The Jewish Picture Book: Storytelling as Midrash

I treasure the childhood memories of my mother telling my siblings and me her own variations of fairy tales like “Hansel and Gretel,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” and “Three Little Pigs.” There were picture books when I was growing up in Mexico City in the Sixties, but I have almost no recollection of them. The only title I do remember having been exposed to before I reached the age of five was a Spanish version of Winnie-the-Pooh. That I can’t remember these artifacts might be to some extent a result of my own faulty memory. But I also attribute it to the fact that the children’s book industry in the country was incipient at the time. To this day the number of picture-book titles published annually is less than twenty. The number is minuscule when one considers that Mexico has a population of over a hundred million.

As a Jewish boy, I was acquainted with illustrated volumes that featured fables, Bible stories geared for Christian children, Christmas carols, and education texts called huehuetlatollis in Nahuátl. When I became an adolescent, I recall encountering in a neighbor’s house a set of Biblioteca del Niño Mexicano (The Mexican Child’s Library), a five-volume novelized history of Mexico by Heriberto Frías, a 19th-century author. In my own house I enjoyed hearing about Pooh and Christopher Robin, studying their actions attentively, following the narrative in graphic terms. But I was fully aware that these characters didn’t have much to do with my immediate surroundings.

Nor, to be honest, would I have had much to relate to in the fairy tales my mother told us, were it not for her ingenuity. What I most remember about the bedtime sessions was her revamping of the conventional plotlines, infusing them with a Jewish component and setting them in a landscape that included elements I could relate to. That act—and art—of reshaping the material emphasized the message she wanted to deliver. The types of trees we had in the front yard, one of which had Mexican jumping beans, showed up in a retelling she did of “Jack and the Beanstalk.” I loved knowing that the same trees I climbed were part of the plot. And I enjoyed it all the more when my mother changed the title character from Jack to Shimele, the name of a friend of mine in Yiddish school. Or else, the three pigs, alone in their respective houses after having been sent out into the threatening world by their mother, were at the mercy of a threatening goy: the wolf. Only Mordecai, the smart pig, capable of solidly building his house with bricks, was able to look adversity in the eye.

As I look back at my mother’s approach, I realize it was as much storytelling as it was midrash. And I’m tempted to think that at its core that is what the Jewish contribution to the tradition of the picture book is about. I’m sure parents everywhere, regardless of their heritage, do the same. But to me my mother’s intrusion into the plot, her restlessness, her desire to appropriate the material is a Jewish quality. The bare bones of an old nursery tale (“Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Three Little Pigs” were first printed in the 19th century, although their roots go deeper into the past) were offered by her through the prism of a biased, targeted interpretation. My mother’s parents were Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Central Europe and, thus, she grew up knowing everything about the vulnerability of being the member of a minority in a largely Catholic mestizo society. Storytelling was a way to insert her Jewish identity and ours into a foreign, often threatening universe.

How often did my mother repeat a particular tale? Dozens of occasions, maybe more. Yet I was enthralled every time she retold it, as if I had never heard the story before. Today I’m bemused— maybe even slightly annoyed—by the number of times my two children, Joshua and Isaiah, have seen the same movie: The Princess Bride, for instance. I ask them if they ever get tired of it. Their response is a smirk, as if saying: you, Dad, don’t understand the pleasures of repetition. Truth is they are right: as an adult I often forget those pleasures, thinking that, as the song argues, repetition kills you.

Knowledge at an early age comes from repetition. To repeat is to allow the pupil to digest. And repetition comes in many forms. Not only did my mother repeat her stories to us at night. As she did it, she slightly modified the material, giving it a subtle yet surprising twist, one we didn’t expect and, thus, felt thrilled to recognize. By doing so, she kept the plot lines fresh. She made it clear that, just as Heraclitus said that no one can enter the same river twice, you can’t hear the exact same tale again: the teller has changed, and so has the listener. Needless to say, the ritual of parents and children bonding around a story is present in numerous cultures. Researchers know that storytelling at home is an essential teaching tool in the development of the child’s intellectual formation. The tale is a conduit through which the child learns a moral code, a mode of behavior, and, all in all, how the world works. Personally, I trace my passion for literature to those early experiences listening to my mother.

Having grown up listening to my mother’s daring retellings, I found books when I was six or seven. I really didn’t like these portable items filled with words. I was a slow reader. Or better, I was an apathetic reader. Perhaps what I most resented was the change from my mother’s melodious storytelling to an activity where my imagination was equally active but which involved more effort on my part. I remember loving a book about an abandoned automobile that a couple of kids in the British countryside decide to repair, ultimately bringing joy to their father, who drives them to a picnic in it. Mexico City at the time was already an overpopulated metropolis, filled with cars. But it wasn’t until I read that book—Un Automóvil Llamado Julia (A Car Called Julia)—that I paid attention to the fact that the mode of transportation I used every day could also have an emotional value. I became conscious then that children in other parts of the world lived in habitats altogether different from mine because the protagonists in that book, a brother and a sister roughly my age, lived in a town with dirt roads and lots of sheep.

It took me some years to discover the value of books. I realized I didn’t need to wait for my mother to be ready at nighttime. I could do it on my own. There was a sense of privacy in the act of reading that I appreciated almost immediately. I was on my own, able to reread a page, to study a picture as long as I needed. What I missed in improvisation—my mother offering a scene I knew well from a different perspective—I gained in multiplicity: I could read not one but four, maybe even six, children’s stories on my own. I could suspend the reading at any point and then pick up where I had left off. In other words, as a reader I was in control.

Again, it is unfortunate that almost none of those books addressed the Jewish elements I was surrounded with, but this is to have been expected since Mexico at the time had a population of thirty-five million. The number of Jews was minuscule: approximately thirty-five thousand. There was little incentive in producing locally-made books about Jewish topics. It was years later, already a grownup (what a terrible state that sometime is, filled with an unavoidable awareness of the blissfulness of childhood!), that I became acquainted with—and came to appreciate in full—the plentiful shelf of Jewish picture books available in English, one that grows handsomely every year. I myself had become by then an immigrant, having left Mexico City in my twenties for New York in search of a milieu where I could explore the labyrinthine paths of the Jewish self the way my mother had taught me.

Not have set out to find anything new, I encountered it the Jewish picture book tradition at a public library, from artists like Maurice Sendak and William Steig to Mark Powdal and the dynamic couple of H. A. and Margaret Rey. Some of their books were explicitly Jewish while others were not, and that, in my view, was enthralling: a Jewish sensibility was to be found in all of them even when their material dealt with other themes. I was equally fascinated by the efforts of established adult authors—such as Isaac Bashevis Singer—whose energy was devoted to hypnotizing retellings of old Hasidic folktales, like those recreating the mythical town Chelm that is overpopulated with dumb Jews. I remember being mesmerized to such degree by my discovery of Singer’s volume of Stories for Children, which includes sharply-delivered pieces like “Mazel and Schlimazel,” “The Fools of Chelm and the Stupid Carp,” and “The Cat Who Thought She Was a Dog and the Dog Who Thought He Was a Cat,” that I quickly ran to the bookstore to buy myself a copy. Since then I’ve bought maybe a dozen copies more because they tend to disappear from where I place them on the shelf.

Among the things Singer says in an essay that serves as epilogue to the book is that children are the best readers of literature. “No matter how young they are,” he writes, “children are deeply concerned with so-called eternal questions: Who created the world? Who ponder such matters as justice, the purpose of life, the why of suffering. They often find it difficult to make peace with the idea that animals are slaughtered so that man can eat them. They are bewildered and frightened by death. They cannot accept the fact that the strong should rule the weak.” I find much wisdom in Singer’s words. I’m convinced that writing a children’s book is actually harder than writing one for adults because adults often speak in condescending ways to children, as if only adults know what the world is about. My discovery of the Jewish picture books I found in the public library showed me that there was another Talmud available, one so-called learned people seldom pay attention to, for there is astonishing wisdom in this tradition as well as astonishing simplicity.

In any case, my discovery has become a full-fledged passion. Over time, I’ve learned that the Jewish picture books in English I became acquainted with were but a branch—arguably the heftiest one—of the healthy tree whose roots began in the 15th century. Its manifestations are heterogeneous in terms of content and multifaceted when it comes to language. The forerunners might be the small alef-beis primers designed for Jewish kids to memorize the Hebrew letters in Europe before the Haskalah, as the Jewish Enlightenment is known, a period encompassed between the late 18th- and the first half of the 19th century and mostly concentrated in the Pale of Settlement, the region in imperial Russia where Jews were allowed to settle. There were also printed songs accompanied by illustrations and the Majse Buch, a Yiddish book of stories about legendary Jewish heroes, mostly biblical. Many of the stories in it were handed down for generations.

One must keep in mind that for millennia there was in Jewish life a prohibition against images as a strategy to fight idolatry and anthropomorphism, as mentioned in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:3-6). Truth is, there were always strategies around the prohibition. Jews living in Christian societies frequently include human silhouettes, although without faces. In the same vein, there are in existence profiles of 17th-century rabbis and other community leaders. Needless to say, animals make a prominent appearance in medieval and renaissance Jewish art. From the 10th century on, illustrated bibles and prayer books began to appear, as well as secular manuscripts with graphic components in them. Most significant is the emergence of the illustrated Haggadah.

Some examples that have survived date back to 1526, when the famous Prague Haggadah incorporated woodcuts with details of the Passover ritual that included beautiful symbols as well as scenes from the journey of Moses leading the Jews out of Egypt into the desert. Nowadays the modern Seder is filled with a vast array of engaging images juxtaposed with prayer, rabbinical response, as well as commentary and poetic meditation. Today there are Haggadot for all tastes: environmentalists, civil-rights activists, feminists, vegetarians, Zionists, etc. It is easy to see the connection between them and the picture book. The roles of writer and artist are almost equal in importance. Recycling ancient material is done inventively, persuading the reader to recognize the modern overtones of the story. And the creators are aware that the material will come alive only when read aloud in a group.

Unlike the Haggadah, which is meant for both adult and child (“You shall tell it to your son on that day,” Exodus 13:8), the target audience of the Jewish picture book is the child, although the adult is in charge of delivering it. The emphasis on Jewish education we are used to nowadays is a byproduct of the Haskalah. An interest in the scientific study of history and a desire to understand myths, symbols, and legends from ancient times pushed the intellectual elite in the Pale of Settlement to see Jewish children not as passive recipients of information but as active participants in their pedagogical instruction. It nurtured an industry devoted to compiling ancient folktales from oral lore, as the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen had done in Germany and Denmark, respectively.

Among the earliest examples of modern Jewish picture books is Lazar Markovich (aka Lamed, Hebrew for the letter El) Lissitzky’s Chad Gadya, a 1917 retelling of the retribution song iniquitous in the Passover Seder that was done for a Haggadah but, in its conception, acquired a self-sufficient shape that enabled the plot of the goat kid to be followed through text and illustrations. The rise of a cheaper printing press in Czarist Russia that allowed for mixing ink color resulted in the manufacturing of an explosion of political posters, theater programs, and children’s literature. Among those famous for making use of it is non-representation artist Vassily Kandinsky. In Jewish circles, such artistic endeavor was equally attractive. Famous artists and set designers like Marc Chagall explored its limits in children’s books with Jewish topics like A mayse mit a hon. Dos tsigele, using a story by mysticism-driven Yiddish writer Pinkhas Kahanovich, alias Der Nister, best known for his novel The Family Mashber.

Yiddish might well be the most important internal Jewish language ever to emerge, and as such it fostered the Jewish picture book industry more than any other tongue. By internal I mean a diasporic device used by the minority in different settings (Poland, Lithuania, Hungary) to distinguish itself from the mainstream. Ladino was influential, especially in the Ottoman Empire, although, as a result of geographical vicissitudes, it never acquired the influence of der mame loshn. In the mid 19th century, the Yiddish press in Europe was astonishingly universal: almost every classic of world literature (from the Bible to Don Quixote and Spinoza’s Ethics) was translated into it, not to mention the array of novels, essays, travelogues, theater, nonfiction, and scholarly examinations. Although children’s books were also an offshoot of this literary history, they didn’t develop, because most of the technological devices that expedite the process came a couple of decades later. Had the massive mobilization of shtetl dwellers and the Holocaust not taken place, it is possible that an exuberant editorial industry in this area would have become globally significant.

But poverty, anti-Semitism, and, ultimately, the atrocities perpetrated by Hitler and Stalin helped relocate the Jewish zeitgeist from the old world to the new, and the tradition of the Jewish picture book moved along with it, firmly establishing itself in English in the United States. It was after World War II that the Jewish minority became more established, keeping its own identity while having a share of the nation’s mainstream culture. The tradition has flourished in English on this side of the Atlantic because of the democratic values intrinsic in our ethnicity-driven society. The formula has been especially beneficial for American Jews, who, like other ethnic groups, are welcome to be full participants in the culture without ever sacrificing their unique traits. And picture books showcase this balancing act, at once managing to stress, in artful fashion, the Americanness and Jewishness of their audience. I’m convinced that the ideals of tolerance in the United States are especially important. Tolerance was a value during my Mexican childhood. But simultaneously stressing one’s Mexicanness and Jewishness wasn’t something to be done in public. Un judío, a Jew, was a rara avis, a rare bird. There was no apparent benefit in combining, in collective terms, these two sides of a person’s identity.

This cultural extroversion of American Jews makes it possible to create a children’s art that is of the highest quality. Think of Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, one of my all-time favorites: it delves into the terrain of children’s deep fears in a way that is at once beautiful and unexpected. The Brothers Grimm tales palpitate in the background but there’s something utterly original in the delivery of the plot line, even though the text is only ten sentences long. Sendak is an American master: his protagonist, Max, dresses up as a wolf during his adventures with the wild things. In other words, he’s still himself inside while pretending to be a fearful animal on the outside, keeping his identity intact.

Needless to say, the United States, since the late 19th century, has had a love affair with the visual image in all its manifestations, and Jews have been at the forefront of this romance, from Hollywood to television, from the comic-book industry to the graphic novel, and, more recently, the rise of the Internet. Movie producers like Samuel Goldwin and superheroes such as Superman have a distinct Jewish sensibility. The Jewish picture book in the United States makes a business of recycling ancient stories, be they biblical or belonging to other periods in history, especially the Yiddish past, like Uri Shulevitz’s The Travels of Benjamin of Tudela, Mordecai Gerstein’s Sholem’s Treasure, and Simms Taback’s retelling of a Yiddish song he heard in his childhood in Joseph Had a Little Overcoat.

There are tales of monsters and miracles that make the reader revel in the wonders of endurance. And there are contemporary stories about escape, like the episodic Curious George (the Reys were Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany who found a safe haven in Brazil before moving to the United States), or about immigration and acculturation, like Linda Heller’s The Castle on Hester Street, and Rich Michelson’s Grandpa’s Gamble or Too Young For Yiddish. Indeed, it’s arguable that American Jews have consolidated their weltanschauung through Jewish picture books. There are volumes like As Good As Anybody, illustrated by Raul Colon, that deal with race relations. Topics such as these were once anathema in Jewish circles, especially among children. Their appearance has brought along enviable openness.

