Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

I squint at the prayer book lying open on my lap, its tissue-thin pages packed with rows of spindly Hebrew letters. They’re still a mystery to me, these curvatures — like the love child of Russian and Sanskrit — dancing into prayers that the congregation chants in calm unison.

“What page are we on?” I whisper to Rebecca, an old friend from Hebrew school. She wags her finger in mock disappointment and flips my book to the right page. An elderly woman cranes her neck and shoots us a silencing glance, her eyes lingering on my outfit a moment too long. I forgot to wear a prayer shawl and now my bare shoulders are attracting glares from censorious temple-goers. It isn’t the first time that I’ve felt out of place in an organized space for Jewish worship.

It’s a warm evening in the fall of 2013, and I’m at Congregation Beth El in Berkeley, California, to observe Yom Kippur. When I was a little girl, I dreaded the fasting period: My hunger pangs always seemed to make me more acutely aware of my transgressions. To escape services, my friends and I would scamper to the bathroom, cackling at our audaciousness and fantasizing about the food we’d eat, before slinking back. Those days, running into friends at temple was always the highlight of my experience. It still is.

Baruch atah Adonai, the congregation chants. When they begin a prayer that I don’t recognize, I reach into my purse and surreptitiously peek at my phone to check Facebook. After a couple of minutes, I catch my mom staring at me. I avoid her look, but I know that stare. It’s the reason that I stopped by services tonight, the reason that I would have come even if she hadn’t asked. Erica, her clear blue eyes ask, just how Jewish are you, anyway?

It’s a question that I’ve often asked myself. For many years, I’ve been uncertain about my Jewish identity and increasingly detached from the religion I grew up learning about in Hebrew school. And I’m not alone; in fact, my ranks are rising. “Among Jews in the youngest generation of U.S. adults [millennials], 68 percent identify as Jews by religion, while 32 percent describe themselves as having no religion and identify as Jewish on the basis of ancestry, ethnicity, or culture”, according the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life survey of Jewish Americans, released last year.

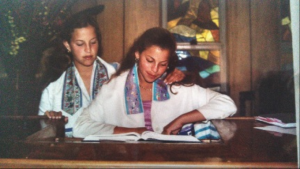

Courtesy of Erica Hellerstein

Erica Hellerstein (pink shirt) at her bat mitzvah. Pictured here with her sister.

For so many of my generation who’ve left behind more stolid, rigid Jewish practices, Judaism means something entirely different: it’s community-driven and participatory. For me, I’m just not sure. I’m not comfortable in either kind of space. And the older gatekeepers are right, at least as far as I’m concerned: I will never genuinely pray to the God of the Old Testament, nor would I teach my kids to do so. My own uncertainty and doubt torment me as I fidget through services, chanting to a God in whom I don’t believe because I don’t feel the strength to keep silent. In fact, I can’t wait to get out of there as quickly as I can.

Genie Dreams of Temple

On the same day, far away at Young Israel of Kendall temple in Miami , Genie Milgrom cradles a prayer book and settles into her seat contentedly. She is wearing a white skirt, a white blouse, white sneakers, and a white beret —“head-to-toe white,” she affirms. In Milgrom’s Orthodox synagogue, women wear white to free themselves from sin.

For Milgrom, who literally searched through ancient temples to find the truth about her ancestry, Yom Kippur carries deep emotional significance. “It’s my top, number one, most important holiday,” she says, adding that when she prays, “I fall into this semi-trance, almost like I’m taking all of my grandmothers and imagining their sheer suffering.”

Milgrom, who’s now 59 years old and living in Miami, told me her story over the course of several phone conversations. Though she’s now living in the United States and practicing Judaism, she was born to a wealthy Catholic family in Havana, Cuba, in 1955, when Fulgencio Batista’s regime ruled the island with an iron fist. The daughter of observant Roman Catholics, she lived in a spacious house with terrazzo floors. Fidel Castro’s revolution was just beginning to unfold, but what she remembers most are the lavish parties and masquerades of Havana’s grand old days.

When she was 5, her family, along with many other wealthy Cubans, fled the Cuban revolution and relocated to Miami, where she continued her Catholic education. But she found herself questioning some of the lessons that she was learning in school.

At the same time, she found herself drawn to a religion that was far from anything she had ever known: Judaism. As Milgrom came of age in the United States, she crossed paths with a handful of Jewish girls and with them felt an instant — and undeniable — connection. She was drawn to them “like a firefly to the light,” she writes in her memoir, My 15 Grandmothers. One summer at camp, she met Rachel, a Jewish girl who wore a thin gold Star of David necklace. Rachel fascinated Milgrom, who up until that point had never met a Jew or even heard the word “Jewish.” She spent hours grilling Rachel about the ins and outs of Judaism: the holidays, traditions, and tales of the Torah.

