When Realism Was King: Posters of the Labor Movement

There was a time when Realism ruled. Not one time, actually, but several times, more or less intermittently. The Ash Can Realists of the 1910s, gathered around the Masses magazine (and the social fun of Greenwich Village most of the year, the Cape in the summers), defied nineteenth century American art but also the modernist European abstractions of Picasso and others. Images of working class folks, slum dwellers, kids, but also middle class types in the parks on Sunday: it was a revelation and discovery. Some of America’s most amazing painters, like George Bellows and Stuart Davis, had discovered the emerging America, including urban America and ethnic America, largely hidden as a subject for earlier art.

European avant gardists, going off in other directions, didn’t think much of this American realist work, and neither did the new Museum of Modern Art opening. But Ash Can was not only revolutionary in its time (the Masses was suppressed by Woodrow Wilson’s wartime regime) but also flowed into the folklorist discovery of American vernacular culture, music to poetry, by the likes of Charles Sandburg. It also flowed into the simultaneous discovery of the city (and specifically Greater New York) by African-American, Jewish and other artists and writers of the global metropole. The small flock of skyscrapers looked romantic and the real countryside remained close by, a common vantage point of the age that we often forget now.

Then came the Depression and the Class Struggle. Jewish-American painters, including those who studied in Paris, were onto the subject before it became a subject. Jews had actually been outnumbered among the Masses artists, but the wartime repression and the isolation of the political left to European-American ethnic communities seemed to have marked a dramatic change. Artists like William Gropper (best known for his acid-tipped satirical cartoons aimed at capitalists and bureaucratic labor leaders), avowedly political, but also Hugo Gellert, a former abstractionist who turned to realism, and even modernists like Philip Reisman seemed to discovery the factory and along with it, the bitterness of class oppression. They were joined, soon enough, by a generation faced with the poverty of themselves and their families, along with the terror facing their extended family back in Europe.

Here we step into Agitate! Educate! Organize!, or almost, because the day of the poster was shaped by the Depression but owed much to shifts in the reproduction of art, especially political art. The early 1920s brought the wide use of lithographs, that is, reproductions of high quality bought by art gallery or public art show patrons and passersby; the end of the 1930s brought the high-quality, multicolor poster suitable for massive print runs.

Agitate, organized topically rather than chronologically, contains reproductions mostly from the 1940s and later, a considerable proportion of the post-1970 items created in the Bay Area by people close to the editors of this volume. Inkworks, an independent printshop, scholars Lincoln Cushing, Timothy Drescher and a handful of others, are all very much part of this history, and in a double sense: as historically minded artisan-publishers, researchers, writers and teachers, they have been expert at recuperating old images for new purposes. They have also been very much part of the documentation of labor and radical art history that has been accelerating since the 1970s, despite the ongoing collapse of the labor movement itself.

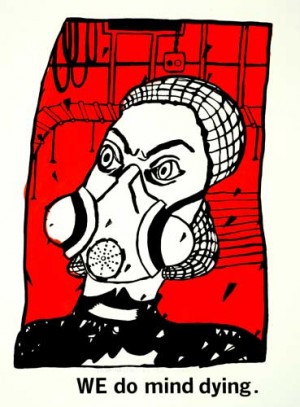

Realism continued into the 1950s era of Abstract Expressionism, aka “Free Enterprise Art” (as Henry Luce called it), although many of the artists were out of work, thanks to McCarthyism, and although many aspects of abstractionism had been tucked into the posters along the way. One of the most curious aspects of this book’s reproductions treats the ways in which LSD-like counter-culture (also based in the Bay Area) styles could be blended with the older styles for the sake of continuing struggles, themselves flavored new issues abroad (solidarity for the Vietnamese, Chileans, Salvadoreans, etc) and by new ways to look at labor struggles (health and safety, Chicano history and farm labor causes, women’s, gay and lesbian efforts, to name only a few).

The accompanying text, written by the editors, is so rich with details as to defy summarization. They could hardly discuss all the images used in the book in any case, but their careful commentary offers insight after insight into process as well as themes of the works. We are unlikely to see any future scholarly study go this far in such detail.

Jewish themes, as such, play no prominent role after 1950, no doubt due to the inclinations of the Jewish artists themselves. A poster for the ILGWU’s “union label” advertising of the 1970s-80s only points up the obvious: industrial work is fleeting union territory and, in the longer run, the United States itself. The labor struggle goes international, as naturally as it would. Posters supporting the Polish Solidarity union movement appear cheek to jowl with posters against NAFTA, and ecological posters for the future of working people (as well as the planet) everywhere.

The main thing, the overarching thing, about this volume is the illustrations themselves, the lush color, the detail, the loving care given to creating something that can be studied by art-lovers and social movement activists but also by future artists, seeking ways to make art and reach ordinary people. Nothing could be more intimately within the tradition of the Jewish radical artist.##

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

- We're on Hiatus!

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?