Seeking Kafka in Prague

- “And yet – Kafka was Prague and Prague was Kafka…And we his friends…knew that Prague permeated all of Kafka’s writings in the most refined minuscule quantities…” * Jonannes Urzidil in There Goes Kafka

I arrived to Prague in mid-April, yet it felt more like November: cold, gloomy and strangely, emotionally familiar. I had two books in my backpack: The Complete Stories of Franz Kafka and his Letters to Friends, Family and Editors. “Here we are,” I patted my book bag. “After almost forty years, the city you loved to hate.”

I discovered Kafka in the early seventies – and was swept up by the turbulence of his stories – while still in high school in the Soviet Union. I have often wondered why Kafka was ever translated in the bleak and depressing world of Brezhnev’s USSR.

Everything I read in Kafka was about uncertainty and loneliness, futility and repeated failures. It was a world of oppressive reality and bizarre life changes, filled with endless struggle with authority and bureaucracy. I knew this “Kafkaesque” world well: bitter, ironic twists of fate; hopeless situations; alienation; nihilism.

But unlike the characters in Kafka’s stories – my family was able to leave that world behind. In 1989 when the Eastern Bloc communist dictatorship came to an end, the road to Prague – the city that permeated every page of Kafka’s books – was open and we, readers of Kafka for almost four decades, were able to discover his city.

But, as we found, to step into the Prague of Kafka (1883-1924) you have to step into the author’s imagination.

The challenge

There was Kafka in Prague and there is Prague in Kafka – two different entities to understand and navigate. You find very few direct descriptions of Prague settings in his pages, only dispersed fragments of reality in the strangest of contexts. Prague, indirectly and unobtrusively, is forever present in his work.

Prague influenced everything Kafka - as an artist and a man – was. In his diaries and letters, he never stops talking about Prague - its eccentric charm, its medieval streets, its curious legends. Prague is also where Kafka feels condemned to live an essentially unalterable, insecure and futile existence. In his letters, the city is increasingly associated with his existential angst. “I cannot live in Prague…I do not know if I can live anywhere else. But that I cannot live here – that is the least doubtful thing I know,” he writes in the Letter to His Father (1918).

Prague was where Franz Kafka was born, went to school, became a lawyer and worked. But in his writings it was also a timeless metaphor for the kind of life he felt the city forced him to live: a complex web of obstacles and impossibilities that blocked his path at every turn. Kafka wrote of a suffocating and oppressive family environment; of his overpowering father whom he admired but also detested; of the “inescapable anathema” of his double life; his need to write and his job as a lawyer.

Kafka cares little about his readers gaining a concrete image of his city. Instead he gives them ambiguity, supported by illusive perspectives that turned Prague into a visionary symbol that transcended mundane reality.

So, where do you begin to understand Kafka’s relationship with Prague?

End as starting point

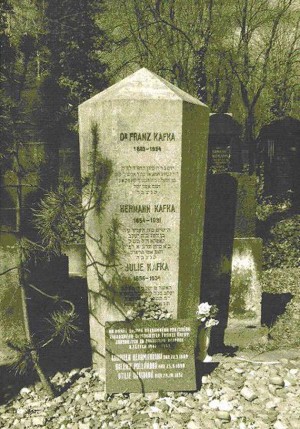

Kafka never escaped Prague. Though he died in a tuberculosis sanatorium near Vienna on June 3, 1924 – one month short of his forty first birthday – his remains were brought back to Prague for burial. His grave is where the journey should start: take Metro Line A to the Zelivskeho Station, then walk to the entrance of the Jewish section (Novy Zidovske hrbitovy) of Strasnice Cemetery. The Kafka family plot is about 600 feet to the right of the entrance.

A family tombstone – in Czech cubism style – marks the plot: father Hermann joined his son in 1931; and his mother, Julie - in 1934. In death, as in their anguished lives, all three are together. The small tablet at the gravesite commemorates Kafka’s sisters. All three perished in Holocaust. On the wall opposite the grave a simple plague recalls Kafka’s lifelong friend Max Brod who, in spite of Kafka’s wishes, published most of his manuscripts posthumously.

