Felix Nussbaum in Paris

This article is from the ZEEK archive. It originally ran on December 14, 2010.

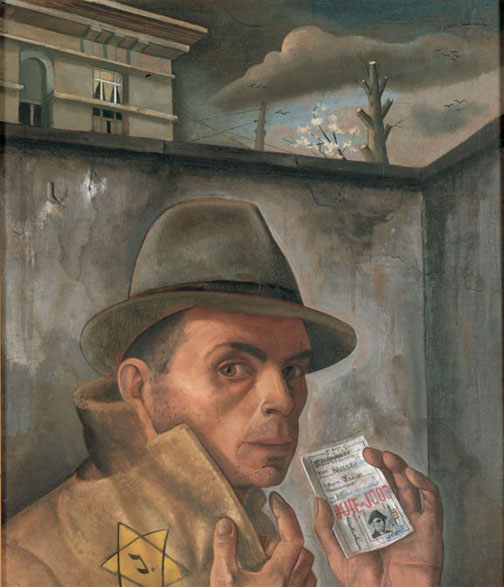

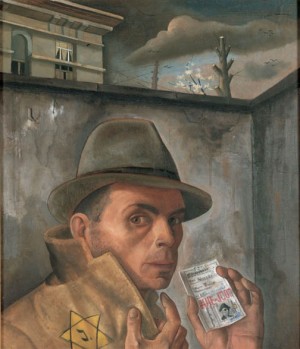

Felix Nussbaum (1904-1944) made a chilling picture in 1943: Self-Portrait with Jewish Passport. He wears a stylish felt hat and a camel’s hair coat to which is plastered a repulsive, mustard-colored star of David raggedly outlined in black. One hand, stretching up like fingers reaching out of hell on a medieval church, hovers at his lapel and throat, an anxious iteration of his body’s being. His other hand displays an identity card snarling: JUIF-JOOD in dumb, red letters.

This portrait is Nussbaum’s legacy; it is defined and possessed by the Holocaust, by Nussbaum’s murder in Auschwitz. His end has defined his entire life, every single thing he did and felt. This interpretive injustice—what we might call, pessimism about the past—this un-history, the Holocaust’s retrospective hold on our past, represents a heart-wrenching, monumental failure of imagination. We leave the murdered where they are, praying they will be still and that we won’t have to think about the Before, the What If…. There was no before.

Scholars have in fact stepped behind the Holocaust in recent years. They have found and shown us life in the shtetl before the roundups: raucous conversation, delicious food, jokes, eyes bright with desire, and yes also the daily sorrows and anguish that is, pace Freud, simply life. We now remember that in cities like Vienna, Czernowitz and Berlin, Jews wrote novels and poetry, sipped their afternoon coffees while relishing cakes and witty conversation, adjudicated in courtrooms, and designed gorgeous houses. And let’s hand it to Philip Roth, who before such studies made headway in the academy, wrote Operation Shylock. Okay, he couldn’t make the Holocaust go away, but his protagonist, a Mr. Roth, could try to talk all the Polish Jews who were left to go back, live again in a place where they had flourished and their Yiddish culture had soared. Why leave Poland to the Goyim? asked this Mr. Roth who looked an awful lot like the writer, Philip.

Even as half the star of David slips out of Nussbaum’s Self-Portrait with Jewish Passport, it hooks us, nauseates us, but we needn’t slink off in despair. Wander up the picture a bit and you find Nussbaum’s gaze, fearful and dismayed to be sure, but not defeated, not a death-mask. All his life pulses in his eyes—his hopes, his tenderness and hesitation, his disbelief, and of course, his distrust. There’s a stand-off in this painting between our poor, dear, desecrated emblem and Nussbaum’s refusal to die.

