Broken Justice and the Death Penalty: A Q & A with Jen Marlowe, Co-author of "I Am Troy Davis"

I first encountered Jen Marlowe’s work thanks to blogger and frequent Open Zion, Ha’aretz, and Forward contributor Emily L. Hauser. She had written a review of The Hour of Sunlight: One Palestinian’s Journey from Prisoner to Peacemaker, which Marlowe had co-authored with Sami al-Jundi. I read the book, found it powerful though not always comfortable to read — and ultimately partnered with other local organizations to bring Marlowe to my town to speak about her work.

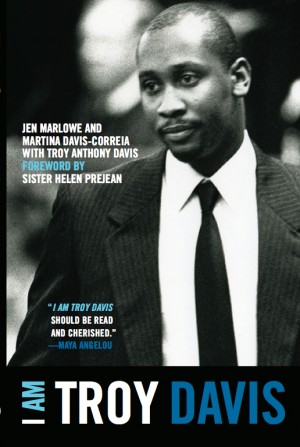

I knew then that she was already working on a new book, also co-authored. That new book is now out. It’s called I Am Troy Davis, and it’s written by Marlowe and Martina Davis-Correia along with Troy himself.

Much like The Hour of Sunlight, I Am Troy Davis shines a spotlight on systemic injustice not by speaking in generalities, but by telling one person’s story — and thereby opening up the experiences of countless others who are in similar shoes. I spoke with Marlowe about these two books, how her Judaism animates her work, and what we as readers can do to strengthen justice in an unjust world.— RB

ZEEK: Tell us about I Am Troy Davis. What is the book, and how did you get involved with it?

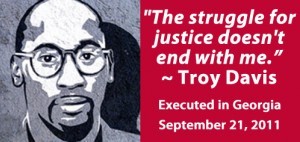

JM: I Am Troy Davis grew out of my relationship with Troy and with the Davis family. Troy was a man who spent 20 years on Georgia’s death row despite a very compelling case for his innocence. When that compelling case came to the attention of human rights organizations and then the media, it led to a worldwide movement, both to try to prevent the travesty of justice of Troy being executed, and also toward the abolition of the death penalty, especially when there’s such recognition of the human error that the system is rife with. A system like that has no business making the decision to take a life.

The book grew out of my friendship with him and his family. It was my way of helping them tell their story.

ZEEK: How did you and Troy meet, and how did you become friends?

JM: Troy had four execution dates, three of which he survived. After his first execution date, July 2007 — which he survived by only 23 hours — his sister Martina was speaking on Democracy Now. I hadn’t heard about his case, but when I heard her speak it was clear that this woman was a force of nature herself. I became curious about the brother whose innocence she was fighting to prove.

Martina spoke about her double struggle: fighting for his life, and for her own life. She’d been diagnosed in 2001 with terminal breast cancer, and given six months to live — and here we were, six years later, and she was still alive and still struggling both for her own life and her brother’s.

I got curious. So I started looking things up. It’s often the case that if we have the sense that the mainstream media isn’t giving us full information, but we know where to dig for information, we can find it. And I found the Amnesty International report, “Where is the justice for me”, which laid out in empirical black-and-white all of the aspects of Troy’s case, which were so deeply problematic. Each piece of evidence I read about, my jaw dropped further.

There had never been any physical evidence linking him to the murder. His conviction was entirely based on witness testimony, the majority of the witnesses having since recanted and/or said they were coerced or intimidated by police into implicating Troy. And one of the people subsequently named as the perpetrator was the person who had first given Troy’s name to the police.

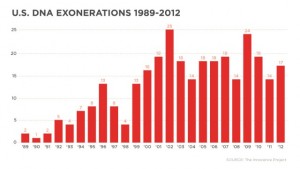

I was horrified at what I assumed at that time was a very unusual situation. I thought it was an aberration. Only later did I realize how typical his case was. The only thing that was not typical was the media attention. But so many aspects of what made his case problematic are emblematic of our death penalty system and our criminal justice system.

I wrote him a note in prison. I just meant it to be a note of solidarity and encouragement. But he wrote back to every single person who reached out to him, even once he started getting sack-fulls of letters. And a friendship developed over correspondence. Through that friendship he planted the seed that I might be a part of helping his family tell their story. I met his sister about a year later, and a few days later, I emailed her to ask if she wanted me to partner with her on this telling of her story.

ZEEK: So you met Martina first.

JM: Yes, at that point I had not yet met Troy in person. Our friendship had consisted of letters and then phone calls. But when I made my first trip to Savannah to work with Martina, that was also my first time visiting him on death row. I went with the family, to Jackson, GA. That was the first of many visits. The experience of writing the book deepened the friendship both with Troy and with his family.

ZEEK: It’s interesting to me that you’ve co-written two books – The Hour of Sunlight and I Am Troy Davis — in which your writing skills are helping to give voice to people whose narratives might not otherwise have been heard, people who have experienced oppression. Do you see a connection between them?

JM: The two projects do feel related in a lot of ways. What I strive to do with all of my work is for my work to provide a platform for people to speak and to be heard. I don’t see it at all as me giving a voice to those who don’t have a voice: People have voices!

ZEEK: It’s a matter of amplification.

JM: Yes. Using whatever tools I have to amplify those voices so their critically important stories can be heard — that’s definitely a through-line between the two books and a lot of the rest of my work.

Sami Al-Jundi spent 10 years in an Israeli prison; Troy spent 20 years on death row. I sent Troy a copy of The Hour of Sunlight right after it came out, and we had some interesting conversations about his experience on death row and what about Sami’s experience in prison felt familiar to him and what was different.

ZEEK: That must have been fascinating, hearing Troy’s reactions to Sami’s story.

JM: My work always comes out of close relationships, because for me the personal and the political are inextricably linked.

ZEEK: Do you see your social justice work as stemming from your Judaism and Jewish values? Was this kind of social justice focus part of your Jewish upbringing?

JM: Absolutely. I grew up very active in the Reform Jewish movement, in Reform youth group and Reform summer camps, and one of the things that really called to me very deeply about the youth group movement was the social justice component. My memories of those formative years — it was the ’80s, so it was marching against apartheid. In my mind, Judaism equaled social justice, equaled taking action for social justice. I see those years as my training grounds for the activism that came after.

ZEEK: I think that, of all of the contemporary movements, the Reform movement has worked the hardest to put some notion of tikkun olam at the center.

JM: That was the largest takeaway for me from those years of involvement. It’s the part of my Jewish heritage that really took root and grew in me.

ZEEK: I’ve heard this story before, but our readers haven’t: tell us how you wound up co-writing The Hour of Sunlight?

JM: The protagonist, my coauthor of that book and the person who the book is about, is Sami al-Jundi. He’s a Palestinian who in his youth had decided to fight against Israeli occupation using the only means that he understood, which were militant means. He ended up spending 10 years in Israeli prison, and emerged from that experience committed to nonviolence and peaceful reconciliation, and to taking on the fight for his people’s freedom, justice, and dignity nonviolently and in partnership with Israelis.

That book happened because he was a dear friend, more like a brother. We had worked together closely for many years in an organization called Seeds of Peace. I had lived for four years in Jerusalem, and Sami’s family was my family during those years. And all of the staffers at Seeds of Peace always told Sami, Wow, you should write a book! And he always told us, No, my life’s ordinary. But one day he came to me and said he was ready to write that book. My passion was in some ways rooted in his statement that his life wasn’t extraordinary. Because so many pieces of his story are part of the quintessential Palestinian narrative. But it’s not a story that people in this country, especially Jewish Americans, have a lot of access to. I wanted his story to provide a window into that understanding.

And then of course his commitment and passion for working toward peace with dignity and equality for all human beings — Jewish, Palestinian, Israeli, Christian, Muslim — was such a deeply held commitment, and I thought that was important model to hold up. We hear so much about “there’s no partner for peace,” or “they” don’t want peace — and you hear that from both sides, the “they” depends on who’s speaking! I felt that if readers could only meet Sami, he would challenge that. He had gone through great suffering and came out of it truly committed to the notion that in order for any child to have a good future secured, every child needed to have a good future secured.

ZEEK: I’m glad you mentioned Sami’s statement that his life wasn’t extraordinary, because I wanted to touch on that some more. This question of ordinary/extraordinary seems to be at the heart of both of these enterprises. You mentioned earlier that you had thought Troy’s story was extraordinary, but it turns out to be a very typical experience.

JM: I used to believe that by and large our justice system worked really well, and that when it broke down those were exceptions, that we had safeguards in place. And the more that I’ve dug into the reality of our criminal justice system, I’ve come to recognize that the death penalty is a particularly horrific piece of public policy, but it’s not the whole problem! It’s the sharp edge of a very broken criminal justice system.

Our justice system is riddled with racism, riddled with error, riddled with bias and arbitrariness. Our Constitution is supposed to guarantee us equal protection under the law, but it doesn’t. If you are a person of color, a person who comes from poverty, you do not have the same access to justice as if you are a person of means. All of these things are systemic problems in our criminal justice system. We have a human rights crisis in this country.

We incarcerate a larger percentage of our population than any other nation in the developed world. We like to think of ourselves as the beacon of freedom, justice, democracy, but our reality is different. Troy’s case was not an exception. What was exception was his family, and Troy, and how courageously they fought and with what resilience they did so.

ZEEK: Where do you find cause for hope? Or maybe I should ask, do you find cause for hope at all?

JM: Absolutely there’s cause for hope. First and foremost, I find it by standing in solidarity with the people whose stories I’m trying to amplify. The Davis family, for instance: in six months they lost three warriors for justice. Troy’s mother, Virginia, who died a few months before Troy (from a broken heart, her daughter said, unable to bear the prospect of another execution date); Troy’s execution; and then Martina passed away, having outlived her initial prognosis by a decade. Even after having lost those three, the rest of the Davis family is still standing. And they’re still fighting.

I was just in LA with them last week, and Martina’s son DeJaun, who’s now a phenomenal 19-year-old man, was talking about his struggle to overcome the trauma of losing his grandmother, his mom, and his uncle —who was really his father figure — in such a short period of time. But he’s coming out of that ready to pursue his own dreams to do great things in the world, and speaking out about the criminal justice system.

For me the hope comes from these warriors that I stand side by side with. When I’m in Israel and Palestine, it’s not that I don’t recognize how bleak the situation is, but the act of struggle, of seeing how people are choosing to struggle with dignity, that gives me hope. And motivation. What right do I have to say, “Oh, this is too depressing,” when the Davis family isn’t saying that, when my friends in Gaza aren’t saying that, when my friends in Tel Aviv are standing with my friends in Budrus or Bil’in and not saying that?

I’m working now on a documentary film about Bahrain. Activist friends of mine there have been arrested, tortured, imprisoned, and when they’re released they say, “I’m still fighting, I’m going to go out and demonstrate tomorrow.”

ZEEK: I’d been about to ask what was next for you, so tell us about that film?

JM: The working title is Witness Bahrain. It’s footage I filmed about a year and a half ago. I spent about three weeks there, until I was caught and deported. While there, I was embedded with human rights and pro-democracy activists who have been struggling to bring reforms, democracy, and respect for human rights to Bahrain. All of this is part of the Bahraini Arab spring, which took off in February 2011, inspired by the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. I should have finished the film long ago, but I had to finish the book!

And I’m still spending a lot of time with I Am Troy Davis, because writing and publishing is only 40% of the work. The rest is helping the thing grow its legs so it can walk in the world, and do its work in the world. I want I Am Troy Davis to be a platform for critically needed conversations about the death penalty and the justice system, and to provide insight into the human impact of the death penalty and how it impacts real human lives — and it can only do that if people know about it and are reading it.

For me it’s not just a creative project, it’s a mission. Troy asked us to continue to fight this fight — those were among his last words when he was strapped on the gurney, before he was killed.

ZEEK: Assuming that readers come away galvanized, what can we actually do?

JM: The good news is, there’s a lot to do right now. We’re at a turning point in this country when it comes to abolishing the death penalty. We’ve had huge successes in the last few years, partially growing out of the injustice that happened to Troy, and people’s shock and outrage at that, which opened eyes. There are several organizations which are working to repeal death penalty — Equal Justice USA, Amnesty, the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty — and their websites will be able to direct people to action at the state level.

If you live in a state where the death penalty is still legal, of which there are 32, you can find out what’s happening locally. Because the campaigns are happening on a state-by-state basis. And even if you live where the death penalty has been repealed, there are still ways to support that struggle.

There are also groups springing up all over the country based on Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow, a phenomenal indictment of the criminal justice system. There’s been different versions of No New Jim Crow groups springing up, looking at what’s happening in our criminal justice system in the name of the drug war and the “tough on crime” movement, and these folks are connecting a lot of the dots.

There’s a lot of good work to plug into right now. Find out what’s happening near you. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel; educate yourselves and then you can find out what’s out there and lend yourself to that.

ZEEK: Makes me think of that old saw from Pirkei Avot: it’s not incumbent upon us to finish the task, but neither are we free to refrain from beginning it. Thanks for taking the time to talk with us.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Rabbi Rachel Barenblat

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- New Depths in Jewish-Muslim Dialogue: Jewish Privilege

- This Year's Revelation

- Broken Justice and the Death Penalty: A Q & A with Jen Marlowe, Co-author of "I Am Troy Davis"

- Tu B’Shvat Reflections on Parenthood, Extreme Weather, and the Human Family Tree

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!