Writing was a very personal process for Kafka. Whether he was published or how many read him, was never his concern. “Writing is a form of prayer. Even if no redemption comes, I still want to be worthy of it every moment” (There Goes Kafka). Without Max Brod, Kafka would probably have remained unknown, read only by the few German-speaking intellectuals in Prague and Berlin.

Kafka’s recognition as one of the greatest writers of the 20th Century began after his death, but the Soviet Union’s dominance of the Eastern Bloc countries after World War II forced his works underground. After the “velvet revolution” in Prague in 1989, he became Prague’s favorite son, a saint, martyr, god of modernism – and a prime tourist attraction. Now, however, hardly a single US-published guidebook mentions Kafka.

Today, finding Kafka in Prague is a personal journey of discovery.

Kafka’s Prague as a small circle: Old Town

Once, looking out from his room in Old Town Square, Kafka said to his friend Friedrich Thieberger: “Here was my secondary school, over there…the university and a little further to the left, my office.” Then, he drew a small circle in the air with his finger and added, “My whole life is confined within this small circle” (There Goes Kafka).

In the center of the Old Town Square (Staromestske Namesti) is the massive monument to Jan Hus, a university professor and a preacher, who predated the Protestant Reformation by a century and was burned at stake for heresy in 1415. In 1915, Kafka most surely witnessed the unveiling of the monument in commemoration of the 500 year-anniversary of Hus’ death. He might have been amused by an ironic (Kafkaesque?) twist of history: a monument to the greatest of Protestants peacefully coexisted with the St. Mary’s Column, a symbol of the Counter-Reformation, placed near the center of the Square. In 1918, an anti-Catholic (anti-Habsburgs) mob pulled the column down. Today it stands humbly behind the Tyn Church on the same square.

This was Kafka’s world. The architectural landmarks of the Old Town Square - the gothic Tyn Church where Hus preached; Old Town Hall with its Apostle Clock (which has a chilling stereotypical medieval Jewish money lender among its grotesque figurines); the Kinsky Palace where Kafka went to secondary school, and where his father later owned a shop – all these comprised the contents of Kafka’s “confined…small circle.”

The house where Kafka was born on July 3, 1883 was located on the north-east side of the square, near the baroque Church of St. Nicholas, right at the edge of the Jewish Ghetto. The house burned down at the end of the 1880s and was rebuilt retaining the original portal. In 1965, in the atmosphere of the approaching “Prague Spring” of 1968, a memorial plague with Kafka’s bust was mounted next to the portal: Communist bureaucrats were beginning to grudgingly acknowledge the writer as a critic of bourgeois alienation.

During Kafka’s early childhood, his family lived in a 17th-century house – called the House of the Minute (Minuta) with beautiful Italian Renaissance-style sgraffito frescos on biblical and classical themes – located next to the Old Town Hall. From this house, little Franz, accompanied by the family’s Czech cook, walked to the elementary school that Kafka described years later as “horror.”

Hermann Kafka sent Franz to the Imperial and Royal Old Town German Secondary School in the Kinsky Palace (Palac Golz-Kinskych). Kafka’s experience there was far better than at elementary school: among his classmates was Max Brod, who became his lifelong friend. Just before the start of World War I, Hermann Kafka moved his thriving haberdashery business to the ground floor of the same building.

In February of 1948, from the balcony of the Kinsky Palace, communist Prime Minister Klement Gottwald proclaimed the birth of Communist Czechoslovakia. Now, this pleasant Rococo building houses a collection of paintings from the National Gallery, and a bookstore is located where Hermann Kafka’s business used to be.

Not far from Old Town Square, on Zelezna Street stands the Carolinium building of the Charles University, where Kafka studied and received his doctor of law degree in 1906. One of the oldest universities in Europe, it was founded in 1348 by Charles IV, King of Bohemia and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a university-educated Jew, who did not want to be baptized in order to have a career in the civil service, could choose from only two professions: medicine or law. Pressured by his father into choosing law, Kafka compared his legal studies to being fed with “sawdust that had already been chewed by a thousand mouths.”

