Student Debt-- Education’s Path Spiraling: Time for a Jubilee?

They’re coming again. The plaintive calls. The desperate emails. The pleading Facebook posts. I started reporting on the student loan crisis as a journalist nine years ago, and almost immediately stepped over the line from objective observer to advocate and maven. Friends and friends of friends, acquaintances and relatives of acquaintances, and total strangers pulled me across that line. They started reaching out. They needed help, reassurance, referrals, and sometimes just to know that they weren’t alone.

In my 50s, recovering from a head injury, I haven’t been able to work for years, Sallie Mae wants $65,000…

My daughter is working as a teacher, struggling to pay the bills. She’s supposed to qualify for loan forgiveness, but has been rejected twice…

I’ve already declared bankruptcy, I have no money for a lawyer, is there any way to get my loans forgiven?

My dream is to be a midwife. My parents can’t help me. Should I go back to school? Is it really worth the money?

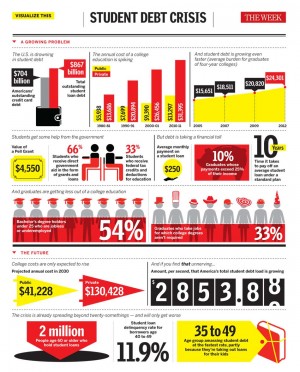

I try to respond as best I can, knowing that in all likelihood it won’t do much. The truth is that the rules of student loans are stacked against people in this country. Two out of three people have to borrow money to pay for college, at tuition rates that increase an average of 5 to 7 percent a year. They graduate with $27,000 in loans on average. Graduate students typically have much higher loan burdens, into the six figures for law school and medical school. Thirteen percent of students default on their loans within three years after graduation.

The inability to keep up with payments has dire consequences, triggering punitive interest rates and penalties that blow up the amount owed to far more than was originally borrowed. There are deferments, forbearances, official government repayment plans that lower the monthly note, but sometimes they’re hard to discover and tedious to apply for. In the vast majority of cases there is no way to get loans fully forgiven, even in bankruptcy. Many borrowers find themselves trudging through a Kafkaesque series of applications and refusals. Many give up and just let the loans pile up hopelessly.

In some ways the hardest questions to answer are those coming from people at the beginning of their educational journeys. These are the hopeful ones, either young or maybe starting a second career, contemplating taking a risk and investing in themselves. They want to do what we, the People of the Book, are always being encouraged to do: study hard, be ambitious, ask good questions, stretch beyond yourself, achieve your dreams.

Education, clearly, is deeply aligned with Jewish values. Particularly in our immigrant culture in the United States, we’ve been encouraged to see education as a means to a material end as well as a good in itself. It worked out that way for my grandfather, who attended pharmacy school on the GI Bill, and for my father who went to Yale on a scholarship and became a professor and poet. It worked out fine for me too, but many in my generation have not been so lucky.

And because we’ve chosen, as a nation, to take education, fundamentally a public good, and recast it into a privately financed investment, I have to be the one to cast shadows of doubt over people’s dreams. Do you love what you’re studying enough to make a life out of it? Are you talented enough to do this kind of work for a living? Will the market pay you fairly for it, even if you succeed? Are you willing to go without owning a home, or starting a family, for as long as it takes to get out from under this debt?

The question of what to do about the problem collectively is in some ways easier. I know this situation can’t go on, and I am hopeful about some of the ways to address it and build the future beyond the current reality of debt for degrees.

When I say it can’t go on, I am not being rhetorical. If you look at the runaway growth of student loans and college tuition over the past three decades, the trend lines suggest an upcoming discontinuity. In other words, the future, in all likelihood, will not resemble the past.

I used to give a presentation in which I showed a graph depicting a famous example of biological overshoot. Reindeer were introduced to the remote St. Matthew Island off the coast of Alaska in the 1960s, where they had plenty to eat and no natural predators. The population grew, and grew, and grew. Then it crashed.

The upward curve on that graph closely tracks that of the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere since 1500; and that of growth of the national debt since 1940; and that of college tuition since 1978; and that of total student loan debt since 1982, which has now crested over $1 trillion. When it comes to both the economy and the ecology, in other words, while the present trends are highly unstable, making a poor basis for predicting the future, it’s safe to assume there’s going to be some kind of correction, and probably not a gentle one.

There is a radical, positive way this might be achieved. Some advocates call for a general amnesty on all debt. This is an idea that goes back to the Bible: that of the Jubilee year. Leviticus 25 lays out the rules for the 50th year, in which fields should lie fallow, poor people who have been forced to sell off their property will be able to return there, and slaves or indentured servants will be freed. A one-time debt jubilee, like a people’s bailout, would act as an enormous boost for exactly the sort of educated people who are supposed to be powering the economy and creating jobs.

On a personal note, I’m putting money away to save for my daughter’s education, but I have no expectation of saving the $360,000 or so it is projected to cost in today’s dollars to send her to four years at a private college. I believe that 15 or 20 years from now, the advances in digitally mediated, self-organized and experiential learning will coalesce into truly high-quality, lower-cost alternatives. I also believe that some proportion of college costs should and will continue to be paid or financed by individuals, but that people will have the option of repaying that money as a proportion of their income. Income-based repayment, which is the policy in Australia and currently being proposed in Oregon, amounts to financing education through a progressive tax, where those who have reaped the largest material rewards from schooling are called upon to pay it forward. And I believe in the idea of a Jubilee, in the sense of some kind of bankruptcy protection on loans. It doesn’t benefit anyone for student debtors to be entirely without redemption.

In other words, I can picture what a brighter future will look like beyond the current student loan crisis. But it doesn’t mean I have a comforting answer for every member of this generation who is worried about his or her personal future. The only thing I can say is that if you are personally affected by student loan debt, consider crossing that line into advocacy. According to your bent, get involved at your synagogue or Hillel, or with policy efforts by groups like Strike Debt, [Student Loan Justice] (http://bit.ly/12URy9I), or Generation Progress. In the end it’s collective solutions that are going to make the real difference.

Anya Kamenetz is the author of Generation Debt, DIY U, and the Edupunks’ Guide, a free resource for independent learners. She’s running a webinar that begins August 7 that will provide more help and actionable information to those affected by student loans. A version of this piece will appear in Evolver.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in