Chevra Kaddisha: The Jewish Burial Society

They call me at 8:54 a.m.

“Yes, it would be an honor. Be there in twenty.” I hang up, wring my hands together twice, pull back my hair. I’ve only seen a dead body once before. It was fresh, recently deceased. Nurses carted it away in forty-five minutes.

“I’ll be gone an hour. Chevra Kiddisha called. OK?”

Mother nods. She understands, but told me the other day she wouldn’t have enough guts to walk into the funeral parlor and ritually wash a body she didn’t know. “You’re only seventeen, the youngest one. You can wait a while. Why join Chevra Kiddisha now?” Mother asked last Tuesday. I was on the pottery wheel, spinning my wad of clay around and around, pressing my thumb down into the center. “Because,” I answered, “it is the last thing I can do for this woman. She can’t repay me. I can’t ask for anything back. It’s chesed shel emes—‘the ultimate good deed,’ the last thing I can do before she becomes dust, then dirt, then mud, then the clay in my hand.”

I walk to the door, gear the Volvo, the one with the Flannery O’Connor bumper sticker. When I was fourteen, at the National Storytelling Hall of Fame, I sat by Donald Davis, renowned storyteller, listening to stories of the dead, how in ancient myths ghouls rose from gravestones and ghosts crossed bridges. There were tales after tales. It dawned on me then that everyone, even once they’re six feet under, has a story to be told if people remember.

“You ready?” There are four middle-aged ladies waiting for me in Long’s Funeral Parlor. I recognize them from Synagogue luncheons of lox, bagels, and capers. They are the ones who stay after services to talk to the Rabbi, guide the after-lunch blessing, and take charge of sisterhood dinners. They hand me a laced Kippa, a ritual head covering, as I step into the back room.

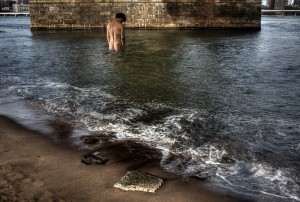

Augusta’s body is on a metal rack. Her sockless feet seem embarrassed, curling under each other, the unclipped toenails flaking with polish. I slip on a glove, tie a paper gown around my waist. I pick up her head, hold it in my palm. Her hair feels like a cotton ball, stretched and expanded. A pink scalp peeps through. Rigor mortis has started to take effect. Her body is limestone.

During the Holocaust, people would die in the cattle cars taking them to the concentration camps. In a car without enough space, children would huddle together as dead bodies turned stone cold and plank hard next to them. Rigor mortis was traumatic there. Gasses would expel. Fluids would drain. And the children would rock back and forth, thumbs in mouth, looking at the body—the woman who used to be their mother. Slowly, I dab egg yolk in Augusta’s mouth and across the chilled facial openings. Her body has been rinsed three times ritually. Her hair has been combed. These steps have been passed down to us from our ancestors for thousands of years.

“Why egg?” I ask. “Rebirth?”

“No, it makes the bugs come, the beetles, helps to decompose the body faster.”

I look down at Augusta, shocked, unsure, imagining worms wiggling out of her nostrils, centipedes creeping from her parted lips. I wonder if she kept a bug farm in a jar when she was a child. I did. I collected six grubs, kept them for a week, studied them under a microscope and fed them apple leaves.

I cup her chin in my hands, speaking to her hollow cheeks. “Augusta, do not worry. I am here for you.” It’s almost as if she can hear me. She wants to tell me her tales. And I am willing to stand there, hold her chilled fingers, murmur a prayer as we weigh down her chest with dirt from Jerusalem, seal her eyes with shards of pottery, set forked olive twigs in her palms.

I had read Augusta’s obituary that morning. It was short. Later today when dusk settles, I will take it in between my fingers and curl my body into a ball, hands crooked over head, and rock back in forth on the carpet. It is difficult to see a body decomposing. It is worse to know its life was condensed into 367 words in the Morning Call, consisting of honors, surviving relatives, and completed duties.

