Shever v'Tikkun/Shattering and Repair: Lessons from the Journey of Aging

There are many ways of getting ready for a trip, but everyone prepares in some way. Some people are casual, spontaneous. They grab a few items, stuff them in a suitcase, and go at the spur of the moment. Others—my mother, for example—delight in meticulously planning every detail in advance. Still others (including me) are somewhere in the middle. We like to know what to expect, sketch out broad outlines of a plan, and enjoy uncovering possibilities once the trip has begun.

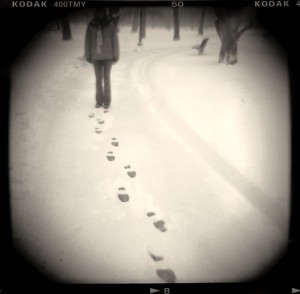

On the journey of life, if we are lucky, all of us will eventually traverse the terrain of aging. Given ever-expanding longevity, we might well be “old” for decades. We’ll certainly be contending with aging long before we are old, as we accompany parents, grandparents, friends, and neighbors through later life. It is strange, therefore, that this profound voyage usually comes upon us as a surprise. In contrast to our varied approaches to traveling, few of us consciously ready ourselves for this path.

Why is this? Contemporary Western culture dreads the challenges of limits, dependency, frailty, and dying. We deny (or camouflage) physical signs of aging. We ghettoize elders in 55-plus communities or institutions. We shape organizations (and even synagogues!) on corporate, cohort-based, segregated models. It is easy to traverse our days and years without getting to know an older person.

I am grateful to have had a different experience. I spent my early adult years in daily contact with older guides; I was the rabbi for a community of 1,100 elders living in a nursing home and supportive-living apartment complex. Accompanying these congregants through illness, loss, learning, celebrating, and, ultimately, the ends of their lives, gave me a precious preview of the journey of life.

Rabbi Isaac Luria, the great mystical sage of 16th century Tzfat, taught that the world we live in, the life we have, is born out of shattering (shevirah). It turns out, through a devastating cosmic accident, that God’s light could not be contained by the “vessels” that God had created to be the world. The vessels shattered.

The light that was abundant and everywhere before creation became hidden and dispersed—encased in shards (klipot) of the vessels that were intended to hold it. The divine is consequently limited and concealed in a world of darkness. Our human task is to find and to liberate those sparks, and thus bring repair (tikkun) and redemption to this broken existence.

I believe this teaching is a worthy template for the journey of later life. In the journey of aging, shatterings are rampant, inevitable, and recurrent. We will all face them.

Shever

Loss of Beloveds We’ll face the shattering of losing dear ones. I will never forget when I was 40 and my dear friend died suddenly and shockingly at the age of 46. A wise but blunt friend offered me very unwelcome words when she said, “Welcome to middle age.” I was outraged, but of course, Margaret was right—as we move through and beyond midlife, we lose our partners, parents, siblings, friends.

Change We’ll meet the shattering of change. Most of us will not work forever; if we have been community volunteers or leaders, there comes a time when we have to voluntarily or involuntarily move aside for those who are coming up behind us. Those of us who are parents see our kids grow up. Our parents grow older and become frail. We are suddenly called to care for them, to guide them, even when they don’t want us to, through complicated and often treacherous choices.

Disillusionment We’ll contend with the shattering of disillusionment. Perhaps we will be crushed by the gap between our youthful idealism and the tenacity of the world’s problems. Or perhaps we will wonder: Is this all there is? My friend told me about a colleague she met at a professional conference. This tenured professor was grieving over the fact that, though she had written three books, none had ever been reviewed in the most prestigious journal in her field. She will never fully meet her expectations and dreams.

Reality We’ll encounter the shattering of the fantasy. We will learn that that we will not always be well, always be independent, always be. Our bodies will change—we will look in the mirror and see a strange person with unexpected wrinkles or gray hair stare back at us. That’s hard, but there will be much harder challenges ahead. Whether it is the subtle loss of name retrieval or the humbling struggle with chronic illness, or the confrontation with disability and dependency, our habituated ways of being will surely be shattered.

In the wake of shattering, the light that was in our lives has been dispersed, and it is hidden—at the moment of cataclysm, we cannot perceive it. To use the language of Luria, the sparks (nitzotzot) are encased in shells or shards (klipot).

When faced with shattering, we feel grief, disgust, fear, anger, abandonment, disappointment, and confusion. Our deepest wish is, “Why can’t it stay the way it was?” We want to return to Eden. We say, “Hasheiveinu, take us back there, God.”

Tikkun

With every shattering, the life we had before is destroyed. Yet we are alive. Our life is thus a new creation—one that emerges out of the shattering. We might wish to go back, but we are not given that choice. The only existential choice is whether we will dwell in the darkness or seek (and lift up) the sparks of light hidden within our new reality. This is what Luria called tikkun.

I’ve seen many older people who cannot get past a shattering, who remain forever immersed in darkness, despair, and bitterness. But I have also seen the ones who reach for the light. I will never forget “Wilma,” whom I met when she entered the nursing home at age 72, after she was paralyzed on one side by a stroke. This woman made everyone her friend, not just her fellow residents, but family members, staff, and even one-time visitors she happened to meet. Wilma was simply a blast to be around. Perhaps most astonishingly, she never forgot a name; once she’d met you, however briefly, she would greet you by name whenever she next saw you.

Wilma had many friends in the home. She was a fixture at Shabbat services, and was a favorite of volunteers who came with their synagogue youth group. When a second stroke left Wilma unable to speak and almost totally paralyzed, it was as if the entire home had been stricken. She was mute, lying flat in bed, and apparently unable to communicate in any way. Unable to swallow, Wilma received nutrition through a feeding tube.

As the weeks went by, visitors noticed that Wilma was trying to tell them things. When a former rabbinic intern returned for a visit, Wilma pointed to the postcard the student had sent to her, which was hung on a bulletin board across the room. Wilma did a lot of pointing and gesturing, much of which was difficult to comprehend. She tried to write, but her handwriting was indecipherable. A speech pathologist provided a board with the alphabet on it, and Wilma would “speak” by pointing to letters that spelled the words she wished to say.

Over time, Wilma returned to synagogue in a reclining wheelchair, and greeted her friends with tears. Robbed of her speech, Wilma was nonetheless eloquent. She looked quite scary, as her face and body were distorted by the strokes, and she was often a tad unkempt, dressed in a housedress and not always modestly covered. If you sat down next to her for even a moment, she would hand you a series of 1940s snapshots of a voluptuous young woman at a Catskill resort, and gesture to let you know that this was Wilma at a younger age. It was as if Wilma figured out a way to say, without a single word being uttered, “Look at me. I may look strange, even frightening. But I was once beautiful. I once made others laugh. There are people who love me.”

I would ask Wilma, “How’s it going?” She would reply with her fingers shaped in the “OK” sign. I would ask if she would be at services, and she would point to the ceiling, her unique sign for “God willing.” And, when I said goodbye, without fail, she would sign, “I love you.”

Wilma was stripped of so many things we count on to make us human: her speech, her ability to eat, her physical attractiveness. Yet, in the face of hardships that would prompt most people to withdraw in anger or frustration, Wilma remained distinctly herself. She found ways to draw others to her with love, creativity, and passion. She sought—and found—the holy sparks and illuminated the darkness for all she touched.

I have dipped into the guidebook for the trip toward later life. Wilma and countless other elders showed me both the terror and the magnificence of growing older. I have learned from them that those of us who are blessed to grow old will be brought face to face with shattering, with darkness, and with sparks of light and the possibility for redemption. No doubt this is true of the whole of life; we cannot ever escape brokenness, loss, limits, and disappointment.

What was it that made Wilma, and so many others who face shattering, able to devote themselves to finding and uncovering the light? Perhaps some people are simply born enlightened, but I believe that we can cultivate spiritual qualities throughout our lives to support us in the work of tikkun. Openness and gratitude, humility and presence are examples. We can work to ground ourselves in that which is enduring, transcendent, and nourishing. We can find tools for this preparation in our tradition—in Torah, avodah (prayer and ritual) and in gemilut hasadim (living in interdependent, caring connection). It takes work and practice to hone a resilient spirit.

Since this path of shevirah and tikkun awaits us all, it can also be immensely valuable to have guides through this terrain. In addition to working on crafting a sustaining spiritual life, I recommend seeking out elders as friends and mentors. Their honest reflections on their struggles and joys, despair and hopes, can point the way for us.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Rabbi Dayle Friedman

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!