The Nexus of Spirituality and Politics, or, Mitt Romney vs. Exodus 22

Why do some people turn out conservative, and others liberal? What makes one person tilt toward more government assistance for the poor, and another toward rugged individualism? When do we learn to be tough, or be soft?

In an election season, these questions are bracketed for the moment, as politicians scramble to address the concerns voters already have – rather than try to nudge them into new ones. Now is not the time, supposedly, to inquire into root causes. We’ve got an election to win.

But for basically moderate voters sincerely troubled by the sluggish recovery of the last few years, or uninspired by Obama the politician instead of Obama the symbol, how to vote next week may indeed come down to some of those basic principles. Are we helping one another too much, or too little? Should government basically leave us alone, or do each of us owe the weaker among us a duty, with government being the all-too-imperfect means of fulfilling it?

My claim is that the answers to these political questions are not political at all – but ethical, and, for wont of a better word, spiritual. At the end of the day, when moderates pull the lever one way or the other, they are swayed by competing impulses which are not reducible to political commitments, but, rather, precede them. How much do I care? How much do I give?

The Jewish tradition is neither silent nor neutral on these questions. While it is not univocal, it overwhelmingly favors giving more, opening the heart more, and cultivating empathy where it is not naturally found. It understands that all of us are given to selfishness – the great virtue of Ayn Rand, Paul Ryan’s intellectual hero – but unlike Rand and Ryan, moves from selfishness to generosity.

“You shall not mistreat a stranger, nor oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt,” says Exodus 22:21. The baseline here is the acknowledgment of human nature. Left to our own devices, we would indeed mistreat and oppress the stranger, precisely because he is a stranger. All of us feel love for those close to us, like us, in our family or tribe. But morality (of an individual, a nation, or a country) is not measured based upon how we treat those close to us; it is tested on how we treat those unlike us.

In America, that often means the poor, and members of minority groups. It’s all too easy to demonize the 47% of Americans who don’t pay income tax as lazy, or dependent upon government. This is what Reagan said about the “welfare queens” and it’s what Romney said at that notorious fundraiser. Of course, when we look at the details, the picture falls apart: half of that 47% pay payroll tax, many are veterans, many more are seniors.

But if we don’t look at the details – and polls tell us that most Americans don’t – we have to rely on empathy and compassion winning out against selfishness and callousness. For most presumptive readers of this publication, the 47% are strangers. Immigrants are strangers. People who have trouble getting government ID are strangers. It’s natural to say “screw them,” because we never see them.

Exodus 22:21, then, is a spiritual exercise. It demands that each of us, regardless of our individual circumstances, remember or imaginatively remember our shared experience of being a stranger. We are somebody else’s They.

From that remembrance – which in the Jewish tradition is meant to occur every time the liturgy reminds us of how we were once slaves in Egypt; i.e., several times a day, and several more on most of our holidays – springs compassion. And from compassion springs answers to the political questions asked above. If I can really imagine that I might, too, be the stranger, which lever to pull on election day is obvious.

Now, I know that there is some percentage of conservatives who really believe that they are helping the poor by reducing government benefits, and that if we just tax the ultra-rich even less, the benefits will trickle down to everyone. Not every Republican is a denizen of Ayn “The Virtue of Selfishness” Rand. But there are two important responses to would-be compassionate conservatives, one factual, the other ethical.

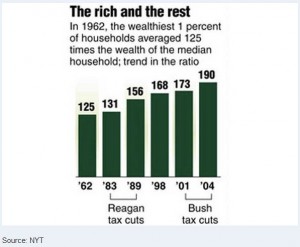

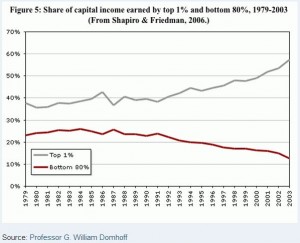

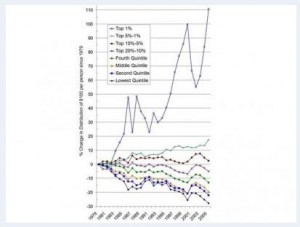

The first is to honestly inquire into the factual question of whether the weakest of our society really do better when the strongest are taxed less. Liberals love answering this question. We are obsessed with graphs and charts which show how the wealth gap has grown over the last twenty years (i.e. the rich are getting much richer) while middle-class and working-poor wages have stagnated. For what it’s worth, I’ve reproduced a couple of these graphs here. They show that the rich have gotten much, much richer, while everyone else has stagnated or gotten worse. In other words, trickle-down economics doesn’t work and never has.

On the contrary, it brought on the great recession. Reducing regulations on financial transactions, allowing huge financial institutions to merge, and concentrating enormous resources at the top of the pyramid all led the top 1% to take on way, way too much risk. And because so much capital was now concentrated in the hands of so few, when those few failed, we all failed.

But the reason such graphs rarely persuade anyone is that the real response to “compassionate conservatism” isn’t data but moral skepticism. Liberals have their charts, conservatives have theirs. We have our economists, they have theirs. Dueling data points make politics look like a courtroom trial, each side with their expert witnesses, and the ultimate decision thus not based on the factual information but rather on a fuzzier sense of which set of experts is more reliable.

In other words, we’re back to where we started: values, ethics, and moral tendencies. If you’re more liberal, you’re inclined to believe liberal graphs; more conservative, more conservative ones.

This is why my second response, the ethical one, is, I think, the most important. If you are a moderate considering voting for Romney, you are required by Jewish values to conduct the following thought experiment. Look inside. When you think of someone powerless, impoverished, unfortunate, what do you feel? Do you feel they must deserve it somehow? Are they “the stranger” to you? Have you, like most of us, had to wall yourself off from feeling too much about such people?

If the answer to any of those questions is yes, you are required by Exodus 22 to not act upon those feelings. They are morally suspect. They are the tendencies we all have, every last one of us, to mistreat the stranger and oppress the poor. Only if you can look one of these individuals in the eye and sincerely feel compassion and care in your heart is it morally permissible to vote for the Republican candidate. You must truly believe that this vote is for their sake, in order for such a vote to be Jewishly defensible. And if there is any evidence in the mind of presumption, or anger, or frustration, you still have more work to do.

This is why Romney’s 47% comment was so important: because it revealed that he does not truly empathize with people he believes are “dependent upon government.” It was instructive

It’s practices like these that make meditation so central to my own spiritual life. Of course, meditation is only one spiritual practice; there’s also prayer, introspection, yoga, philosophical reflection, and a thousand others to choose from. But this is the nexus between spirituality and politics: if you introspect enough, there’s almost no way to harden your heart against the stranger. You just can’t do it.

The prophet Isaiah wrote “God has anointed me to preach good news to the humble, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom to the captive, and liberation to the prisoner.” (Isa. 51:1) The way I understand the phrase ‘God has anointed me’ is that Isaiah’s own spirituality, his own calling, if you will, impels him to preach justice in this way – to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

Most readers of this magazine, and most of our families, are comfortable. Our peril is not falling into abjection but slipping into apathy. We don’t see the stranger often, and when we do, we don’t talk to him or her. We’re not evil; we’re human. This is why religion exists: in order to ensure that we make ethical choices. It doesn’t come naturally; I know, because I myself am so privileged and fortunate, that it is very easy to rationalize my own laziness and self-interest, especially when many people around me are doing the same thing. But it is a moral failing to vote Republican in 2012, when doing so means enriching the rich and failing to help the least fortunate. It is a Jewish failing. It is what our ancestors used to call a sin.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Jay Michaelson

More articles in