Perhaps it is better to remain unwritten-about than to become lumped into a structured format with the same key words used on Monday, Wednesday, and Sunday. I once wrote my obituary. I taped it to the back of my closet door and stared at it before I got dressed. That was back when I was a reader for the radio for the blind. Every other Saturday, I would cut the obituaries out of the Morning Call and shorten unpronounceable names behind a glass panel door.

The laced Kippa woman in the corner sways from side to side, murmuring Hebrew prayers. It is her official job to keep singing the hymns of our ancestors. She looks up every so often to provide guidance. “The clear nail polish,” she asserts, “must come off.”

I take a cotton swab and gently remove it. I am afraid of death. I am afraid of what will come after it. Sometimes, I think our afterlives will be as described in midrashim, ancient stories the Rabbis tell: After death, we will be seated on rows and rows of wooden stools. They will all look towards the center of the semi-circle. Here in the dimly-lit room, shaped like a Roman gladiator stadium, we will learn Torah for the rest of our spiritual existence. For some of us it will be heaven. For others it will be hell.

Perhaps we will meet angels in the judgment room. I will be terrified of them. According to our legends, they have one foot and six wings. Sometimes, I imagine their eyes are orange peels dipped in mineral oil. Their fingers are long and windy, wrapping around wrists with a tight hold. They will calculate time by the prayers they say each morning and the widows they protect each night.

We clothe Augusta in a cotton dress. It has no pockets. She will not be able to take anything where she goes. There is no lace or frills. Ribbons are absent from the sides. We are all the same in death. There is no rich or poor. Social classes, performance levels, and jobs are social constructions left to the material world. I wonder if Augusta will miss the touch of silk shirts and flannel nightgowns or if she will immediately be reborn into another human being and given another chance at life. I would take that chance if I had it. I would be reborn three times before I’d accept the odds and chance the unknown.

Shanna, my sister, says that death must first feel like hydrogen peroxide on eczema. Eczema was a skin rash she scratched open every night. Her pillow was always speckled with bloodspots. “Don’t touch it,” she’d wince as Mom swathed it in creams. Years later, she’ll go to a Denver hospital to treat it. They’ll cure her in two weeks and fourteen baths. The prescription would be to wear wet pajamas for an hour each day.

But back when she was seven, the doctors came up with a plan. Every night, we followed their directions and pinned Shanna to the bathroom wall. She would squirm and shriek. I would straighten her arms; Mom would pour the liquid on top. Shanna’s cuts would bubble and gush. “Death,” she says, “has the same bone-dry sting.”

I disagree.

I think death is more like fainting. One moment you’re present in the world. The next moment you’re not. But with Augusta in front of me, her body stiff and cold, I almost wish Shanna was right. Perhaps it is better to feel a sharp sting than nothing at all. Tonight, with a felt comforter wrapped around my thighs, I will ponder this and wonder why death in a statistical form feels so abstract. I will think about Rwandan refugee camps, where over 7,000 forgotten refugees died of cholera, a disease easily cured with enough sanitary fluids. In the camps, the ground was rock-hard lava. Refugees were unable to dig to deep for fresh water, and so they drank the contaminated Lake Kira. Decomposing bodies floated periodically to shore, bodies which young children watched but no longer index-finger-pointed. In these camps under makeshift tents, refugees were glazed-eyed-desensitized and rib aching chilled. Until, one by one, they were picked off by cholera and only haunted spirits remained.

Envisioning my own death is an easy task. I will die at age fifty-six in my niece’s converted ambulance, bought for $3,000 and worth $500, adorned with a hand-painted daisy on the back. I will be the driver. Two cousins will be seatbelted side by side with drooped noses and c-section scars. We will be traveling to a family reunion reminiscent of the cousin clubs we all hated in the nineties when our moms forced us in puffed sleeve dresses. But champagne will be available for cheers, and those high-pitch glass clinks can’t be missed. When we hit the antlered deer, to the left of the Pennsylvania pothole road, our vehicle will spin on its side. My forehead will bang into the windshield, and that will be the end. Rigor mortis won’t set in yet. It is only a matter of time.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats