Welcoming the (Abortion-Seeking) Stranger: Reflections for a Season of Renewal

“This is Meredith,” the voice on the phone announced one afternoon in March. “We have someone who needs a place to stay for the night.”

I took a deep breath. It was the first time I’d gotten a call from the Haven Coalition since I’d signed up to volunteer. I ran my fingers through my hair as Meredith told me about Pearl: 25 years old, 20 weeks pregnant. She’d arrived in New York City from Buffalo and just finished the first part of a two-day abortion procedure. She would wait for me at the clinic on the Upper West Side.

When I arrived at the medical office four hours later, a few women sat scattered throughout the large waiting room. They flipped through magazines, turning pages so quickly I wondered if their eyes absorbed anything. No one spoke. A TV droned. The lavender chairs added a soft touch of color to the otherwise gray space. I told the guard at the security desk that I was from Haven and looking for a woman named Pearl. He rubbed his bald head and pointed to the far corner, where a young girl sat slumped, staring into space. An oversized black sweatshirt hid her protruding belly. She did not look a day over 16.

“Hey, I’m Suzanne.” Pearl lifted her head, meeting me with dull brown eyes. Her Greyhound bus had departed at 3 am. It was now 6:30 pm. “I’m here to bring you to my apartment for the night.” Saying that felt strangely sleazy, like I was picking her up at a bar. She nodded, and laboriously lifted herself from the chair. Air hissed from the plastic-coated seat cushion.

Outside, Pearl told me that she lived on a Native American reservation. “Dude, I’m the first person in my family to go to college,” she said. “Once I graduate, everything will be different for me.” She was quiet the rest of the short walk.

I paused a few blocks from my apartment. “Want to stop for something to eat, or order food when we get home?”

She looked at the ground, her face obscured by long black hair.

“It’s on me,” I said.

“Cool. Thanks. I haven’t eaten anything all day.”

After dinner, she collapsed on the couch. I went to the gym, returned, went to bed. At 5:45 the next morning I found her in the same position. A quick cab ride later, we stood outside the office building that housed the clinic. We nodded at each other and said good-bye. She shifted her bag, then pulled open the glass door. My part was done. Our paths wouldn’t cross again.

I became involved with Haven in 2005, not long before I met Pearl. In the days after George W. Bush’s second inauguration, news analyses foretold the devastating impact another term would have on the already diminished state of reproductive rights. Eventually I stumbled onto an organization that offered grants to help low-income women pay for abortions, which Medicaid hasn’t covered in 35 states since 1976.

I thought I would feel a little bit better about the condition of the country if I could get involved with a group like that. An Internet investigation led me to the Haven Coalition, which connects women forced to travel to New York City for “late-term” abortions –- at 14- to 24-weeks – with volunteers who provide a meal and a safe place to sleep.

The accommodations are necessary because second-trimester abortions are two-day, outpatient procedures. On the first day, a type of kelp called laminaria is used to begin cervical dilatation; the next morning the abortion is completed. Fewer than 10 percent of abortions in the United States occur after the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

In the rare instances when procedures are performed beyond the first term, reasons vary widely. Some women cannot afford the procedure: By the time they save enough money or find financial assistance, they are in the second trimester. Other women do not completely stop menstruating when they become pregnant, discovering their pregnancies at the end of the first trimester. Some women don’t know where to turn for help. Others find out about severe fetal defects detected by tests administered halfway through the pregnancy. Only two percent of abortions happen after the 21st week.

For women who are more than 14 weeks pregnant, there’s an extra financial burden, since second-trimester abortions are more expensive. And it’s often challenging to find a doctor to perform a second-trimester abortion, making it more likely that women seeking later procedures will need e to travel greater distances because the number of abortion providers drops dramatically with each additional week’s gestation. Researchers at the Guttmacher Institute found that “women obtaining abortions at 16 weeks or later were twice as likely to have traveled 25, 50 or 100 miles or more compared with women seeking first-trimester procedures.”

There are several places in New York City where a woman can obtain a safe abortion up to 24 weeks into her pregnancy. Many women who find their way to New York barely have enough money to pay for travel and the abortions, let alone a hotel room, which averages around $250 per night. Haven was founded in 2001 by a group of activists who discovered that patients traveling to the city for abortions were spending the night on park benches, in their cars, or at Port Authority Bus Terminal.

If one of Haven’s partner clinics had a patient who needed a place to stay, the social worker would call the Haven hotline, staffed by a volunteer. The “phoner” gets a patient’s basic information and calls the volunteer signed up to host that night. The host then picks up the patient (and her companion, if there is one) from the clinic, brings her home, provides her with dinner, and escorts her back to the clinic in the morning. Hosting more than once a month is discouraged; hosts can burn out from too many intimate encounters in a short time. That year, about 100 volunteers hosted over 130 women.

