The Listener: Memory, Lies, Art, Power

Holocaust literature must now exceed hundreds of thousands of volumes, the rise of Hitler to power in Germany itself thousands more tomes, but comic art has been selective. Doubtless this is partly because of the recentness of the non-fiction comic or graphic novel, but perhaps also the circumstances suggest so many narrative difficulties. The new book by David Lester, veteran agitational artist based in Vancouver, has something new to add: a microcosm of the historical events that might have foiled Hitler’s rise, but failed to do so.

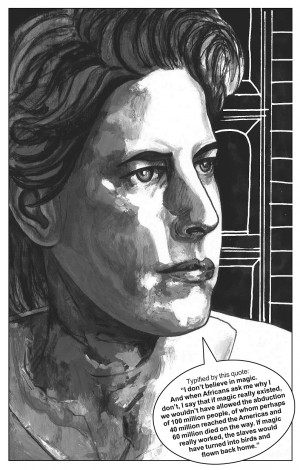

Not that this is all history. The comic begins with a contemporary artist holding a leaflet against Big Pharma and often in the book, past and present are squeezed side-by-side to show us that nothing is stagnant, nothing disconnecting the present from the past…or future. The artist is Louise, in effect the narrator, a radical and visionary who feels great guilt because an activist inspired by her art fell to his death. Not that she has become skeptical of radical resistance, but of herself. The spare quality of the comic art, heavy in grays, emphasizes a grayness in the artist’s life, with an unhappy love affair or two never far from the surface. Biking together through Germany with a new acquaintance/lover, she splits with him and finds herself in a series of European museums, then back in Germany where she meets an elderly woman with a story to tell. Here the historic saga begins to begin, with sketches and an interview of sorts: like the author-artist of the book, the fictional Louise is a good listener.

The small, semi-industrial region of Lippe, almost 90% Lutheran and dominated by conservatives seeking to return to the monarchy and regain the land lost with the Versailles Treaty. Alfred Hugenberg, regional press baron, gets himself elected to parliament and becomes head of the German National Peoples Party, both anti-Nazi and anti-Communist. He is a giant of the film industry as well, owner of the studio UFA that will shortly make The Blue Angel (which in turn will make Marlene Dietrich a global icon).

Hitler is, by this time, approaching his entirely legal seizure of the German nation, but still treading on rather thin ice. Not only are Communist and Socialists–together more than a third of the nation—against him, but so are both liberal bourgeois forces as well as conservatives in the National Peoples Party. In Lippe, the Nazis are challenging traditionalism, the near-feudal power of big landowners over everyone else; their designation as a national but also “socialist” party is an effective guise, and more than that.

Lester shifts back and forth from the accounts of Louise’s conversation, Louise herself, and occasional “documents” like Joseph Goebbels’ meeting with Hitler in the Bavarian Alps in 1932. Then moves to German President Von Hindenburg, who is seeking ways to minimize Hitler’s influence by blunting his advance, breaking Nazi political momentum.

Lester next offers his own break: Louise remembers seeing an issue of the Berkeley Barb (one of the most original of the local underground newspapers) showing the organized, military-style destruction of People’s Park. It inspired her sculpture and continues to prompt her obsession with the purposes of political art. In Lippe, 1932, Hugenburg has declared almost a truce with Hitler; meanwhile, in current time, Louise is still searching, wondering, pondering her lover (who is somewhere else in Europe) and her own artist’s life.

In one of the strongest passages of the book—perhaps one most susceptible to excerpting somewhere—Hitler’s appeal is clearly seen as more than political, an almost mystic force (actually, a carefully manipulated set of images) that make him Germany’s “last hope,” the symbol of a nation with more than a little similarity to the Ronald Reagan “Marlboro Man” restoring virility as well as faith in weary empire America. Germany was in an infinitely worse place, of course, and Hitler had to promise a virtual overthrow of existing capitalism (while preparing to do the opposite: dismantle all resistance to it).

Much of the rest is almost an Afterword, but really a way to express the dilemmas of the artist and of the self-avowed free woman. She has won her freedom at great personal cost, and it often seems that the demands of serious, political art upon her, self-imposed demands of course, are destined to bring her more sadness and fulfillment. (She manifests this metaphorically by wrestling with a clumsy burden, a heavy mirror she is seeking to hang.) Lester frequently poses and reposes the questions of action versus inaction, prompting the reader to ask what s/he should be doing. The film noirish quality of the art itself, obviously inspired by German Expressionism (but also by the work of Ben Shahn and Eric Drooker, among others), constructed through a combination of pencil, pen, watercolor and acrylics, come offas “dark” but also as an urgent appeal.

Louise is an extraordinary original. Speaking as a reviewer of comic art since 1970 and historian of comic art, in some way, for the last thirty years, I can say that no one has captured better this dilemma of the politically-inspired artist. An achievement all the more remarkable because the author-artist of this book has managed to place himself within a female protagonist, with perhaps as much skill as the scriptwriters (one of them, later blacklist victim and my own late friend, Ring Lardner, Jr.) was to manage for his friend, that great actress of spunky women, Katharine Hepburn.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?