Artists like Charlotte Salomon and Felix Nussbaum were neurotic, yes, and murdered, yes, but so much thickly else. If we place Nussbaum’s haunted self-portrait with Jewish star amidst his other work and pictures of himself, they tell a story that while ending monstrously thrums with intellectual wonder and artistic magic. Even in Nussbaum’s last works, executed while he was being hunted by informers and the Gestapo, the amazement of being yet, still, complicatedly alive defies his fear and anguish. It’s this stand-off that interests me, between the horror that we know awaits him and his insatiable drive to be. We want to see where life is and was lived in the interstices of recorded and repeated historic events, this reified history of ours. We need to go inside delicately but voraciously, foraging for the heartbeat. The present exhibit of Nussbaum’s paintings at the Jewish Museum in Paris (September 22, 2010-January 23, 2011) is an opportunity to do that.

Felix Nussbaum was born on December 11, 1904 in Osnabruck in northern Germany. His parents, Philipp and Rahel, proprietors of a hardware store, were middle class, assimilated Jews. Philipp, an amateur painter and art collector, encouraged his son’s ambition to be an artist, and introduced him to local painters. For his part, Felix in 1926 painted him a hearty “thank-you note”

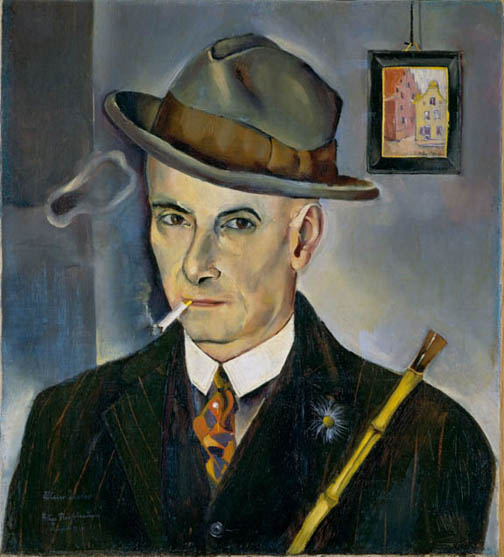

in the form of a portrait in which his father, sporting a tilted grey fedora, a striped suit and flamboyant tie, enjoys what looks like a habitual cigarette as a merry smoke ring climbs ceiling-wards. A bamboo walking stick with yellow amber tip leans against his shoulder, as this pleasure-loving man regards us shrewdly. Behind him to the right is a small painting by his son of a warehouse located in Emden where the father was born and where his family still lives. This portrait, far from being an Oedipally-inflected painting by a 22-year-old of his father, flaunts an avant-gardist confidence. Nussbaum’s style reckons with Max Beckmann, Picasso, de Chirico. He shows himself to be a resourceful, alert and competitive artist.

At 18, he enrolls in art school in Hamburg. At 19 he moves to Berlin and works in the studio of a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, Willy Jaeckel. He meets his future wife, Felka Platek, in that studio where she too is a student. In the same year, 1924, when he is 20, Nussbaum enters the National School of Liberal and Applied Arts. Two years later he has his first one-person show at the Jaques Casper Gallery in Berlin and receives critical attention. The following year, 1928, he takes part in several group exhibitions in Berlin in two different galleries. In 1929 he participates in group shows in Osnabruck, Dusseldorf, Hamburg, Cassel and Berlin again. He continues his studies in Belgium and takes a trip to Arles. He, like his father, is a great admirer of Van Gogh. In the winter of 1932-1933 in recognition of Nussbaum’s work, the Prussian Academy gives him the opportunity to work in Rome at the Villa Massimo. He is 28 years old. At the end of 1933 he travels several times to Paris. Nussbaum did everything an ambitious, talented young artist would do, and he did it well.