Another call from Haven came in May. Could I accommodate two different patients? Maria was 28 years old and from Peekskill. She spoke only Spanish and was 14 weeks pregnant. Monique hailed from Buffalo. She was 37 years old, 24 weeks pregnant, and already the mother of two. My living room includes two couches. It might be crowded, but we could make it work.

By the time I arrived at the Murray Hill clinic at 6:30, Maria and Monique were the last two people in the waiting room. They’d been at the clinic all day. After checking in, each woman had waited to speak with a social worker, then waited for gynecological exams. Once the laminaria sticks were in place, there was no turning back, as the seaweed insert began its work of dilating the cervix. Maria, I later discovered, was also given a shot of digoxin. The women lumbered out with me, and the security guard locked the door behind us.

It was rush hour, but I thought the fastest way to get home would be to take the uptown 6 train, then transfer to a crosstown bus. As we descended into the subway, I gave MetroCards to Maria and Monique and struggled not to lose them in the bustling crowd. It was the first time either had ridden in a subway. The train was packed, but I made a clearing for Maria and Monique. Warm bodies pressed against us on all sides. Maria’s face had a greenish hue.

As we emerged from underground, Maria grimaced with every step. I scrapped my plan to take the bus and hailed a cab. While we sat in traffic on 79th Street, Maria groaned. Monique and I quietly discussed what could be wrong.

An hour after we left the clinic, the doorman at my building greeted me, eyeing my guests: two pregnant women of color, one moving with great effort. Whatever he thought, he just nodded when I told him two friends were staying with me for the night.

Once inside, the ladies each chose a couch. In broken Spanish, I asked Maria if I should call the clinic, which has a nurse on duty overnight, but she shook her head. Perhaps she feared that she’d have to go to the hospital and they might ask about her immigration status. I handed Monique the TV remote, and she flipped through channels while I ordered dinner.

Monique told me about her two kids. Her son was a senior in high school, planning to go to SUNY Buffalo when he graduated. Her daughter was finishing at a community college. “I called a few hotels before I came,” she said. “Each one was $300 or more. That’s more than my mortgage payment!” She laughed. “But even though I ain’t got no place to stay, I came anyway. My husband and I are done with raising up kids. No way I’m dealing with a teenager when we’re trying to retire.”

Dinner arrived. I immediately regretted my choice. Greasy pizza was not a good option for someone in Maria’s condition. She joined Monique and me at the chipped dining room table and choked down a piece anyway. We returned to the living room and watched TV. No one was surprised when Maria leaned over and puked on the hardwood floor. “Perdone, perdone,” she said. She lay back on the couch and closed her eyes.

“No hay problema,” I replied, using the full extent of my Spanish. I grabbed a roll of paper towels..

“Shit, now I’m gonna be sick,” Monique said. She ran to the bathroom.

I called the clinic. The nurse said that the digoxin made Maria nauseated. She suggested a cold compress. It seemed to help only slightly. At midnight, Monique and Maria were still taking turns vomiting in the toilet.

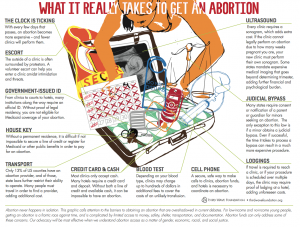

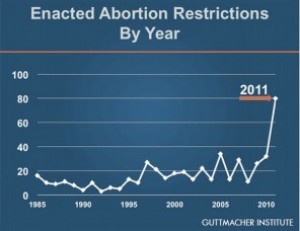

Back in 2005, I thought that it was challenging to access abortion. I joined Haven because the right to choose is meaningless if someone can’t get an abortion when and where she needs one. There are no licensed providers in 87 percent of US counties. State legislators who want to eliminate abortion services pass prohibitive, irrelevant mandates meant to close clinics or drive up the costs until services are almost impossible to provide. In 2011 and 2012, more than 400 abortion restrictions were introduced in state legislatures; over 83 measures passed in 2011 alone, triple the number passed in 2010.

This year has also proved to be a watershed for anti-choice legislation, most famously in Texas, when state Senator Wendy Davis bravely filibustered for 13 hours against a bill that would have lead to the closure of 37 of 42 reproductive health care clinics in the state and banned abortions after 20 weeks. She won temporarily, but the measure was ultimately signed into law.