Old Town, the seedbed for Kafka’s internal anxieties and conflicts, encompassed also his very special historical circumstances. At the time of his birth, Prague was a capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia and part of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire; when he died he was a citizen of the new Chezhoclovak Republic. He was a Prague-born Jew, yet he spoke and wrote in German. In some of his letters, Kafka described the events he witnessed as a German-speaking Jew in the newly independent republic: the growth of nationalism, workers’ demonstrations, attacks on German-speakers and the destruction of archives in the Jewish Town Hall in the Jewish Ghetto. “I now walk along the streets, and bathe in anti-Semitism,” he wrote in 1920.

Jewish Quarter (Josephof) and Jewish identity

Kafka’s identification with his Jewish heritage was very complex and Jews are conspicuously absent in his writing. In his late twenties, Kafka’s interest toward his roots was sparked when he happened to see the performances of an impoverished Yiddish theatrical troop from Poland. Kafka befriended the group’s lead actor, Yitzchak Lowy, and - trying to promote what the intellectual Prague Jews considered lowbrow culture – he introduced a lecture evening held by Lowy in the Jewish Town Hall in 1912. Thirty years later, Lowy died in Auschwitz.

The Jewish Town Hall can be visited today as part of the Jewish Museum complex in Prague (Zidovske Muzeum Praha). This area, home to several synagogues and the ancient Jewish cemetery, is called Josephof and is the largest and best preserved Jewish quarter in Europe. Josephof owes its survival to the crazy whim of Hitler: he planned to establish a museum of Jews as a degenerate and extinct race, a truly Kafkaesque twist of history.

Kafka’s family was not truly observant and in the Letter to His Father, Kafka blamed him for turning Judaism into a “mere trifle, a joke….You went to the temple four days a year, where you were…closer to the indifferent than to those who took it seriously.”

The Kafkas actually attended two temples in the Jewish Quarter: the Old-New Synagogue and the Pinchus Synagogue: both are now within the Jewish Museum complex. The Old-New Synagogue was built in the 13th century and is the oldest still-functioning Jewish house of worship in Europe. This synagogue, shrouded in the peculiar Prague-style mystery embodied in Kafka’s writing, is linked to one of the most famous Czech Jews: 17th Century Rabbi Jehudah Loew, who is said to be the creator of the Golem, a clay-made artificial being who possessed supernatural powers and protected the city’s Jews against acts of violence. The works of many writers – including Mary Shelly, Karel Capek and Terry Pratchett – have been influenced by the creature. Legend says the Golem’s remains are hidden in the Old-New Synagogue; the rabbi himself is buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery.

In Gustav Janovich’s Conversations with Kafka, Kafka mentioned one day passing by the Old-New Synagogue: “[It] already lies below ground level. But men will go further. They will try to grind the synagogue to dust by destroying the Jews themselves.”

The Pinchus Synagogue, second oldest in the Jewish Quarter, dates from the 16th century. After World War II, it was dedicated to the 80,000 Czech Jews who perished in the Holocaust: their names and those of the concentration camps where they were killed are written on the walls inside the sanctuary.

New Town: “the anathema of double life”

Near the Powder Tower, where Kafka and Max Brod met after work, the Old Town ends and the New Town begins. It was laid out by Charles IV in 1348 as a market center. In Kafka’s time, New Town, with its numerous theaters, discussion societies and coffeehouses, was the very pulse of the unique Czech-German-Austrian-Jewish intellectual synthesis that constituted Kafka’s cultural universe.

Despite Kafka’s tortured perception of his “double life” as a lawyer by day and a writer by night, he was highly respected during his fourteen years (1908-1922) as an analyst of industrial accidents for the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague. It was located at the heart of the New Town, near the Wenceslas Square (Vaclavske Namesti) at No. 7 Na Porici Street. Even though he was well-paid and his work day ended in the early afternoon, Kafka was unhappy. “If one evening my writing has gone well, the next day in the office I burn with impatience and can’t get anything done,” he wrote. “This to-and-fro is getting worse and worse…True hell is here in the office.”

Within Kafka, an artist and a bureaucrat were forced to co-exist and this was his constant tragedy. For him, the bureaucrat he had become was not only an obstacle, he was an enemy. Despite that, Kafka did enjoy and participated in New Town’s numerous cultural attractions, most of which were situated around the Wenceslas Square.