Hitler came to power in 1933. Nussbaum’s parents flee Osnabruck for Switzerland, then Italy in 1934 where they see Felix and Felka for what turns out to be the last time. They return to Osnabruck in 1935, sell their store and move to Cologne. In 1937, Nussbaum pere sends his son’s paintings to him in Brussels. In 1939 the parents flee again, this time to Amsterdam where their other son, Justus, and his family have moved. Meanwhile in 1935 Nussbaum and Platek, now permanently exiled, receive authorization to travel in France and decide to request a tourist visa for Belgium. Between 1935 and 1944, the couple, who married in 1937, move from Ostende to Molenbeek-Saint-Jean to Niveze to Spa, to Ostende to Brussels, to Ostende again and finally to Brussels. They renew their visas every six months until they no longer can. Nussbaum is inscribed in the Jewish Register in Brussels on December 24, 1940. In the autumn of 1942 they are denounced by someone they thought to be a friend but who is actually a member of the Gestapo. They escape to the house of friends who at the end of March flee into the Ardennes. The Nussbaums then go back to their old address where their landlord hides them in an attic room where it is impossible to paint; Nussbaum, perhaps Platek too, manage to continue painting in a friend’s basement nearby. They take their lives in their hands every time they leave the attic.

Throughout, Nussbaum continued to exhibit: 1935, a one person show in Cologne and Brussels; 1936, Ostende; 1937, The Hague; 1938, an invitation to participate in a group show in Paris, a response to the “Degenerate Art” exhibit in Munich of July 1937. Nussbaum’s painting kept him alive. I wish I could say the same of Platek, and I wish the Jewish Museum had given us something about her work, even just to say it vanished, if it has.

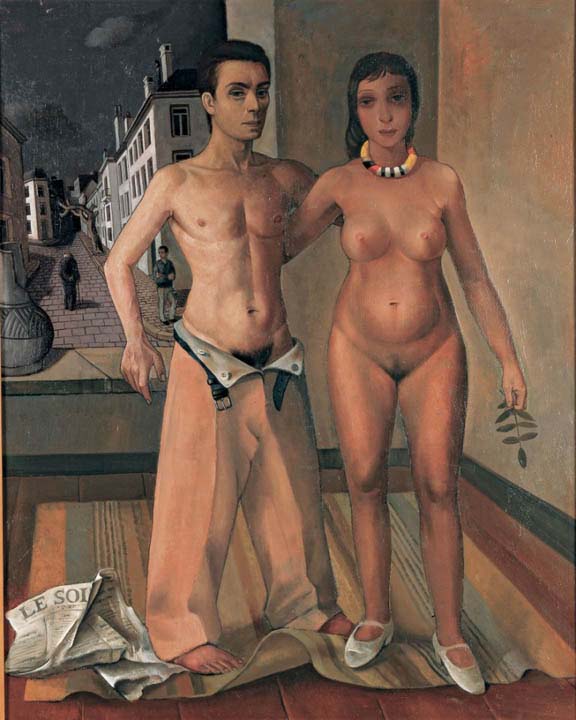

A sign of the couple’s resilience and willfulness —at least in Nussbaum’s mind—is a double portrait he made of them in 1942, their legs planted firmly on the ground, she naked except for a necklace and shoes; he undressed to his groin, his trousers open, belt unbuckled. They challenge danger to find them. I bet they were always like that, she a woman artist and immigrant from Poland, he, a painter wrestling with his personal demons.