On top of the scarcity of providers and lack of Medicaid funding, nuances in the language of the Affordable Care Act may cause private insurance plans to drop coverage of abortion services, or force women to pay for separate “abortion riders”. While women with resources will always find a way to safely terminate unwanted pregnancies, poor women suffer disproportionately under this restrictive, hostile environment.

I joined Haven because I am Jewish, and I embrace the tradition of social justice. I wanted to act with ometz, the courage to take risks in pursuing a just cause, and fulfill my obligation of tikkun olam, the call to repair a world rife with inequity.

One member of Haven, Rabbi David Adelson, dedicated a Rosh Hashanah sermon to Haven’s work. He told his congregation that we are created equally in the image of God — b’tselem elohim — and it is our responsibility to ensure that all people are treated equally as well. “Rights are rights only if they apply to all,” he said. “Otherwise they are simply privilege. Our Jewish tradition demands that we disperse privilege evenly, and work to defend the rights of every member of society.” These concepts formed my core beliefs. I could not expect others to do what I myself would not.

In September, I hosted Marianne, 15, and her mother, Soleil. They took the commuter train into the city from Connecticut. Marianne watched the Cartoon Network until she fell asleep on the sofa bed. She didn’t even eat.

“Yes, she’s had a long day,” her mother observed as we dined in the next room.

Later Soleil insisted on washing the dishes. As I dried, she told me that she had moved to the United States from Haiti to give her kids a better life. “Without this abortion, I don’t think that Marianne could graduate high school and go to college,” she said, tears running down her face. “Thank you for helping us.”

It was the least I could do.

In his book “Spiritual Activism,” Rabbi Avi Weiss wrote, “I was once involved in activism because I enjoyed it, but now I have come to believe that a true activist is one who takes no pleasure from it. Now I’m an activist because I feel I have no choice; there are things I believe I simply must do.” The greatest sin, in fact, is not to act. This was what Haven meant to me.

LaShawna came from Philadelphia with her cousin Sandra. Each had left a toddler in her mother’s care. After dinner, they called home on their cell phones.

“Don’t cry,” I overheard each of them say at different points in their conversations. “Mommy loves you. I’ll be back tomorrow.”

We watched TV. During a commercial, I excused myself to use to the bathroom. When I returned, the women were whispering. They stopped when they saw me.

The situation made me nervous. “What?” I asked.

Sandra thrust her chin toward my ketubah, the Jewish marriage document that hung on the wall over my couch. It has two columns — one in Hebrew, one in English — that outline the egalitarian terms of our marriage, and is decorated with a Florentine flower pattern. “You Jewish?”

“Yes, why?” I held my breath.

“I just want to know if all Jews are stingy,” LaShawna said.

Her cousin glared at her. “LaShawna! I told you not to say anything!”

I sighed. Part of me wanted to lash out, to remind them that I paid their way to my apartment, bought them dinner, offered them a place to sleep, and would wake up with them at 5:15 tomorrow morning to take them back to the clinic in a cab that I would also pay for. The other part of me understood the question completely: Over the years, I noticed that some of the worst slumlords in many cities are Jewish; shops that price gouge the most in low-income neighborhoods are too often owned by Jews; and there’s no shortage of stereotyping in the media, with Jews portrayed as money-grubbing misers. I thought about my grandmother. “There’s good and bad in all people,” she frequently said whenever someone made a nasty remark about some other ethnic group.

“No, we’re not all stingy,” I replied.

The women nodded. We went back to watching American Idol.

The next morning, we crowded into the back seat of a taxi. Halfway to the clinic, LaShawna asked me for $20 to help pay for the garage where they’d parked their car the prior night. Was she manipulating me, taking advantage of my desire not to appear tight-fisted? I pursed my lips and looked out the window. Park Avenue was a ghost town so early in the morning. A few hours later, investment bankers would line up at gourmet shops and buy $14 sandwiches. Our Jewish tradition demands that we disperse privilege evenly. I opened my wallet and handed her the bill.

During these days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the words of Rabbi Ayelet S. Cohen resonate with me: “May this season of beginnings be a time of renewal, possibility, and hope.”

It’s been many years since I hosted these women through Haven. I hope that the small role I played in their lives helped them achieve renewal, possibility, and hope.

Editor’s Note: Names have been changed throughout this article to protect privacy.

Suzanne Reisman has worked in community development in New York City for 15 years. Her writing has appeared in New York Nonprofit Press, Metro New York, City Limits Magazine, Young Children, Just Cause, and New York Family. Her first book is “Off the (Beaten) Subway Track,” a travelogue about/guide to unusual places and things to do in NYC. Suzanne has also written about her experiences with Haven in Magnolia: A Journal of Socially Engaged Literature.”

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Suzanne Reisman

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!