Old City and Yemin Moshe, the early Jewish settlement outside of Jerusalem’s ancient walls. This identification, though, is inexact. The dimensions of the city, the length of the walls, and the density of its satellite dwellings are inconstant, different in each painting and in all cases different than the proportions of the historical Jerusalem.

The city that remains is dominated by buildings that testify to its religious significance. In each, a church, a mosque and a synagogue is depicted prominently. Often, the three structures can be identified as the domes of the rebuilt Hurva synagogue, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount. Sometimes other religious monuments play a role—the onion-shaped spires of the Church of Mary Magdalene on the Mount of Olives are prominently featured in the “Peace on Jerusalem” triptych—but in all cases the ecumenism remains.

It is easy to dismiss these paintings as naive. Depicting the church, mosque, and synagogue as sharing the same urban space is not a replacement for, and will not bring about, a just solution to the violence and oppression that plague this city. That magical thinking is counterfeit coin. Nostalgic for a harmonious past that never was or envisioning a saccharine and unrealizable future, the artist can be charged with disengagement from the political reality of Jerusalem now – graft, poverty, demolitions, oppression, hate.

And yet, seen as sites of metamorphosis, as records of the transformation of the Jerusalem we know into another city, Kis-Lev’s work resists this interpretation. The dynamics of this metamorphosis can be fleshed out with the help of one of Franz Kafka’s shorter tales, titled simply “The Bridge.” Of course, Kafka’s writings are resplendent with metamorphoses; in addition to the entomological fantasy which bears that title, we find apes turned into distinguished lecturers and the horse Bucephalus becoming a studious lawyer. However, the story of the bridge stands apart. A lonely bridge which has never been traversed stands in wild country over a mountain stream. The bridge is at the same time, somehow, a human being, clutching one side of the ravine with toes and the other with fingers, hair splayed over the opposite bank and coattails flapping in the wind. When, at long last, a traveler comes to cross, instead of walking the span he jumps right to the bridge’s middle. Struck with pain, the bridge turns on itself to see the violent offender, as it turns falls and is dashed on the teeth of the rocks below.

The bridge’s is an ambiguous metamorphosis. As in so many of Kafka’s transformation stories, its true nature, human or architectural, remains undecided. We can think of the half-kitten, half-lamb that is the narrator’s inheritance in “A Crossbreed,” and the rider on his way to becoming a horse in “The Wish to be a Red Indian.” Even Gregor Samsa, as Valdimir Nabokov points out in his lecture on “The Metamorphosis,” is stuck between his human and insect natures. On that first morning when Gregor awakes on his segmented back to the sight of his multiple wriggling black legs, he can still humanly blink—insects, of course, lack eyelids—answer his mother in his normal voice, and, once he wriggles from bed, stand anthropoid on his two back legs.

The same ambiguity can be found in Kis-Lev’s landscapes. Certain elements from our city seep through to these bucolic Jerusalems. In a few images, buildings appear which are characteristic of the current city: the long neck and strings of the Chords Bridge in “Jerusalem at Dawn” and the tower of the Hebrew University on Mt. Scopus in “Jerusalem, the Holy One.” In both cases these structures sit discreetly on distant hills. Despite their unobtrusiveness, the presence of these elements mark both the transformation underway and highlight its incompleteness.

Aside from this ambiguous metamorphosis, Kafka’s stories share with Kis-Lev’s paintings the shape of a parable. In classical rabbinic parables, or in Jesus’ parables in the New Testament, each character in the fictional universe signifies a corresponding element on the cosmological or theological-historical plane. The king is God, the daughter is the Torah, the pearl is Wisdom, the wise son is Israel. “The Bridge” speaks in the language of parables, with its fantasy and verbal economy, and has launched a fleet of interpretations claiming to decipher its signs. The traveler’s thrusting of his pointed walking stick into the bridge’s bushy hair has been read as an allusion to sex, and the entire story as an expression of Kafka’s sexual anxieties. The tale has also been understood as a meditation on metaphor itself, in particular metaphor’s inherent failure to bridge the gap between figurative language and meaning.

The story, however, resists each of these readings. As much as the elements in “The Bridge” seem significant beyond the story’s surface level, it remains unclear what the tale means to signify. Walter Benjamin argued in his essay on Kafka that stories like “The Bridge” are never exhausted by what is explainable. Benjamin writes: “they are not parables, yet they do not want to be taken at their face value, they lend themselves to quotation and can be recounted for purposes of clarification. But do we have the teachings which Kafka’s parables accompany and which K.’s postures and the gestures of his animals clarify? It does not exist; all we can say is that there we have an allusion to it.”

Though Kis-Lev’s paintings resemble religious icons, populated with sacred symbols infused with inner light and adorned with gold, they too do not resolve in easy interpretation. The three holy monuments which dominate the paintings seem, again, to point to a message of religious pluralism. However, how should one interpret the city’s altered and diminished urban landscape? In “Song of Divinity,” in addition to the verdant trees and flowers, the dwellings of the Old City that dominate the image are pictured with incongruous red roofs, as if transplanted from a Galilee kibbutz. Perhaps we are seeing a Jerusalem of the distant past or future, perhaps another city caught in the act of becoming Jerusalem. The unpopulated spaces—most prominent in “Sunrise Over Jerusalem,” where the absence of people from the windows, gardens, and forking paths is most striking—could point to the impossibility of these cities and the harmonious dream they seem to naively promote.

Like “the Bridge,” the painted Jerusalems are primed for a meaning which slips through the fingers. That seems to me to be precisely the point. We miss the meaning because it has been amputated. The images depict Jerusalems which have become mundane, detached from heaven, sundered from holiness. Only in such a Jerusalem could mosque, synagogue, and church equally and peaceably divide the horizon. These are Jerusalems become so unimportant that the streets are empty. It is a backwater city, a provincial byway, a stop on the road. The viewer’s perspective is that of a traveller who sees the sleepy city from afar, takes in the greenery and quaint stones, and moves along.

Kis-Lev has painted a demythologized city, a de-messianized Jerusalem. This point too he shares with Kafka. The writer’s greatest and most well-tuned stories of transformation inhabit this same reclaimed secular space. Alexander the Great’s steed Bucephalus, for instance, in the story “The New Advocate,” has become a lawyer at the bar. “In the quiet lamplight,” Kafka writes, “his flanks unhampered by the thighs of a rider, free and far from the clamor of battle, he reads and turns the pages of our ancient tomes.” Myth is dead, and in its absence, the beasts, heroes, and shrines can take up ordinary pursuits.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?