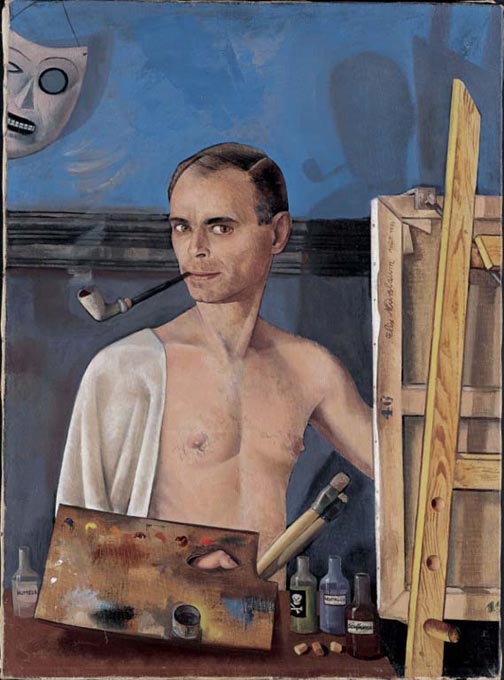

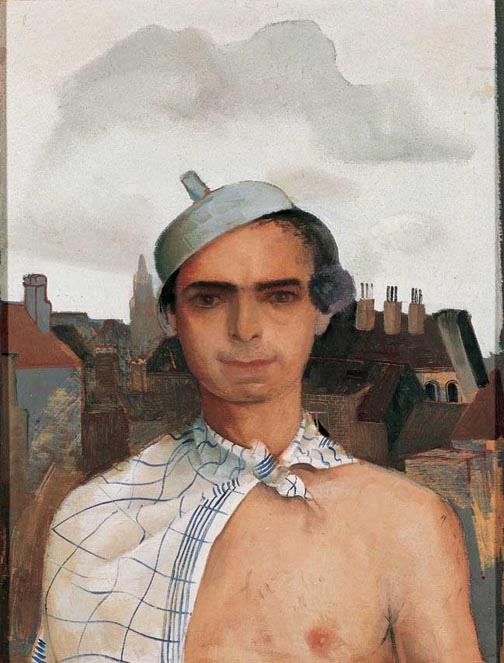

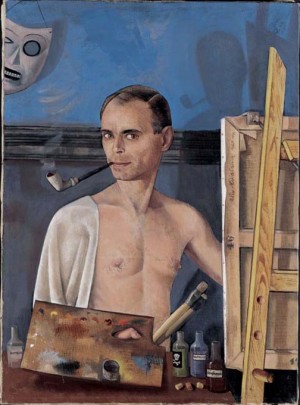

This throbbing persistence, Nussbaum’s daily examination of himself in paint, should be his legacy, not the dejected yellow star in the portrait of 1943. Nussbaum himself never wore the star. In painting after painting, particularly the self-portraits, he lived his life completely. In Self-Portrait of 1928 he wears an elaborate cap while a white mask slips down to almost below his nose. His eyes shift warily. In 1935, Self-Portrait with Chiffon, draped in a mottled white cloth that hugs his neck and shoulder, his head covered by an odd cap, he peers out of a barren cell with gaping black doorway. In Self-Portrait with Dishcloth, 1936, the cap turns into a pot cover, his look as always, mesmerizing, Van Gogh and Picasso sit nearby. A purple flower perched absurdly behind his ear, half his naked chest exposed while the other is covered by a blue and white dishcloth. In the 1943 Self-Portrait at the Easel,

his whole chest is exposed and little wiry black hairs wriggle around his nipples and across his sternum. Again a white cloth hangs over one shoulder. Arrayed before him are four laboratory bottles labeled: “Mood,” “Nostalgia,” “Suffering,” and on one a skull and cross bones. It’s 1943, he’s in hiding in Brussels. This literal specificity sounds a new note. No longer confident of paint alone, he brings in words as he does also the same year in his self-portrait with yellow star.

Unhinging stares, masks and caps and shmatas, naked trees and ankle-high leather shoes—Van Gogh boots—fleeing small dark birds and Nussbaum’s vague exhibitionism—all this fills his work. Dubious, angry, stubborn, there he is, an anxious, competitive artist worrying his way along the trajectory of his life. But history caught up with him, and whatever was personal, familial, masculine, competitive, became the signs of his Jewish tragedy. He was a man struggling with his past and present as an artist, a son, a lover, but Nazism delivered the end of his future. And what is so horribly painful considering Nussbaum’s life is that he was all there before the Holocaust, and everything he was and did was a sign of life. But after he was killed, these qualities were turned into the traits of a victim—signs of desperation and hopelessness, imminent loss, passivity. That is the interpretive injustice I referred to earlier. But he didn’t die, he wasn’t dead, until he was killed. It is his life that one experiences at the Jewish Museum in Paris and why the exhibit is not depressing.

