Wrestling with Esther: Purim Spiels, Gender, and Political Dissidence

Note: Zeek published this incredible essay six years ago, when we were located on a different website. For Purim 2012, we’re reprinting it here because we think it’s awesome and want you to read it. -Eds.

1. A Drag King’s Bar Mitzvah

In 1999 I won the Philadelphia Drag King contest with my portrayal of metal-head bar mitzvah boy Ben Hesherman, whose speech broke into a rendition of “Breaking the Law” by Judas Priest. Onstage, I told the crowd, “I don’t want to grow up be a man like my father or the rabbi or the Israeli heads-of-state. I want to be like David Lee Roth and Gene Simmons of KISS! Members of my community, friends of my grandparents, I hope you’ll support me. I don’t want to learn Hebrew, I want to learn to rock!” I stripped off a too-big suit to uncover leather pants and a sleeveless Metallica T-Shirt. Someone threw me a plastic toy guitar, and a star was born.

The truth is, at five feet tall, with short hair and chubby boyish looks, the character wasn’t a stretch: my family often jokes about how much I look like my dad at his bar mitzvah. The next year at the contest, I brought Hesherman back for a scandalous performance involving a rabbi, a rocker drag queen, tefillin, and some honey (so that the Torah should be sweet to me). The soundtrack was KISS’s “Charisma.” Some might find these performances disrespectful and sacrilegious, but for me, creating and performing as Ben Hesherman enabled me to come out to my queer community about my Jewishness in a celebratory and sexy way. At the same time, performing an explicitly Jewish masculinity provided a space for me to connect and celebrate with other queer Jews, offering a language for communicating my gender-queerness in a way that my Jewish community (including my parents) could recognize.

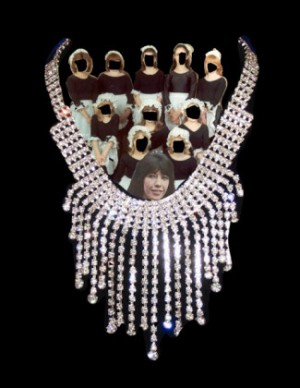

Somewhere in the haze of the glittery King’s crown, cross-dressing, and sweet treats I realized that my performances were inspired by memories of childhood Purim celebrations. As a child, I attended Purim parties dressed up as Esther in my grandmother’s costume jewelry and done up with blush and lipstick, which my hippie mother rarely used. The glamour of the Purim celebration was like a second Halloween to me. As a teenager, I gravitated to identifying with the character of Vashti as an icon of feminist resistance. At the time, my early queerness gave me a feeling of vulnerability, a sense that I could be thrown out of the community for being true to myself, as the King had exiled Vashti.

My experience of Purim as an opportunity for boundary-crossing transgression is nothing new; in fact it’s a very old tradition. The oldest surviving text of Yiddish Purim parody-plays (called Purimspiels) is a manuscript from 1697 known as the “Achashverosh-shpiel,” a play considered so vulgar at the time that it was burned by the government of Frankfort, Germany. In 1728, the government of Hamburg banned the performance of Purimspiels entirely. Today, purimspiels are common in yeshivas and religious communities. But the celebrations have also been reclaimed in recent years by Jewish feminists, queers, and progressives of all types, in part because of the possible feminist readings of the story and in part because of the topsy-turvy carnivalesque nature of some Purim traditions. These groups, marginalized by the mainstream Jewish community, are building on the rich history of Purim theater to create powerful spectacles and performances that critique, amplify, and challenge the politics of our times, the Jewish community, and the Megillah’s story itself.

2. The Shadow of Marginalization

A quick refresher on the Book of Esther: Ahasueros, the King of Persia, sends away his disobedient first wife Vashti, who refused to dance naked for the king and his guests. He holds a pageant for a new wife. A young Jewess named Esther (Hebrew name: Hadassah) enters at the urging of her uncle Mordechai and wins, having kept her Judaism a secret. Later, Mordechai uncovers a plot to kill the king by two eunuch guards. Through Esther, he alerts the king and foils the plot. Mordechai’s good deed is then recorded in the royal book of chronicles. Soon after, Mordechai refuses to bow to the King’s assistant Haman, stating that, as a Jew, he will not bow before a man. Angered and incensed at Mordechai’s being honored for saving the king’s life, Haman arranges to kill Mordechai and all the Jews in Ahasueros’s empire, with the blessing of the king. After a period of fasting and prayer, Esther saves the Jews by outing herself (as a Jew) to the king, who, while not rescinding his decree, allows the Jews to arm and defend themselves. Everything turns upside down: the Jews are victorious, instead of being annihilated; Mordechai is given the honored role that Haman had held; and Haman is hanged on the gallows intended for Mordechai.

