Birthright's Israel: The Political Bias of the Jewish Community’s Favorite Program

As a beautiful Spring Sabbath in Israel came to a close, groups of tourists were sipping Goldstar beer, watching the sky darken over the Sea of Galilee, when suddenly an approaching ferry tarnished the tranquil scene in a fog of pyrotechnics, strobe lights, and loud music. A voice prevailed through the vessel’s PA system.

“On behalf of the People of Israel and the State of Israel, we would like to welcome Birthright, Taglit, to Tiberias and to the Sea of Galilee and express our deepest appreciation for your love, support, commitment, and friendship to Israel!”

A group of 120 mostly drunken and somewhat Jewish twenty-somethings emerged elatedly from the crowd of vexed tourists and proceeded towards the floating disco, myself amongst them. When you’re with Taglit, this is just how you roll; in a Birthright bubble.

Taglit #357

A week and a half prior to the booze cruise in Tiberias, I was in a taxi on the way to JFK airport where there was a free round trip ticket to Tel Aviv with my name on it, along with those of 38 other young Americans. Birthright Israel’s stated mission is to bring young adults to Israel to “strengthen the sense of solidarity among world Jewry, and to strengthen participants’ personal Jewish identity and connection to the Jewish people.” Birthright is widely thought to be among the most successful Jewish outreach programs, particularly for less affiliated Jews. While sitting on the tarmac, meeting and greeting my fellow travelers, I found out that with the exception of myself, nobody from Trip #357 had come from a remotely religious setting. Fifteen hours later we arrived at Ben-Gurion airport where we met our trip leader, an Israeli-born freelancer I’ll call Avram. (Names of all Birthright staff and affiliates been changed for privacy.)

Birthright trips are a joint effort between Birthright and a contracted trip provider. Birthright controls 40 percent of the trip’s planned activities, which are mostly lectures, tours, and discussions. The other 60 percent of the itinerary, the more action-based portion of the trip, is planned and managed by Birthright-approved trip providers. This permits Birthright to bring tens of thousands of young Jews to Israel every year without having to run the adventures themselves, while simultaneously controlling the tone of the trip.

We arrived late on a Friday night to our first destination, Jerusalem. Many of the people in our group had never kept the Sabbath before, and were startled by the silence of the streets. The following morning our jam-packed itinerary would already be underway, as the entire history of the Middle East was unleashed upon us after breakfast by a designated expert, Ned Lewis. Lewis is a bright, humorous man, who travels the world to engage in what Israelis call hasbara, the Hebrew word for setting the record straight on the situation in Israel (The literal English translation is “propaganda.”). As Lewis sees it, misinformation, stemming in large part from poor public relations on behalf of Israel, and a latent international anti-Semitism has distorted the facts on the ground. After some helpful anecdotes to characterize the culture of this still-developing nation, including one about a Bedouin he saw steering a camel with his left hand and operating an iPhone with his right, Lewis’s lecture takes on a blatant political bias.

While describing the political climate in Israel, Lewis repeats the words, “it’s complicated,” until it becomes a mantra, all the while presenting Israel’s predicament simplistically: if Israel gives up the West Bank it will be nine miles wide at its narrowest, making it highly vulnerable to a potentially devastating attack by one of its surrounding adversaries. Lewis presents Israel’s unilateral military pullout from the Gaza strip as a diplomatic peace offering made by Israel, omitting any mention of the effect that the blockade has had on the quality of life for those who live in Gaza, which many deem to be a humanitarian crisis. Lewis also tells us that the Palestinians living in the West Bank live the same lifestyle as the Israelis with one exception: “I imagine if I were pulled over every now and then and asked a bunch of questions,” Lewis says, referring to the military checkpoints to which Palestinians are subjected, “I would get sick of it too.”

Over the course of his lecture, Lewis carefully constructs a connect-the-dots portrait of the Middle East, while encouraging all of us to form our own opinions. Connecting dots, however, is a method used to trick children into believing they are drawing something, when ultimately the picture has already been depicted by the artist. Based on the dots Lewis provides, there is only one conclusion we non-experts in the Middle East could have drawn: an Israel that does everything in its power to achieve peace with its Arab neighbors, who are unfortunately hostile and hateful.

For the majority of us in group 357, who have come to Israel knowing little of its history, Lewis’s lecture will serve as our educational foundation of the Middle East, and will be repeatedly referenced by Avram for the remainder of the trip. At the time, I was perplexed by Birthright’s decision to choose such a blatantly conservative authority to educate us Birthright tourists on the state of the Middle East. But my perplexity has since dissipated.

Birthright Foundations

In order to fund “the largest Jewish Educational program ever,” as Leonard Saxe, Director of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University, phrased it, the Birthright foundation requires deep pockets. The money comes from three sources: private philanthropists, American Jewish federations, and the Israeli government. Birthright was founded by Michael Steinhardt and Charles Bronfman, two major Jewish philanthropists, both of whom are members of what is called ‘The Mega Group,’ a billionaires club that donates large sums of money to Jewish organizations like Birthright and Hillel, as well as to political groups with conservative leanings, such as The Foundation for Defense of Democracy (FDD).

To conduct its public relations, Birthright has hired 5WPR, a PR firm that has represented a host of clients that espouse views on the far right of Israeli politics, including Christians United for Israel, an organization whose founder, John Hagee, recently spoke at Glenn Beck’s “Restoring Courage” tour of Israel, and who has said Hurricane Katrina was caused by “homosexual rallies.” 5WPR’s client list is an unsavory conglomerate of characters and businesses including Mantra Films, Inc., the soft-core porn production company whose Girls Gone Wild series has accrued multiple lawsuits for depicting underage girls, and Agriprocessors, Inc., the glatt kosher meat packing company that has received multiple citations for animal abuse and violations of both child labor and environmental laws, and whose former CEO is now in jail. (5WPR’s strategy for repairing Agriprocessors Inc.’s image relied heavily on fraudulent tactics that it has since acknowledged in light of irrefutable evidence). Even more telling, 5WPR’s CEO, Ronn Torossian, is the founder of Yerushalayim Shelanu, “Our Jerusalem”, an organization that works to attain court-ordered evictions of Palestinians from their homes in Jerusalem. In a 2004 interview with The Forward, Torossian said, “The PLO or P.A., or whatever the gangsters call themselves today, have no place in Jerusalem,” and in an interview with Jerusalem Post in 2009 he made the comment, “This isn’t a war between two equals; it’s a war between a civilized democratic nation and a group of murderers and terrorists.” This is the person heading Birthright’s PR team.

The Trip

The trip itself was a blast. The 12 days were loaded with activities: An early morning hike up Mount Masada; a float in the Dead Sea; a bike ride through the Judean Desert; a prayer at the Western Wall; a visit to Yad Vashem; and hours and hours of riding a coach bus, bonding both with other Jews and with the land itself, from the barren desert of the south to the rolling hills of the north.

Lewis’s lecture was not the only history lesson that felt more like propaganda. On day six of the trip, before heading south to the Negev, we were taken to Independence Hall in Tel Aviv, the place where Israel declared its independence in May of 1948. Here, a tour guide provided us with a history of the pre-Israel landscape, characterizing the area as an unpopulated sand lot until the Jews began settling it. This was something I had heard in the course of my Jewish upbringing numerous times, and only began to question in the aftermath of my Birthright experience. It wasn’t until I did my own research that I realized that this was not the only point of view. The U.N. census reported in 1947 that there were 1.2 million Arabs in Palestine, and 600,000 Jews.

After being shown a few montages displaying the pre-statehood Israeli army and a pensive but strong Theodore Herzl, the tour guide ushered us into the room where the actual declaration was signed. “Don’t worry about the facts,” the tour guide said, before playing an audio recording of David Ben Gurion’s voice reading the declaration 62 years ago. “It’s about emotions.”

Then there was that moment after the rowdy booze cruise on the Sea of Galilee, while the members of 357 took the dance party ashore, I wandered over to a small patio bar where I struck up a conversation with a friendly Palestinian man named Jamil. Aside from brief exchanges, this was the only social interaction I would have during the trip with someone unaffiliated with Birthright, and it became a memorable one. When our guide, Avram, announced that it was time to leave, I encouraged Jamil to walk with me towards the bus so we could continue our conversation. But as we got close, Avram spotted Jamil, and shouted at him to leave the area. When Jamil did not immediately comply, Avram became increasingly aggressive in his efforts to separate us, finally pushing me onto the bus and with the help of the driver, forcibly removing Jamil from the area. Though I know Avram was doing his job, and acting out of concern for our safety, the fact that this was the outcome of my one conversation with a Palestinian while on Birthright was further indication that there was an intended veil placed over the Taglit Israel tour, manipulating our experience of the country. It was this moment that that made me realize that in order to gain any insight into the Palestinian and Israeli conflict, I would have to see the country on my own. And so I did.

Birthright’s Omissions

I extended my trip. After our final day at the holocaust museum, I backtracked to the places I had just been. First, I went back to the old city in Jerusalem to visit the Arab and Christian Quarters and to see the Jewish settlements in the predominantly Arab, but Israeli occupied, East Jerusalem. There, I visited the Arab neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, where in the aftermath of a 2009 court ruling, Jews have been successful at evicting a number of Palestinian families from their homes. While there I witnessed a procession of Jewish activists demonstrating their outrage over a recent court-ordered eviction of a Palestinian family. Jewish settlers had since moved in to the previously Palestinian-owned house and erected a giant menorah on the roof. Jewish right-wing activists were also on the scene, a group of whom were holding up a sign praising Baruch Goldstein, the Jewish terrorist who killed 29 Palestinian civilians in Hebron in 1994.

I also visited my American but Israeli-born friend, Yehuda, a 28-year-old who, after college, returned to Israel to volunteer for the Army. I was anxious to hear about his experience as a chayal boded, a lone soldier, who serves despite not having any family residing in Israel. I was very surprised to hear what he had to say. Yehuda told me that a lot of his combat missions as a soldier in special forces were meant to antagonize Palestinian civilians. He said it was not uncommon for his unit to needlessly obstruct commuters at check points or go into neighborhoods with armored vehicles blaring sirens and shouting Arabic into loudspeakers, their only aim being to provoke a response that would give them reason enough to fire their weapons. On the whole Yehuda said that from his observations during his service, and from his continued study of the history and politics of the Middle East at the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzeliya, where he was getting a Masters degree, he had not only become disillusioned by the Israeli occupation, but felt that it was becoming (in his words) an apartheid state, and as such he did not want to remain there any longer. Of course, these were just Yehuda’s opinions, but they were alarming to hear. It was only a handful of years ago when we had just graduated college that I listened to him explain to me with such conviction his reasons for wanting to fight for Israel and to live in the Jewish homeland.

During my last few days I ventured beyond the barrier wall into the West Bank, visiting the cities of Ramallah, the West Bank’s political and economic center, and Hebron, the traditional burial site of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, and Leah. I had apprehensions about crossing over the wall and into the territories. Having been educated in Jewish day schools in my youth, I grew up being shown videos of Palestinian children throwing rocks at Israeli soldiers. But then again, I thought, if Birthright’s chosen Middle East lecturer Ned Lewis were telling the truth, that the only difference between life inside and outside the pre-1967 border in the territories of the West Bank were a couple of little checkpoints, then I had nothing to worry about. Ultimately, I could not curtail my curiosity. Between media slants, peoples’ politics, education, and upbringings, the only way to acquire a remote understanding of what the occupied West Bank was actually like was to catch a glimpse of it with my own eyes. On my way to Ramallah, as soon as I crossed over the border, Israel Phones, the phone company Birthright contracts with to outfit its participants with rented cell phones, called me to ask why I was in the West Bank, and if I was all right.

At first Ramallah felt very similar to some of Israel’s older cities. There were lots of people about traversing the markets, coffee shops, nargillah cafes, and falafel joints. It wasn’t until I asked my host, 34-year-old, Samer, a beauty products shop owner, if his daily life was affected by the occupation that I could see that anything was amiss. Samer drove me to the city limits, and circled the periphery of the city pointing to the hills that surrounded Ramallah’s outskirts and to what was perched on top of them: rows of new condos and complexes. Samer explained that these were Jewish settlements and that he did not know how far into the distance they extended. Much of Ramallah abruptly and eerily dead-ended, and any roads leading up to the settlements were only accessible to Jews. Samer and a few of his friends told me that their day-to-day lives were fairly normal, but because leaving the city to go even 10 miles often took hours upon hours and was sometimes even blocked altogether–the gridlock caused by the Israeli check points (it had taken me 2 hours to go the 12 miles from Jerusalem to Ramallah)–they sometimes felt like they were being held captive in their city.