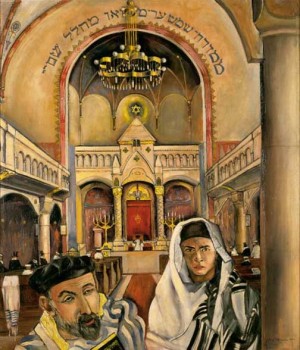

Like so many assimilated Jews in Europe, Nazism turned Nussbaum into a Jew. In 1926, when he painted himself in Two Jews (Interior of the Osnabruck Synagogue), he scowls out of the painting like an adolescent.

If not exactly a pitched battle, the picture represents the young man’s irritation with religious demands. Five years later, in The Painter in the Studio he is still dubious. Dressed in dark trousers, a grey sweater, blue shirt and black tie, he holds a palette. A group of old men, two bearded, two not, draw uncomfortably close to him. All wear long monochromatic black and gray gowns. Head-dresses of similar material cover their heads. Here’s an oddly transvestite and weirdly, almost repulsively religious group. One of the bearded men places a hand on Nussbaum’s shoulder, while the other hand reaches for his palette. The artist restrains the bearded man’s reach. Someone, something, means to hinder the artist. An oversize window opens in the back where a blue moon hovers in a black sky. Here is Van Gogh, and here too, somehow, Judaism: what will his future be as an artist?

In 1925 Nussbaum wrote to his teacher, Ludwig Meidner, also a Jew, wondering about God. He expresses love for his parents and finally says, “Of course painting is perhaps the most important thing to me.” He’s not as forthright as Kafka who claimed he, “almost suffocated from the terrible boredom and pointlessness of the hours in the synagogue.” Nussbaum was just not that interested, or so he thought.

Nussbaum, however, turns out to be a stubbornly Jewish artist indeed. Nearly every time he depicts himself he drapes a scarf, a rag, a dishcloth over his shoulder or around his neck. What is that? A child’s blanky? An artist’s ascot? Or maybe, at least also, a Jew’s tallit. The scarf was there before and after Hitler came to power. And then there’s the ubiquitous cap. Perhaps he wore it to hide his baldness or merely to keep warm. But he needn’t have painted himself wearing it. He put the star of David in his self-portrait, although he never actually wore one. Artists put in their work what they need to and it all adds up to who they are and were. The man with the stick and sack, The Wanderer, frequently makes an appearance in his work as well. Then there’s the barbed wire, that dreadful new Jewish symbol.

Nussbaum was innocent when he first put the cloth and the cap and the Wanderer into his paintings. His life wasn’t threatened. Perhaps unconsciously he was trying to figure out, What is a Jew, what constitutes our identity as Jews without the synagogue and rituals? Perhaps this questioning, these symbols and his searing look, is another reason why his work seems so relevant and alive today.

But Nussbaum was also and inevitably a Christian artist, following Stephen Greenblatt’s so brilliant formulation that we all in the West live Jesus-conditioned lives. Like it or not, Christianity shapes our concepts of God, beauty, work, pride, redemption, usefulness, masculinity, motherliness. And so much more. Nussbaum was an erudite artist and knew to his fingertips the history of Western art which is largely a history of Christian tropes. Take the image of the Wandering Jew, a subject created by Christians to blame Jews for not helping Jesus as he made his way to Calvary—the story of the shoemaker who told him to move on when he lingered with the weight of his cross in front of the cobbler’s shop—and so we were condemned to wander and suffer forever.

In Nussbaum’s The Secret of 1939 the triangular composition is inescapably Christian. In altarpiece after altarpiece it is “God the Father” above, Christ and Mary at either side of him. Sometimes it’s Mary above with Jesus on one side and John the Baptist on the other. The hierarchical disposition of the figures in Nussbaum’s work are iconic, insistent and not anecdotal. Mystery drenches this painting. Gossip and fear chatter and gnaw at the edges; a deep Van Gogh corridor drags us into a place we can’t breath. Silence. Secrets. Suspicion. Drapes, cloths, shmatas. A deeply Christian image reshaped by a hunted Jew and his mad, long-dead Dutch colleague.