Wenceslas Square, named after the Czechs’ favorite king and saint and with his statue anchoring the square, has always been at the core of not only New Town life but also major events in Czech history. In 1939, Nazi tanks rolled into the Square to signify the conquest of the 21-year-old Czechoslovak Republic. In 1968, “Prague Spring” was crushed there by Soviet tanks. A small memorial commemorates Jan Palach, who in 1969 burned himself to death on the Square to protest Communist oppression. And, in 1989, the independence of the new democratic country was celebrated there.

At the beautiful Art Nouveau Grand Hotel Europa, known to Kafka as the Hotel Erzherzog Stefan, in 1912, he had one of his first public readings. Kafka read from his story The Judgment where a young character’s conflict with his father ends when the old man sentences his own son to death by drowning. Across from the Hotel Europa is the Lucerna, where Kafka and his friends enjoyed cabaret-style performances and movies.

The Cathedral Quarter and the City: Prague in Kafka

Prague had always been the intellectual space that sustained Kafka’s writing. The Cathedral Quarter – a domineering, intimidating area situated across the river from the Old Town – is the best place and space to come closest to understanding the city’s impact on Kafka’s writing.

During the First World War, Kafka used as a retreat the tiny house his sister Ottla rented for him in the Golden Lane, home of the medieval alchemists on Prague Castle (Hradcany) grounds. The little blue house at No. 22 Zlata ulicka is now a Kafka bookstore. This ancient corner of Prague still feels perpetuated with mystery and mysticism. Standing there, in spite of the crowds passing by, you might start thinking about Kafka’s stories and sink into his universe.

It is often assumed the castle in The Castle is Prague Castle or that one chapter from The Trial takes place in the St. Vitus Cathedral located within the courtyard of the Castle grounds. There is no certainty in that and probably that does not matter: Prague landmarks illuminate the inner truth of Kafka’s stories.

And one of the best places to see that is the Kafka Museum. To get there, go from the Castle Quarter through the Small Quarter (Mala Strana) toward the Charles Bridge till you arrive at No. 2b Cihelna, where this unique museum – one of the best conceptual museums I’ve ever visited – is located.

The exhibit opened in Barcelona in 1999, was transferred to the Jewish Museum in New York in 2002, and in 2005 it moved to its true home: Prague. As Mr. Tomáš Kašička, Museum Curator explained to me, the move to Prague was mostly sponsored by a private company COPA.

This is not your usual literary exhibition, where chronologically-organized artifacts, photographs and documents in glass-enclosed cases present visitors with “the facts.” Instead, you encounter a metaphoric reflection of Kafka’s work and life: the words, the images, the light and sound are used to immerse you in Kafka’s imagination.

The exhibit called the “City of K.” is in two parts: Existential Space and Imaginary Topography. The former presents Kafka’s life and the influence the environment he lived in had on him; the later illustrates the transformation of real Prague into Kafka’s Prague. Mr. Kašička has sent me an impressive list of organizations and collections that provided their artifacts and materials for the “City of K”: from the National Film Archive, the Museum of Czech Literature and the Jewish Museum in Prague to the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. and the YIVI Institute for Jewish Research in New York.

In front of the Kafka museum is a life-size sculpture by David Cerny, a well-known and controversial Czech artist: two male figures urinating at each other while standing on the edge of basin resembling the outline of the Czech Republic. These two guys pee with a purpose, however: they do quotes by request. (A nearby plaque explains how to use a phone to make “requests” to spell out just about anything.)

Mentally wired for some Kafkaesque connection, I was looking for this sculpture’s some post-modern allusion to Kafka. Until Mr. Tomáš Kašička told me to relax my “Kafkaesque” grip: The Peeing Men” sculpture was installed in the square well before the museum was established!

On that lovely, sunny, truly April day Kafka’s Prague was laughing at me.

#

Author’s Note: I would like to give my sincere and heartfelt thanks to Mr. Tomáš Kašička, Kafka Museum Curator, for his help with information about the museum, exhibit and the “Pissing Men.”

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?