After that summer in camp, she was determined to find Jewish connections. And strangely enough, despite no real connection to the Jewish community, she says she felt comfortable in the company of Jews — more at ease among friends like Rachel than inside a Catholic church.

Years after Milgrom befriended Rachel, she was placed with a Jewish roommate while studying at a Catholic university in Miami. “There are no coincidences in life,” she told me firmly. Like Rachel, her roommate indulged her probing questions about Judaism and inspired her to study the Jewish faith in a handful of comparative religion classes. Though still immersed in a Catholic world, she insists she had already begun to feel her “soul stirring.”

Milgrom’s studies came to a halt when she married a Cuban Catholic man, had children, and lost herself in the family pharmaceutical business. It was not until years later, having split up with her Catholic husband, that she returned to her fascination with Judaism. She began devouring books on the religion and poking her head into local synagogues, wondering if this religion might be the right fit after all.

Milgrom wanted to convert, and spent several years studying, learning Hebrew, and attending services. Though she was thrilled to finally be on track to Judaism, it wasn’t easy to talk to her Catholic family members about her decision. One day, her maternal grandmother ushered her into a room and quietly cautioned her against converting, warning portentously, “It’s dangerous.”

She didn’t yield. Finally, the tedious process complete, Milgrom was welcomed into the Jewish faith. It was a joyous day for her — now she was officially Jewish despite her Christian roots. It was only after her conversion that she turned her attention to her family tree, which traces back to pre-Inquisition Spain and Portugal. Her maternal grandparents were second cousins whose ancestors came from Fermoselle, a tiny village in western Spain on the languid Duero River. Milgrom had always been interested in her ancestry and her Spanish roots, but her grandmother would change the subject whenever she asked about the family’s lineage, as if there were some sort of family secret.

One day, shortly after her grandmother passed away, Milgrom’s mother pressed a scuffed box into her hands, saying that her grandmother had wanted her to have it. She opened the box slowly.

Inside, she found an old, beat-up hamsa necklace and tiny Star of David earrings—two universally recognizable Jewish symbols. Suddenly, she was flooded with memories. She thought of the Spanish shawl that had been placed over her shoulders on the day of her marriage, a family custom still practiced by Sephardic Jews. She remembered the way that her grandmother swept the floor toward the center of the room, an old Sephardic tradition that requires sweeping away from the mezuzah.

Finally, she recalled her grandmother’s strange warning. It all seemed much more significant now. She wondered: Was my family Jewish? Were they forced to convert to Christianity after the Inquisition?

“There were so many clues waiting for me,” she told me. “My family just left me breadcrumbs.”

Synagogue to StubHub

Hours after the Yom Kippur services in Berkeley, I’m sitting in another row—at a soccer stadium in Los Angeles. The scene is a bit livelier than at services last night. Today, my temple is the StubHub Center, where I’m watching my (unobservant Jewish) boyfriend’s soccer team, Chivas USA, play the Portland Timbers. In Berkeley, my family is back at synagogue for services. Their stomachs are probably growling — after all, they haven’t eaten a morsel since sundown last night. Meanwhile, I’m munching on handfuls of grease-soaked garlic fries between gulps of beer.

I know that I’m supposed to be repenting instead of licking garlic salt off my fingers and watching my boyfriend grunt and sweat on the field. But I feel a strange sort of liberation in my defiance. Growing up, I was dragged to temple and Hebrew school, and my mind often wandered when my teachers recited the Torah’s tales of sorrow and redemption. I didn’t understand why they deferred to religion to answer questions that science and literature had already answered. The stories that I learned felt dated, hard to understand in the modern world.

“Do you really expect me to believe,” I asked one of my early teachers skeptically, “that Moses parted the Red Sea?”

Bagels in Miami

Back in Florida, Milgrom stays home while her second husband, Michael, an observant Jew, goes to temple. She prefers it that way: At home, she can pray in silence and serenity. The activity is “very private, very reflective, very solitary,” she says. Unlike me, she doesn’t use temple as a place to connect with friends.

“I don’t like going to synagogue because I’ll get distracted,” she tells me. “People will talk to me. I just want to pray.” While Michael is gone, she prepares a special meal for him: “Fried eggs and bagels,” she laughs. “I thrive on these holidays and this fabulous feeling of tradition.” She cites the sense of belonging and an incredible “pride to have returned to the Jewish people.”