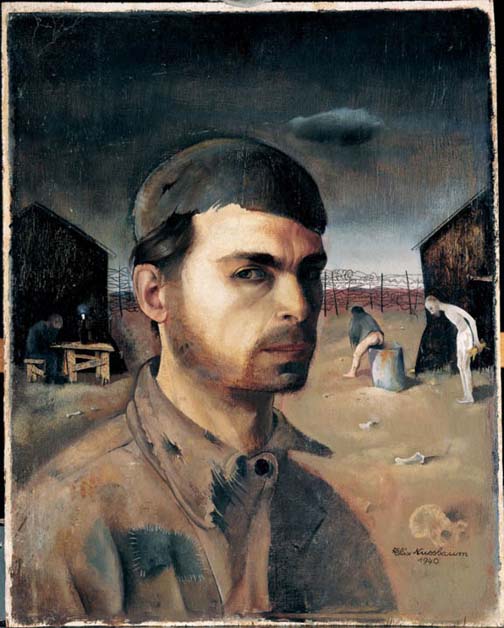

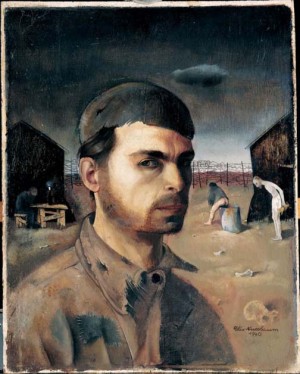

This Christian aspect of Nussbaum’s work is hardest to bear as the end draws near. In His Self-Portrait in the Camp, 1940,

he peers out of an acrid landscape, bearded, shadows under his eyes, hunted, raw, a large flat dark skull-cap—there’s no other name for it—on his head. To his right two nearly naked men move their bowels in plain sight, and carry a bunch of straw to clean themselves. This is hell as only Christian artists like Bosch and Brueghel, and medieval cathedral sculptors know it.

In Prisoners in Saint Cyprien, 1942, Nussbaum paints an almost-Last Supper, men arrayed around wooden boxes and a make-shift, slatted table. He was a prisoner in Saint Cyprien in the Pyrenées in southern France. But worst of all is The Triumph of Death (signed and dated on the back, Felix Nussbaum, April 18, 1944; he and Felka are denounced and arrested on June 20, 1944 and sent July 31 on the last convoy to leave Belgium for Auschwitz). It is inspired by Brueghel’s painting of the same name which in turn was inspired by Bosch. Its ultimate source lies in the Christian conception of the last judgment, the tortures that await those who didn’t follow Christ; think of Stephen Dedalus’ agonies in the last pages of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In Nussbaum’s painting kites shriek in an ashen sky, skeletons roam the land plucking and blowing at musical instruments. Strewn across the front are fragments of sculpture, a sheet of music, a clock and compass, a bulb, chess pieces, a broken typewriter—a horrific premonition of the heaps of eyeglasses, prostheses, shoes left in the antechambers of the gas chambers.

Yet the Jewish Museum in Paris, like the brilliant Felix Nussbaum Haus built by Daniel Libeskind in Osnabruck in 1998, manages to show this doomed man’s work without relegating it to the shadows of his murder. Both the building in Nussbaum’s home town and the exhibit in Paris implicate us in a narrative, that leaves us breathless with fear, shaking with exaltation, astonished by an artist’s drive to live. We are aware of what happened back then during those unspeakable Holocaust years, but we also know, see, taste, revel in what happened before. This in fact is astonishing and contrasts dramatically and unexpectedly to the narrative presented at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where Vincent never escapes his biography and tragic end. So rich in detail and daring in dramaturgy is Paris’ Jewish Museum’s exhibit of Nussbaum’s work that a piece of our history is given back to us, and a door swings open on a hermeneutics and a strategy that defies the conventional story of Jewish victim-hood. It effects nothing less than how we live as Jews, and how we remember.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?