From Farm to (Seder) Plate: Supporting a New Crop of Modern-day Isaiahs

Six months ago, my relationship with tomatoes changed forever. Once, they were simply the most delectable part of a salad. Now, I can’t bear to look at one without thinking about the hands that picked it. That’s why there will be a tomato on my family’s Seder plate this Passover. And I won’t be alone. Thousands of Jews across North America will be putting a tomato on their Seder plates, a symbol of the worker who picked it and the campaign to end slavery in the Florida tomato industry. This is our collective way of fulfilling the famous promise found in the Hagaddah, “It is because of what God did for me when I went free from Egypt.”

What happened six months ago? One morning just before daybreak, I found myself huddled with a group of five rabbis in a dimly lit parking lot in Immokalee, FL. Together, we watched as dozens of migrant workers loaded buses for the day. Why? Because the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) had partnered with T’ruah (then Rabbis for Human Rights-North America) to bring a rabbinic delegation to Florida. We came to be inspired by a movement of workers uniting against what one US district attorney called “ground zero for modern slavery.” Together, we listened as these workers described what they are up against and how allies like us — and the communities we represent — can help.

Jessica Shimberg

Rabbi Eric Solomon is one of hundreds of rabbis spreading the word this Passover about how to end sweatshop conditions for tomato workers. He’s pictured here in Southwest Florida , listening to farmworkers talk about what’s happening and how allies can support this growing movement.

This Passover, I look forward to sharing their story, an inspiring one that is having a profound impact. This is the same coalition that created the Fair Food Program, which so far has convinced eleven corporations to only buy tomatoes from farms that follow humane labor practices, and pushed the majority of Florida tomato growers to agree to Fair Food Standards. By signing the Fair Food Agreement, companies submit to audits by a regulatory group empowered to investigate workers’ claims. At the moment, I am happy to report that businesses like Taco Bell, Chipotle, Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s have signed on. That’s a lot of tomatoes, and the Fair Food Program has gotten more than $8 million to workers since the growers signed in 2011. Ongoing campaigns are actively targeting supermarket chains like Publix, Kroger, Stop & Shop, Giant -– and Wendy’s, the only one of the five largest fast food chains not to have signed a Fair Food Agreement. Just this past Sunday, a two-week march across Florida came to a close with 1,500 people standing before Publix headquarters, asking them to join the new day dawning in the tomato industry.

Southwest Florida, home to the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, hosts a slew of tomato and citrus farms employing tens of thousands of mostly Hispanic, Mayan Indian and Haitian immigrants. Workers rise at 4 am, hoping to be chosen by a crew leader for the day. In the thick Gulf Coast heat, they don long sleeves and pants to protect themselves from the sun and skin-burning pesticides. The work is back-breaking: day laborers stand up and crouch down to harvest the best “green-ripe” tomatoes, place them into 32-pound buckets, hoist these onto their shoulders, run to the collection truck and then sprint back to begin again. There’s no time to waste when your family lives in poverty and you earn your wage by the pound.

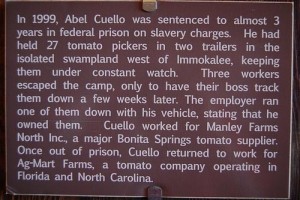

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers formed to protect the legal rights of these ruthlessly overworked and marginalized workers — many of whom do not speak English or know their rights — and to help them stand up for themselves against an agriculture industry that often exploits their vulnerability. In the past ten years, as painfully detailed in Barry Estabrook’s book Tomatoland, the Department of Justice has prosecuted nine cases of slavery in Southwest Florida. Yes, actual slavery where workers were locked in trucks or trailers for the night surrounded by armed guards.

Even more venal, we learned about the everyday crimes far too many farm workers face: physical beatings for not harvesting quickly enough, sexual assaults deep in the fields, and wage theft — the practice of insisting that there is no “record” of an employee’s work. Medical care is nearly non-existent, leaving injured workers in the field waiting until the end of the day. Perhaps most jarring, pregnant workers are exposed so directly to pesticides that they often miscarry or deliver babies with severe birth defects.

Despite seeing evidence of human rights abuses with my own eyes, I didn’t leave Immokalee despairing in my heart. Instead, I felt privileged to meet the modern-day Isaiahs leading the call for farmworker justice. They are not only demanding that tomato farms change their ways or the agriculture industry take notice of its moral blind spot. They are calling for a revolution in how Americans relate to the food that lands on their plates. But, it will take all of us doing our part to make it a reality.

It’s been inspiring to see the Jewish community, led by groups like T’ruah, become involved in the larger food justice movement, one in which Jews are working within the Jewish community to raise awareness while partnering with other faith groups and workers’ groups like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. As a rabbi, it’s particularly meaningful to see the definition of kashrut expand to include food that is truly “fit” to eat, like the Conservative movement’s Magen Tzedek label and the Modern Orthodox Tav HaYosher program, launched by Uri L’Tzedek. The horrific cases of abuse in Postville, Iowa’s kosher slaughterhouses further raised our community’s consciousness to the fact that food may be kosher in the most narrow halakhic sense, but if it is brought to our plates in an immoral way — it must be declared treyf. How can we, for example, recite a blessing over a tomato that was picked by a slave? Our new kashrut standards demand more from us.

This Passover, as we retell the Jewish founding narrative of our exodus from slavery to freedom, I’ll be proud to be one of hundreds of rabbis around the country raising my voice to protect the rights and dignity of tomato workers and let our communities know more about how asking the right questions and making small changes in our consumer behavior can have an enormous impact. Numerous times the Torah reminds us of our slave roots and commands us to honor the stranger for “we were once strangers in the Land of Egypt.” When any other people, but especially those in our own country, are enslaved, it is a Jewish issue.

Trace a few generations back into the family trees of most American Jewish families, and you will likely find an ancestor who immigrated to America and worked in an industry where conditions were similar to those faced by the workers in Immokalee. We, American Jews, will never forget the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and other tragedies that befell workers before New Deal labor protections were enacted. Furthermore, the Torah and rabbinic literature detail numerous halakhot demanding the fair and ethical treatment of workers. Given American Jewish history and our Torah’s commitment to labor justice, we cannot stand idly by while our neighbors bleed in the tomato fields.

A few weeks ago after hearing about my trip to Immokalee, my ten-year old daughter asked our waitress at a local restaurant where they purchased their tomatoes.. A conversation ensued about the Fair Food Campaign that eventually brought in the manager. Imagine if every Jewish consumer asked that question of her local diner.

This Passover, I hope you’ll join me in adding a tomato to your Seder plate. Hopefully, it will lead to a consciousness-raising conversation among your friends and family about the tomato industry, farmworker abuse, and the Campaign for Fair Food. But don’t stop there. A few days later, make a date with your Seder guests to meet at the local supermarket. Find the manager and ask, “Do you know if your store has joined the Fair Food Program, the only proven solution to poverty and modern-day slavery in the Florida tomato industry?” That’s the only way we will make it to the Promised Land of a just agriculture industry, may it happen speedily in our days.

Rabbi Eric Solomon, the spiritual leader of Beth Meyer Synagogue in Raleigh, NC, is a member of T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights and serves on the Social Justice Commission of the Rabbinical Assembly.

Editor’s note: Don’t miss Gal Beckerman’s roundup of justice ideas for your Seder over at the Forward, including another of the many voices calling for justice for tomato workers this Passover.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!