Slavery and the Holocaust

One of the meanings of art is that it reflects the experience of the artist. Great art connects personal to universal experience by any number of gendered, religious, ethnic, and racial bridges.

In Jewish history, no experience is weightier than that of the Holocaust. But Primo Levi makes the observation in his last book, The Drowned and the Saved, that there is no such thing as the Holocaust Experience. Aside from the notion that no two people experience anything the same way, the experience of Sobibor was not that of Treblinka; Sachsenhausen in Winter, 1941 was not Sachsenhausen in Spring, 1943; in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bunker A under Kapo A was not Bunker B under Kapo B.

In Black history, no experience is weightier than that of slavery. But Richard Rubenstein notes in The Cunning of History how different the experience of slavery was in North and South America. The treatment of slaves and thus the anticipated time curve of their survival were different.

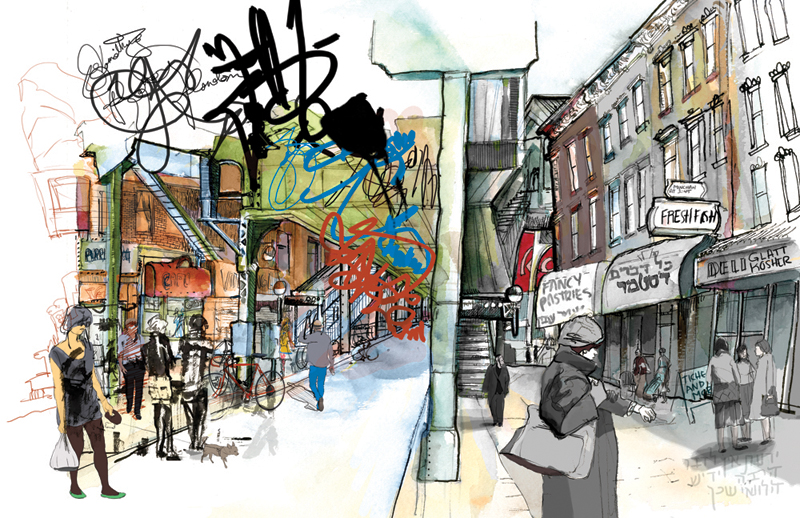

How much the more so in comparing the experience of Jews and Blacks—for which the Holocaust and Slavery are merely subsets of experience, however important. Thus an exhibition of work by Jewish and African-American artists might be expected to offer a range of images in a variety of media, reflecting not only individual proclivities and styles but diverse approaches to the historical experience of the two groups. The exhibition, Transcending History: Moving Beyond the Legacy of Slavery and the Holocaust, at Vivant Art Collection in Philadelphia, does just that.

Organized by the Idea Coalition, the exhibition offers 50 works by 30 different artists, Black and Jewish, in a deliberate attempt to highlight both parallels and distinctions between the experiences of two groups who have moved through history on parallel tracks—in both pain and response to it. In this exhibition, those tracks intersect—in four directions.

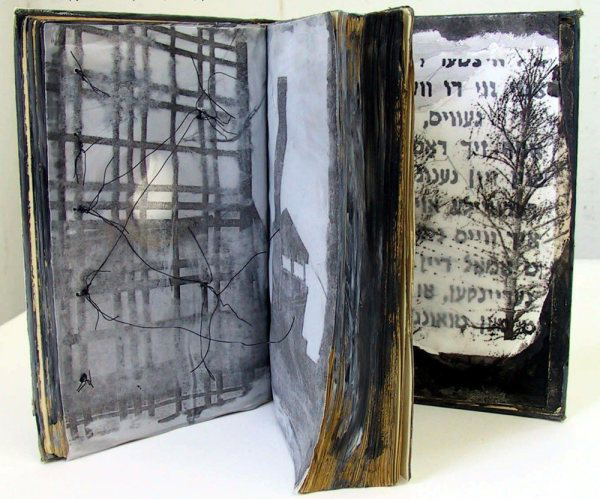

Then: Agony. David Wander’s “In Every Generation” centers on the image of a striped Concentration Camp uniform with its yellow star, flanked by a Hebrew inscription. From the Passover Haggadah—the annually read and sung Jewish “Book of Telling”—it offers the three words of its title, highlighted in being separated from those that continue them in the Haggadah, enjoining us to tell our children of our experience of slavery in Egypt—not that of our ancestors, but ours, for the experience transcends past, present and future.

Is it any wonder that the biblical story and liturgy recalling the Israelites in and emerging from slavery inspired earlier generations of African Americans in and out of slavery? Ayinde Green’s nearby wordless images tell the latter story. One of these is a shirtless man sitting in a chair, but the abstract patterns that decorate his back suggest the whippings that were his frequent fare. The yellow color that suffuses those marks seeps up into and fills his head, suggesting the power of pain-filled memory—and echoes the yellow of the star in Wander’s image.

Now: Exploitation. Yona Verwer’s “Star Amulet” from her Kabbalah of Bling series turns that star into an iridescent protective symbol, surrounded by a circle of completeness and perfection, ensconced in a hexagram. The power of symbols—in this case, “sixness” recalls both the Holocaust’s Six Million and the six words (in Hebrew) of the quintessential statement of Jewish connectedness to God: “Hear Oh Israel, the Lord is Our God, the Lord is One”—to serve as sources of both introspection and protection (what is called “Star of David” in English is called “Shield of David” in Hebrew), on what is a large piece of conceptual bling.

The Bling series, in its overall title, is intended to merge the deeply spiritual with the banal (“Kabbalah” and “Bling” should ordinarily be mutually contradictory). Verwer’s work is juxtaposed with the hip-hop banal and its potential power of high-flown words and ideas, in Shawn Cupid’s ironic “Darky Brew”—a found-object statement on street-life—and “So Ghetto”: a softly aggressive portrait of a young black man of the streets, cap over one eye, large, smiling mouth filled with blinged teeth. The black and red colors, in Italian Renaissance art, symbolize purgatory: the painful road from hell to heaven—or is it from ghetto streets to Main Street?

Then: Legacy. Infinitizing blocks of cemetery stones, filling an endless (Ahron Weiner’s) “Wall of Memory,” are juxtaposed with infinitizing rows of faces (Teela Banker’s “The Justice Seekers”). Soaring and richly-hued semi-abstract canvasses, like Rebecca Schweigers’ “Shedding Layers Healing Wings,” hang on the wall across Then: Agony, below the words Now: Resilience. Many more stimulating works extend the exhibit’s varied statement of the continuous resilience of two peoples with often painful, yet soaring, richly-hued histories.

If Jews and Blacks have moved on parallel tracks and those tracks intersect here, the exhibition asks the question: how can such an intersection offer a starting point for a new coalition of ideas and actions, to improve the lives of both groups and all groups, in Philadelphia and elsewhere. It is an important question, addressed in terms both visually eloquent and intensely thought-provoking.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?