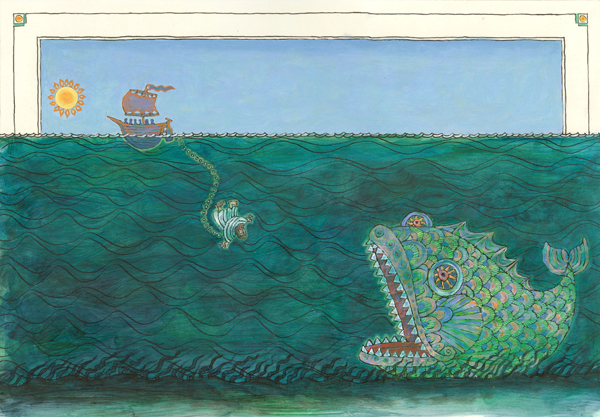

I’ve become particularly interested in the way the Bible has been adapted for Jewish children through picture books. This attitude, needless to say, isn’t particular to the English-language portion of the tradition in the United States. The first children’s Bibles were in Latin during the Middle Ages. The approach, of course, was pedagogical: to nurture the next generation with religious stories from an early age. Aside from the Majse Buch, Jews didn’t embrace it until the 19th century. Books like Moses Mordecai Büdinger’s Derekh Emunah (The Way of Faith) and Jakob Auerbach’s Kleine Schul (Little School) were immensely popular among children. The Bible as a source of inspiration for Jewish picture books in the United States in the second half of the 20th century is fecund, including Singer’s Why Noah Chose the Dove, Mordecai Gerstein’s The White Ram, Jonah and the Two Great Fish, and The Shadow of a Flying Bird, and Elie Wiesel’s King Solomon and his Magic Ring.

Such has been the impetus that books and characters have jumped to other media, as is the case with endless film adaptations, TV shows, and Broadway musicals. And, obviously, numerous titles are regularly made available to audiences worldwide through translations. Given the maturity of the tradition, one might be forgiven for wondering if there was ever a time when such artifacts didn’t exist. So much so that it feels as if American Jews have become the People of the Picture Book. Yet it is nearsighted to believe that only in the United States are artifacts like these, specifically commenting on Jewish motifs, available. In part as a response to translation and the impact of media, but also because globalization works in ways that foster imitations which in turn give room to original items, there are editorial industries, albeit smaller in size, in other nations.

France, for one, has a Jewish picture book tradition defined by figures like Marc Chagall himself. In the Spanish-speaking world, especially in Argentina, authors like Marcelo Birnmajer and Perla Suez have produced books designed for a Jewish audience. In Russia the Jewish writer and children’s literature classic Samuel Marshak generates constant interest. In Brazil, Lasar Segall illustrated Yiddish books, and Moacyr Scliar is responsible for an inspired reimagining of the alef-beis. And in Israel, the number of picture books published on a yearly basis grows as time goes by. I own several different editions of stories by Haim Nakhman Bialik, the poet of the Hebrew renaissance, illustrated for children, as well as dozens of volumes written by contemporary authors. All this is to say that the polyglot and multicultural qualities of the tradition point to its vitality.

I started this appraisal by celebrating the importance my mother’s bedtime tales had on me while suggesting that her enchanting style feels remote as time goes by. I’m not convinced oral storytelling is dead in metropolitan areas. It simply comes in different presentations, as my mother’s exercises prove. Having become a Mexican-American Jew (three identities in one, shifting in kaleidoscopic fashion!), I cherish the astonishing possibilities of the tradition of the Jewish picture book available in English and in other languages. I know that tonight somewhere in the globe a Jewish parent will read a book to a child and in that magical encounter a heritage will magically pass from one generation to the next. But I know that the act of reading is unlikely to be passive.

When my children were little, before tucking them into bed, I frequently read them the Chelm tales from Singer’s Selected for Children that I bought after discovering it in the library. My own reading wasn’t passive. What I enjoyed the most was emulating my mother, deliberately changing parts of the story I came across in the book, setting portions of the plot in our home town, including people my kids and I knew well as characters. At first my children would get annoyed by the intrusion, but in the end that’s what they most appreciated. I wanted the oral and the written to converge in me. For I had learned that reading picture books among Jews is an active, creative endeavor in which the reader controls the tale, becoming a full partner in its authorship.

This article is an abbreviated version of Ilan Stavans’ catalogue essay accompanying the exhibit he co-curated, “Monsters and Miracles: A Journey Through Jewish Picture Books,” at the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles, California, from April 8 to August 1, 2010, moving to the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art and the National Yiddish Book Center, Amherst, Massachusetts, from October 15, 2010 to January 23, 2011.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Ilan Stavans

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats