Praying With Our Lips: Another Side of Heschel’s Legacy

At a particularly dark and lonely time in my life, I found myself one afternoon praying on the floor of my living room. I prayed to God, out of sadness and heartbreak, fear and confusion. I prayed for comfort, for strength, for the tortuous feelings of emptiness and loneliness to disappear. At a certain point in my praying, I was overcome by the recognition that I was not alone in my pain, that others around the world, and over the course of time, had suffered similarly, that my experience was not mine alone, but was one of all of humanity. In that moment, something in my prayer shifted. I felt a closeness to all human beings, through time and space, whose hearts had ever ached as my heart ached. I felt the interconnectedness of humanity. And I began to feel compassion for all others who were suffering as I was. My prayer became a prayer for the emotional well-being of others, rather than for the alleviation of my own pain.

I was reminded of this incident earlier this year, when reading through many of Abraham Joshua Heschel’s writings on the nature of prayer. For central to Heschel’s conception of prayer is this refocusing from the experience of the self to the experience of the other. In considering this view of prayer, we find that it is intimately connected to Heschel’s commitment to social activism as a religious act.

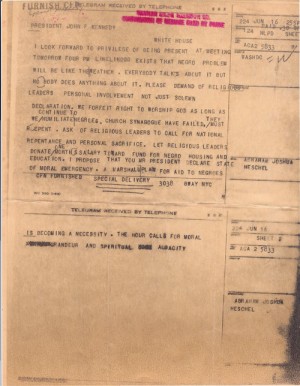

Fifty years ago this past June, President John F. Kennedy organized a convening of religious leaders to discuss civil rights issues in a meeting at the White House. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, among the invited clergy, responded to the president with a telegram that has become famous for its powerfully succinct condemnation of those who failed to act in the face of racial injustice:

I look forward to privilege of being present at meeting tomorrow four pm. Likelihood exists that Negro problem will be like the weather. Everybody talks about it but nobody does anything about it. Please demand of religious leaders personal involvement not just solemn declaration. We forfeit the right to worship God as long as we continue to humiliate Negroes. Church synagogue have failed. They must repent. Ask of religious leaders to call for national repentance and personal sacrifice. Let religious leaders donate one month’s salary toward fund for Negro housing and education. I propose that you Mr. President declare state of moral emergency. A Marshall plan for aid to Negroes is becoming a necessity. The hour calls for moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.

In these brief sentences, Heschel expressed his firm belief that the religious experience of worship could not be divorced from one’s actions outside the ecclesiastical walls; those who failed to act publicly against injustice could lay no claim to the mantle of religiosity.

For many in what has become known as the Jewish social justice field, myself included, Heschel’s words never cease to inspire. His is the voice of the modern-day prophet, echoing the sentiments of Amos, Micah and Isaiah in their critique of religious leaders who silently allowed hunger, poverty, and other forms of suffering to persist in their societies. Frequently cited in these circles is the statement Heschel made following the Selma Civil Rights March in 1965, when he joined with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other religious and political figures in a third — and finally successful — attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery, AL, and demand voting rights for African Americans at the Alabama state capitol:

For many of us the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.

These six words — “I felt my legs were praying” — are a stunningly poetic articulation of the idea that one’s work for social change can be a religious or spiritual expression. Unsurprisingly, this quote has taken on mantra-like status among many Jewish social justice activists.

But to revere Heschel solely for his prophetic insistence on the Jewish community’s participation in social change movements is to overlook the totality of Heschel’s significance as a Jewish leader and thinker. Social justice activists of all religious and spiritual stripes have something to learn from what Heschel understood as the power and practice of praying — not with one’s feet, but with one’s mouth, lips, and words.

The Oxford Dictionary defines prayer as “a solemn request for help or expression of thanks addressed to God or an object of worship,” and I would venture to guess that most people would suggest a similar definition if asked. In this understanding, prayer is an expression of gratitude, desire, or despair born out of one’s own emotional state and needs. The self and its experience motivate the act of praying. But for Heschel, true prayer is something entirely different. His book “Man’s Quest for God,” published in 1954, is his work most focused on the practice of prayer. Throughout the text, he defines prayer as the act of suppressing or forgetting one’s own self and self-interests, and of turning one’s focus to God. He explains that prayer is not in fact an act of self-expression, but rather that

The focus of prayer is not the self. It is the momentary disregard of our personal concerns, the absence of self-centered thoughts, which constitute the act of prayer. Feeling becomes prayer in the moment in which we forget ourselves and become aware of God.

This articulation of prayer as self-forgetting, or self-minimization, calls to mind the Kabbalistic notion of tzimtzum, a word that literally means contraction and that carries mystical connotations referring to the act of divine contraction that allowed space for the creation of the world. For Heschel, the contraction of the self during prayer similarly creates space: space for God, and, as we will see, space for other human beings.

To understand how Heschel might have arrived at such a conception of prayer, we need only briefly acquaint ourselves with the core tenet of his theology, namely, that God is a personal God, a “God In Search of Man” (the title of one of his most well-known works). In this theological framework, God longs for a relationship with humankind, calling out: “Ayeka,” “Where are you?”

Heschel sees prayer as the human response to this call, the medium through which one acknowledges God’s presence in the world and enters into a relationship with the divine. Our ability to enter into this relationship, however, is not automatic; as Heschel makes clear in “Man’s Quest for God,” it is predicated upon our willingness to make ourselves visible to God, stripping ourselves of any pretense and standing spiritually naked, as it were, before the divine presence. Moreover, we can only make ourselves vulnerable and visible before God, if we shift our understanding that we, and our own interests, are not at the center of the universe. In a 1958 address given at Union Theological Seminary on “Prayer and Theological Discipline,” Heschel explicitly united these ideas and the theory behind them, proclaiming that “to disclose the self we must learn how to cast off the shells of ambition, of vanity, of infatuation with success. “

In other words, responding to God through prayer, and disclosing the self in this activity, is impossible if we have not shifted our focus from the self to God, letting go of the notion that our own interests and desires are at the center of the universe. This self-disclosure is in and of itself an act of tzimtzum that creates the space for a relationship with the divine. Thus the theology that underpins Heschel’s conception of prayer — as an act of self-disclosure in response to God’s call — is part of what allows for his unique and somewhat radical idea that prayer is an act of self-contraction, rather than an act of self-expression or self-centeredness.

So what does all this have to do with social justice and public action? The connection becomes clear when we consider that Heschel’s understanding of what it means to respond to injustice is bound up in his foundational belief that the world’s greatest evils are indifference and callousness. He writes that indifference to wonder is “the root of all sin,”while indifference to evil is “even more insidious than evil itself; it is more universal, more contagious, more dangerous.” Whether one is unmoved by the wonders and mysteries of the world, or by the existence of evil in the world, it is this callousness that poses the greatest threat to humanity. Thus one’s ability to become attuned to the suffering of others, and to respond to the suffering through concrete action, is predicated on the absence of indifference, and the creation of space for something other than the self, in one’s own heart and mind. For Heschel, true prayer — constituted by the act of casting aside our own desires and seeing ourselves as but a speck in a larger divine universe — is an act that creates this space for the other in our worldview, opening our hearts to the suffering of others. He writes:

There is a loneliness in us that hears. When the soul parts from the company of the ego and its retinue of petty conceits; when we cease to exploit all things but instead pray the world’s cry, the world’s sigh, our loneliness may hear the living grace beyond all power.

When we pray, the “parting company” of the soul and the ego — namely the tzimtzum that Heschel has described — allows for attunement to others’ pain. As we become more focused on the needs of others, and less focused on ourselves, we begin to pray a new type of prayer, the prayer of the world’s cry and sigh. This prayer, in turn, brings us into even deeper relationship with God as we are able to “hear the living grace beyond all power,” namely, the divine presence.

Ultimately, what Heschel is teaching us is that prayer is “a moment when humility is reality.” When we engage in tzimtzum, and understand that we are not the center of the universe, we stand more humbly before God and others. This humility prepares us to hear the suffering of others and to respond to it through action; even more significantly, Heschel asserts that such humility is a necessary quality for those who desire to act for justice. He reminds us that two biblical figures who are famous for their bold action on behalf of those who were oppressed — Abraham and Moses — spoke out to the powers that be only after an expression of such humility.

Heschel’s legacy to those who are motivated by their Judaism to work for social change, is his teaching that praying with our lips is what makes it possible to then pray with our legs. For Heschel, any response to evil in the world can come only through a humble recognition of one’s own place in the universe — and therefore, as meaningful and important as social activism is, it is by no means a replacement for prayer and ritual. Rather it is impossible to divorce this activity from the practice of prayer, for it is prayer itself that enables one to act. Prayer is the process by which we are both able to break through callousness and indifference and to cultivate the quality of humility in our own beings. True worship is the continued practice of humility, of reminding ourselves of the truth of our own smallness, making it possible for us to be opened to “the world’s cry and world’s sigh.” Through this recognition of our own smallness, we become big enough to act.

Shuli Passow is a Jewish educator and communal professional who most recently served as the director of community initiatives at Jewish Funds for Justice, where she worked with synagogues across the country to support their involvement in congregation-based community organizing. She has taught widely in youth and adult education settings, and is particularly passionate about exploring issues of justice, compassion, environmentalism and economics through Jewish text. Shuli is currently pursuing rabbinic ordination at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

In His Own Words: A Heschel Reading List

“Abraham Joshua Heschel: Essential Writings,” ed. Susannah Heschel. Orbis Books, 2011.

“God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism,” Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1955.

“Man’s Quest for God: Studies in Prayer and Symbolism,” Scribner’s, 1954.

“Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity: Essays,” ed. Susannah Heschel.Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996)

“Prayer and Theological Discipline,” Union Seminary Quarterly Review, Vol XIV No 4, May 1959.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Shuli Passow

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats