Mendelssohn’s Tea Pot: How Artists Reinvent the Past, and the Jewish Future

Lately, virtually everyone I know who has some kind of association – professional, emotional, familial, religious or intellectual – with the American Jewish community has been reading tea leaves, trying to figure out, in the wake of the Pew Research Center findings, what the future might hold.

I, too, have been reading tea leaves (Darjeeling, anyone?), but the ones I find at the bottom of my tea cup belong to Moses Mendelssohn, the celebrated 18th-century German Jewish philosopher who sought valiantly to come up with a series of strategies to align Jewishness with modernity.

In case you think I’ve lost my mind, I assure you that I’m in complete possession of my faculties. When I speak of Mendelssohn’s tea leaves, I’m not engaging in an elusive form of cultural archaeology or indulging in sci-fi fantasy (although that would be fun). I mean for you to understand my reference metaphorically: as a call to think creatively and even fancifully about the Jewish experience. My summoning up of Mendelssohn’s tea leaves, you see, grows out of an encounter between art and history, between the free exercise of the imagination and the act of reconstruction, an encounter that sets my heart racing – and no, caffeine is not the culprit.

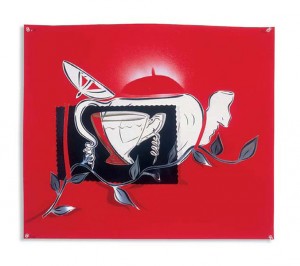

What I have in mind here is the remarkable work of Izhar Patkin, titled Judenporzellan, whose multiple re-imaginings in paper and on canvas of Mendelssohn’s tea pot and his tea cup as well as the table on which these two items rested and the fussy bibelot that surrounded them blurs the traditional boundaries between art and history even as it invigorates the relationship between them.

Patkin takes a seemingly ordinary household implement – a tea pot – and by peeling away layers of time and meaning, exposes it as an instrument of coercion. It turns out that German Jews of Mendelssohn’s time and place – late 18th century Prussia – were forced to purchase any number of humdrum domestic objects – an entire tea service, say, or a set of figurines – from a porcelain factory owned by Frederick II. A form of taxation, an unwelcome reminder of the Jews’ second class status, these items, many of them poorly and ineptly made, were known far and wide as Judenporzellan, which gives Patkin’s series its name. But then, the artist isn’t just mining the past for historical curios. His treatment, which encompasses collage, stenciling and the canny juxtaposition of objects in space, enables Mendelssohn’s tea pot to emerge as a thing of beauty; in Patkin’s hands, the second-rate and shoddy becomes a work of art.

Patkin’s project suggests that American Jewry is very much alive, even awash in creativity, rather than the sluggish, deracinated, tentative institution depicted time and again in contemporary sociological studies and newspaper accounts, an institution seemingly more inclined to stifle the arts than champion them. And it has lots of company. In fact, were we to take the measure of American Jewish life using culture rather than demography as its yardstick, we just might sing a different tune: a cheerful ditty rather than a sorrowful dirge.

Consider Sukkah City, for instance, which applied the latest architectural theories of space and design to the ancient structure described in the Bible – and with results that were nothing less than eye-opening and crowd-pleasing.

Consider as well the musical stylings of Alicia Jo Rabins of Girls in Trouble, which puts a new spin on ancient Jewish melodies and the stories in which Jewish women loom large. Or how about the immersive, week-long retreats generated by Tent: Encounters with Jewish Culture, an initiative of the ever-fertile Yiddish Book Center, which combine community with the cutting-edge?

As these examples make clear, Jewish cultural expression doesn’t just protect and preserve the Jewish community’s patrimony. Reaching forward as well as backward, the Jewish cultural arts extends its shelf life, its reach, and does so in ways that are fresh and bold, and, arguably, even downright irreverent at times. Anything but static, contemporary Jewish cultural expression reshapes our heritage, endowing it with new forms and meanings.

Of course, I’m partial to culture. Having just launched a brand-new graduate program in Jewish Cultural Arts at the George Washington University in August 2013 while also preparing to launch a sibling – a graduate program in Experiential Education and the Jewish Cultural Arts that will open its doors in June 2014 – I do, indeed, have a horse or two in this race. But then, I wouldn’t have set about constituting a brand-new discipline whose simultaneous embrace of the arts and of new forms of teaching hopes to stretch the parameters of Jewish learning and foster a network of people trained to harness the Jewish community’s cultural energy were I not a believer.

By the time you get to the end of this article, right about now, I’d like to think that you’ve also become a believer, if you weren’t already. Let’s put our collective faith in Jewish cultural arts and drink to Mendelssohn and his tea pot, shall we?

Jenna Weissman Joselit, a historian of everyday life and a longtime columnist for the Forward, is the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of History at The George Washington University, where she also directs its Program in Judaic Studies and its MA in Jewish Cultural Arts.

Enjoy this article? Support independent, progressive Jewish journalism. Support Zeek today, and know that you’ll be helping us start 2014 as a strong, sustainable magazine. Thank you!

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Jenna Weissman Joselit

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?