Review: Seth Tobocman's Understanding the Crash

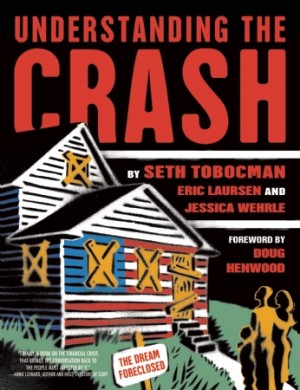

Understanding the Crash. By Seth Tobocman, Eric Laursen and Jesica Wehrle. Soft Scull Press, 128pp, pbk, $15.95.

The information embedded in this visually startling little book will not likely be news to most Zeek readers, even if they have not lived in or near that bottom of the social barrel where the suffering from the Great Recession is worst. But the comic art, the way the comic art works with the text, is likely to be new or at least visually refreshed. Seth Tobocman is a talent of unmistakable originality.

Born in 1958, moved to the Lower East Side during 1978-79 (he soon launched, with fellow Clevelander Peter Kuper, the long-running comic series World War 3 Illustrated), Tobocman simultaneously took up comics and street art, influenced on the one hand by German Expressionism, on the other by the likes of David Wojnarovitz, Richard Hambelton, and Keith Haring. A blocky functionalism that values ideas over atmosphere reflects in his work, now across three decades, an urgency to communicate beyond any existing arts community. His preference for black and white over shades of gray suits a moral and political decisiveness, but also represents an aesthetic disciplined by the characteristic low-tech media of arts activism of the cheap offset newsprint, copy-shop flier and street stencil. These images seem to depend upon solidity rather than fine lines or subtle shades easily lost in production.

Despite this functionalist sensibility, somewhere hidden in this work is another influence, the unlikely stamp of superhero regulars (none of them noted for progressive sentiments, quite the contrary) of Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Jim Steranko. Rather than draw on them for their content, though. Tobocman and all look to these masters at formulae for reducing the body to a set of interlocking geometric shapes, making it possible to draw characters in almost any position without reference to a live model or photo reference, and for practical ways to design a comics page.

Although there is a definite echo of the heroic worker (or impoverished citizen) of once-familiar leftwing agitation in Tobocman’s everyman, especially in his rage against the system, his characters evade such pigeonholes. Reading through Understanding the Crash, looking at the art again and again, reveals the process of Tobocman seeking something for himself in painting, posters and film along with comics, most evident as his indifference to artistic formalism of any kind. Earlier collections, You Don’t Have to Fuck People Over, War in the Neighborhood and Disasters and Resistance: Political Comics, bristle with his militance on all fronts. Likewise here.

Understanding the Crash works best as a forceful and didactic explanation, for the under-20 (perhaps, given the economic illiteracy of the country, under-30) crowd of graphics-oriented Americans, explaining how the housing crisis happened and who is to blame. We follow the history of the late twentieth century as a catastrophe in the making, with banks and assorted investors turning mortgage sales into a casino. Then, somewhat too quickly for the narrative, the industrial base of the country is moved overseas, and the government bails out the very creators of the crisis. The last chapter is given over to how ordinary people are fighting back, and how others can fight back.

Co-scriptwriters Laursen and inker Wehrle have done a fine job, and I think the book will find its needy audience, perhaps through community organizers and others who can pass it (or some of its contents, via the web) on to those who can make it politically useful. Personally, I turn to the art as a comic art, and to Tobocman’s unique contribution. If there is a book to examine in terms of what political art is successor to counterparts of the 1920s-50s (less, I would say, the underground comix phase of the 1960s-70s), this is the book. Read, look again and again–and learn.

#

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

- We're on Hiatus!

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?