That’s where the storytelling usually ends in Sunday school classes and Purim parties. But the Megillah actually goes on to describe a massacre of over 75,500 Persians, as well as Haman and his ten sons. The story of Esther and Mordechai’s heroism on behalf of all Jews is a great reason to celebrate, but how can we wrestle with the implications of the end of the story, the brutal vengeance-lust of the Jewish people, if we don’t even talk about that part of the scroll? The reality is that Purim is also about the shadow of genocide, marginalization, and hating “the other.” Amichai Lau-Lavie, whose drag character Rebbetzin Hadassah Gross appears annually on Purim, reminds us of the events of Purim 1994. That year, Baruch Goldstein massacred 29 Muslims, and injured a hundred more, who were praying at the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. Survivors of the massacre killed Goldstein, a member of the Jewish Defense League, and an IDF doctor. Israeli right-wing extremists see Goldstein as a holy martyr, claiming that he pre-empted the mass murder of Jews by Arabs. Witness the message on Goldstein’s gravesite:

Here lies the saint, Dr. Baruch Kappel Goldstein, blessed be the memory of the righteous and holy man, may the Lord avenge his blood, who devoted his soul to the Jews, Jewish religion and Jewish land. His hands are innocent and his heart is pure. He was killed as a martyr of God on the 14th of Adar, Purim, in the year 5754 (1994).

Those who eulogized Baruch Goldstein remembered his actions as a kind of “pre-emptive strike” against those who wish to kill the Jews. Did Goldstein see himself as a modern Mordechai? The 1994 massacre makes it clear that those of us who wish to celebrate Esther,Vashti, or Mordechai’s resistance to unjust authority must also deal seriously with the alternate Purim-interpretation of heroic vengeance and security-through-brutality, values that influence not only Baruch Goldstein and his supporters but also our own Israeli and American governments. By avoiding the end of the story, Purim revelers risk giving uncritical license to the fundamentalism and xenophobia found in the text.

In reality, the Purim story may never have happened. Scholars believe that King Ahasueros may have been the Persian king, Khshayarsha, whom the Greeks called Xerxes, and who ruled from 486 to 465 B.C.E. in Shushan, the capital Persian city. The descriptions of Ahasueros’ giant kingdom, which spanned 127 countries from India to Ethiopia, match the size of the Persian Empire under Xerxes, who was also known for his big fancy feasts and parties. On the other hand, no historic records verify the Megillah’s story, which has much in common with ancient romances, fairy tales, and other fantastic literature. As Rabbi Arthur Waskow writes, “Most Jews today understand the whole story of Esther not as an historical chronicle but as a novel.”

3. The Politics of the Party

Whether fact or fiction, the Purim story begs for modern critique, midrash, and creative re-visioning rather than the lazy revisionism offered by mainstream Jewish education. In 2003, I was one of the organizers of the “Suck My Treyf Gender” Purim party, an event which offered some opportunities for that creative critique. Suck My Treyf Gender featured hostesses from Hadassah Ladies for Homos (a sister organization of Church Ladies for Choice), a wrestling-match between Kosher and Treyf, and an alternative Megillah reading, all while raising funds for Jews Against the Occupation. At that event we distributed a manifesto, “The Politics of the Party,” which included this quote:

On Purim, we are religiously obligated to get so shit-faced [drunk] we can’t tell the difference between “blessed” haman, and “cursed” mordechai. Binaries, dichotomies, opposites are emphasized, exaggerated and celebrated. We masquerade as Good vs. Evil, Male vs. Female, Oppressed vs. Oppressor, but the goal is not to reinforce these dichotomies, but to realize that they are false separations, that there is a beautiful space inbetween all opposites, and that is the space where we live as happy, healthy beings. It is in between the extremes, somewhere between “male” and “female,” healing our experiences of oppression while checking ourselves on the power we have to oppress others, that we walk Hashem’s path.

In one act of this cabaret, I performed as Adam Shapiro, the Jewish guy who co-founded International Solidarity Movement (ISM) and who was with Yasser Arafat the previous Pesach in the Palestinian leader’s Ramallah compound, incurring the anger of the Zionist Jewish community. Adam and one of the Hadassah Ladies serenaded each other with “Wind Beneath My Wings,” in a celebration of the cross-pollinization of queer and anti-occupation Jewish activism. Another moving performance was offered by a woman who had recently returned from doing human rights work in the Occupied Territories and read poetry about her experiences that brought a powerful silence to the otherwise rowdy crowd. In sum, the Suck My Treyf Gender cabaret performances used Purim’s cultural traditions as a way to challenge the same nationalism and extremism that Baruch Goldstein glorified with his brutal killings. At the same time, we amplified the meaningful role of Jewish queers and outsiders. In our Megillah, the two eunuchs who plot to kill the King are among the symbolic heroes.

With the between-the-lines vision of Purim’s transgressive potential, we can ask real and deep questions. Is Esther a brave heroine or a subordinating woman spinning back and forth between the demands of various men in her life, making good for herself by capitalizing on the betrayal of other, stronger women? Is Mordechai a brave Jewish hero, or a patronizing and arrogant man who would gladly do to another people what he wished not done to his own? He won’t bow to a king, but he tells Esther to bow to her husband, the king. Is Haman truly evil, or was his history written by the victors who killed his whole people and needed to vilify him to justify a brutal “regime change”? Is Vashti the goyishe heroine of this Jewish story? Is the King really a fool, or, as many commentators suggest, the worst of all – a lecherous old man with access to endless virgins, eager to sign off on any genocide that doesn’t affect his property or his status? We have to wonder why those eunuchs were plotting to kill him, and look who starts and ends with the real power!

Modern Purim celebrations use the traditional play as a vehicle for popular education around a broad range of issues by playing with the iconic roles typified by the Megilla’s characters: good girl, bad girl, stupid king, valiant citizen, evil politician. These traditional players can easily and informatively be mixed up with any combination of modern kings, s/heroes, insider/outsider activists, popular resistance movements, and evildoers-ex-machina. For example, the Workmen’s Circle/Arbeter Ring, Amnesty International USA, HEEB Magazine, and Great Small Works once sponsored a “Giant Puppet Purim Ball Against the Death Penalty.” The celebration included a retelling of the Megillah and music and dance, including reggae with Yiddish lyrics, and the Klezmatics. In 2004, Great Small Works, Arbeiter Ring, and Storahtelling, joined with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice to create a play about immigrant rights directed by Jenny Romaine of Great Small Works and Circus Amok. In 2005, these groups reconvened at The Knitting Factory for a purimspiel that followed Vashti to a detention center and skewered racial “terrorist” profiling and the Patriot Act. These celebrations in Manhattan bring together amazing inter-generational crowds ranging from secular-socialist elders to queer red-diaper babies and all kinds in-between.

Purim’s tale is a warning with another warning wrapped inside, a liberation that isn’t liberating, and it begs us to create space for solutions that don’t entail easy answers. Wrestling with Esther offers her a chance for meaningful heroism without a brutal legacy, and the insights of these strategic theatrical misunderstandings offer us a path towards transformation

For those of us who don’t fit the mainstream Jewish community norms, Purim has become an opportunity to come out of the corners and challenge our own community by manifesting our fabulous otherness, our queerness. On all other nights, the institutional Jewish community displays a false homogenous front on the issue of supporting Zionism. And on all other nights, homophobia and transphobia are still prevalent in our community. On Purim those of us who, like Pesach’s wicked child, don’t tow those party lines, exhibit our politics and our true queer lives without fear of rejection and repression. (Or so we hope.)

The stage directions for the 2004 Immigrant Justice Purim Spiel offer some modern midrash that may allow us to harness the power of Purim to challenge fundamentalism in years to come:

Hadassah stresses that on Purim, if you are confused, you are doing the right thing. [She] knows there are many paths towards holy disorder, many routes to the mystical place of misunderstanding… The more we don’t understand, the more dyslexic we feel, the more we are entering into the practice of Purim, the more we will be supercharged, renewed, transformed.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?