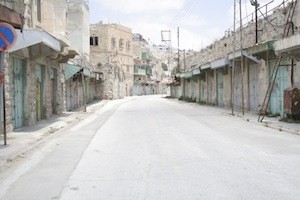

Next I went to Hebron where the tension between Israelis and Palestinians is so prevalent it permeates the air and wafts through the streets like a thick humidity. I could see Israeli soldiers positioned throughout the city, even hovering above it on lookout towers. Below the soldiers, occupying the tallest buildings are the homes of Jewish settlers, and below them are protective (Palestinian-built) nets drooping under the weight of large pieces of debris that Jews have hurled down at their Palestinian neighbors. The result is a network of trash-filled nets that hammock over the old city’s narrow stone alleyways. The once bustling market is now almost completely vacant, the economy left for dead. Outside the old city, Hebron feels like an outdoor prison. The main street is lined with boarded up and barred shops and is nearly desolate as it is closed to Palestinian vehicles and pedestrians. The Palestinians appear tired and fearful; Jewish settlers are permitted to walk the streets unimpeded with AK 47’s, while Palestinians are prohibited from carrying arms.

Of course, I could see Israelis suffering as well. I journeyed out to Hebron on a Sunday, when all over the country Israel’s moms and dads can be seen saying goodbye to their young sons and daughters, as the Israeli youth, its future leaders, board buses to go back to their respective army posts after a Sabbath spent with the family.

The Point of Birthright

Towards the end of our trip I asked Avram and our volunteer American guides why no Arabs were invited to speak to us. They responded like a chorus: “this is not the point of Birthright.” The point of Birthright, they explained, was to connect Jews with Israel. And after all, they said, time was short. But after seeing Israel on my own, it became clear that Birthright was not just guilty of failing to provide differing perspectives on Israel’s current situation, but was bending over backwards in order to ensure that we never saw a balanced picture of Israel. Really, our Birthright trip did not take us to Israel. Instead, they took us to “Israel,” Birthright’s fictional narrative construct.

Now, just as American tour companies don’t take busloads of senior citizens to inner city Baltimore, Birthright does not need to take youngsters to the most precarious places in the West Bank, or any place they feel might be dangerous. But a portrayal of Israel that avoids all contact with Palestinians, never gives a glimpse of life on the other side of the Green Line, and resorts to propaganda, is ultimately harmful to its intended audience, and to Israel itself.

In its analysis of Birthright, the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies reported that Birthright participants were 50 percent more likely than non-participants to report feeling “very confident” in their ability to “give a good explanation” of the current situation in Israel. However, the “good explanation” that over 250,000 Birthright participants might provide to their peers upon returning home is one created by a disingenuous portrayal of Israel. It is a false explanation, not a good one. Birthright’s participants do not return home to tell their friends and family how important it is, not just for Israelis, but for Jews in general, to engage Palestinians and Muslims in conversations and diplomacy so that peace can one day prevail. Instead, Birthrighters return home better equipped to tell their social networks why all of Israel’s actions are justified, and how Jews are on a higher moral ground. Birthright is training right-wing activists, not informed and engaged American Jews. One thing pretty much every Jew and Palestinian would agree upon is that the status quo is both unsustainable and unacceptable. Yet at a time when Jews and Palestinians desperately need to find common ground, to learn to come together, Birthright is pushing us farther apart.

In a recent speech, distinguished Israeli author Amos Oz described the Jews as a people with “a culture of doubt and argument, an open-ended game of interpretations, counter-interpretations, reinterpretations, and opposing interpretations.” Is that what Birthright offered us? Did it have the courage to empower us to face the complicated truth of the Situation in all its gravity so we might grapple, discuss, and argue?

No. The 12 days of Taglit were an unforgettable blast, and one, free of charge, that I am very much grateful for. But we Birthright participants experienced Israel under a shroud, blinded to what happens just across the Sea of Galilee while we dance the night away and socialize on buses. This is ultimately counterproductive. Birthright has the potential to educate Diaspora Jews about the situation in the Middle East in a way that could potentially bring two sides closer to a conclusion they both claim to want—peace—but instead is serving to foster an even wider misunderstanding.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Nathan Ehrlich

More articles in