After receiving her grandmother’s jewelry, Milgrom hired a professional Sephardic genealogist to research her family tree, telling him to concentrate on her maternal lineage and document his research with birth and death certificates when possible. Eventually, her maternal Jewish ancestry was traced to the 1400s, 15 generations back.

The documents tell the story. Like many Jews living in Spain during the Inquisition, Milgrom’s family members were B’nai Anusim — “Children of the Forced” — Jews who, fearing persecution by the court (or death), converted to Catholicism. The Spanish name for B’nai Anusim is converso, which literally means “the converted.” In medieval Spain, Jews who converted to Christianity were often discriminated against because they were believed to have impure blood. In Spanish, another term for converso is marrano, or “pig.”

Many converso families (Milgrom’s likely included) publicly practiced Christianity, but secretly kept up Jewish traditions. They were called “crypto Jews,” a name that originates from the Greek word kryptos (hidden). For hundreds of years in Spain, entire crypto Jewish communities existed in secrecy, celebrating the Jewish holidays underground in damp small basements and hiding all outward signs of Judaism.

But inside the home, crypto Jews pushed hard to preserve the Jewish faith. Milgrom’s research revealed that many of her cousins had intermarried and that quite a few had been priests. That was common in converso families, which often preferred to have a priest in every generation. They would perform the family marriages, but secretly omit something from the Catholic ritual so as to hold on to their Judaism.

As Milgrom’s curiosity about the hidden history of her family grew, she decided to visit the town of her ancestry, Fermoselle, to explore its winding cobblestoned streets and crumbling stone buildings. She wandered through the village’s ancient Jewish quarters and, five kilometers outside of town, encountered a stone chapel with ancient Hebrew writing carved and painted on the walls. She’s since become fascinated with crypto-Jewish wall paintings, and she searches for similar drawings in historic Jewish sites throughout Spain and Portugal to illustrate her lectures on the topic. One recent PowerPoint presentation was titled “Crypto Jewish Etchings in the Iberian Peninsula: When the Walls Speak.”

It’s been years since Milgrom uncovered her hidden past, but she’s still dumbstruck that a little girl from Havana, Cuba, who saw Che Guevara drive his daughter to school in a slick black limousine, could end up brushing dust off the walls of ancient prayer sites.

“When I converted, it was about finding the correct spirituality,” she says. “But when I finally found my roots, I felt an absolute need to take my place back among the Jewish people. That’s why I go around lecturing. It’s to say, we’re here, there’s a bunch of us, and we’re coming back. To whoever thought they had destroyed us, we’re coming out of the ashes.”

The Grassy Temple

It’s halftime at the soccer game, and a cluster of fans chatter excitedly, wringing their hands over botched shots and fumbled passes. Their children, who are just starting to learn the names and stats of every player on the team, stand near them in matching jerseys. A few chime in as their parents chant, humming the parts that they don’t know just like I used to do in temple. I wonder if for them, soccer is religion.

I take out my phone. “How r services?” I text my mom, the driving force behind my Jewish education. I was raised relatively observant, and my mother, who grew up in an Orthodox family, was strict about my Jewish upbringing. In her perfect world, I was to attend Hebrew school, have a bat mitzvah, and marry a nice Jewish man who practiced medicine. But my mom was aware that her family’s religiousness was slipping through the cracks. She was raised kosher; I grew up attending a Reform temple and routinely ate pepperoni pizza.

As I pushed forward with my Jewish education, I realized that my wavering faith was mainly a function of my doubt about some of the main principles of Judaism. To begin with, I don’t believe in God, and I wasn’t particularly attracted to the idea of a higher being shielding us from harm. Judaism also holds that there are 55 prophets identified in Hebrew scripture, and only seven are female. I wanted a better ratio.

My skepticism wasn’t the only thing that kept me from feeling passionate about Judaism. I also didn’t enjoy the top-down community structure. Some people find a deep sense of comfort when they’re in temple, congregating in a designated place, surrounded by people with whom they immediately have something in common. I’ve always preferred finding my religious community bottom-up.

Although I don’t believe in God or many of the Torah’s verses, there is much that I love about Judaism and being Jewish. When I meet another Jew while traveling, I often feel as if I’ve met a member of my own extended family. I also value Jewish ethics and many of the strong Jewish principles I was raised with have stuck, like tikkun olam. Growing up, the Jewish Law of Non-Indifference resonated with me: “If you see your fellow’s ox or sheep gone astray, do not remain indifferent. You must take it back to him … and so too shall you do with anything that your fellow loses and you find: You must not remain indifferent.” (Deuteronomy 22:1–3).

The careers of every member of my immediate family reflect this belief: My mother is a nurse, my father a doctor, and my sister a social worker. I also see echoes of Jewish ethics in my own career choice. The pursuit of good journalism, I find, is almost the opposite of indifference.

When I discovered Milgrom’s story, it seemed to magnify my own struggle with religious identity by holding it to a mirror against hers.

“What I find interesting is your voyage away from Judaism, and my voyage forward,” Milgrom tells me. “It’s almost like we’re two magnets.” Instead of being repelled, though, I am drawn to Milgrom’s story. I spend hours thinking about our different paths, trying to reconcile my doubt and skepticism about religion and spirituality with the power and conviction of her beliefs. Is there a profound message in her family story for me — an undeniable call of the blood?

I am much more fascinated by the Homeric crypto-Jew saga than by my own family’s relocation story from Russia to the United States, which was similarly driven by religious oppression. Both my dad’s maternal grandmother and my mom’s maternal grandmother are from Tetiv, a shtetl in Russia that had a population of 4,000 — a fact my parents discovered after they were married.

“I was worried for a second that we were cousins,” my dad jokes. While I enjoy the Tetiv story, I had never spent more than five minutes researching my genealogy online. And now here I am, huddled over my computer at 2 am, scrutinizing Milgrom’s family tree as if its curved and interconnected branches can somehow bring clarity to my own.

Keeping the Pride

Milgrom is the first to admit that the religious stakes are higher for her family than for most. She worries that if the next generation of her family rejects Judaism, her 15 grandmothers could be forced back into the ashes. Even her rabbi concedes, “The hope lies with your daughter,” despite the fact that her daughter has had a shaky relationship with Judaism over the years. Like me, she isn’t religious and doesn’t go to temple. But recently, after starting a gig in the kosher division of a catering company, she’s been calling Milgrom with questions about Jewish dietary rules.

To Milgrom, it’s the first sign of hope that the religious identity of her family may last another generation. And though, she says, her daughter never actively sought out her religion, “she’s become the kosher maven over there. She said, ‘Mom, is that ironic or what?’ And I said, ‘No, I just think your past is coming around and hitting you in the face and all your grandmothers are just circling you and circling you….’ It’s interesting that she is not searching for her identity, and her identity has come to her.”

As for me, my identity was never lost and never will be. But unlike Milgrom, I didn’t go from studying history to praying. Instead, my path has been the reverse: away from the prayer book and toward the history book.

I’m sure that Jewish ethics and learning can and will persist in the absence of a belief in God. But I didn’t come to this realization by sitting through services or struggling over complicated Hebrew verses in temple. I found it by doing something much simpler: writing this piece. Studying Milgrom’s family history didn’t change my relationship with religion or God, but I can’t deny that her story made me feel proud of something. It took me some time to unpack that pride, to understand that its roots lie at the bottom of the collective Jewish family tree. Milgrom’s story helped me realize that I have my own way of being Jewish. For me, it’s carefully studying our history and community, not praying beside a flickering candle.

A reverence for the Jewish community need not be built on a belief in the God of the Old Testament. It feels like the less time splitting (curly) hairs over who’s “cultural” and who’s “religious,” the easier it is for people like me to ask questions and learn what it is that has meaning. Like Milgrom, I have many grandmothers stretching back through time, and I will not forget them. What I have learned from her story is that through participating in the preservation of Jewish history and culture, I can keep the pride alive as well as religious Jews do, though in a completely different way.

I didn’t expect to come to that conclusion when I began writing this piece. But when I told my story alongside Milgrom’s, something surprising happened. My perspective changed. The elements of Judaism that I had always been drawn to — the tremendous community, the powerful history of oppression and perseverance, and the commitment to making the world a better place — boldly stood out, and I could see just how much they have shaped me. By studying the incredible history of a group of hidden Jews I knew little about, yet without embracing Milgrom’s newfound orthodoxy for myself, I have finally figured out a way of being Jewish that works for me — and might be an option for other nonreligious young Jews.

Jews may be the “people of the book” — but I know that my next chapter won’t be based on the prayer books that I stumbled through in temple. I’m more interested in the history books. And now I see that the door of the community has never been closed. For a long time, I just couldn’t see what was in the room behind it.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Erica Hellerstein

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats