Hey You, Are You Confronting Jewish Racism? Ferguson, Race & Public Space

On Saturday, police fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, near his house in Ferguson, Missouri, keeping Ferguson, the civil unrest there, and deeper issues of racism and police misconduct in the national spotlight – including Washington Post journalist Wesley Lowery’s account of his unprovoked arrest.

Brown is the most recent in a long string of unarmed black youth who have been shot, one that includes Trayvon Martin, murdered while walking home from buying candy, and Jordan Davis, another unarmed black youth killed for refusing to turn the music down in his car. Older black men are not immune; Eric Garner was killed by an apparent police chokehold for the offense of selling untaxed cigarettes.

As the civil unrest in Ferguson re-launches much-needed conversations about race — and racism — US Jews must see this as a call to action on injustice broadly as well as a time to kickstart difficult conversations within the Jewish community. And not just around the kind of explicit, hate-filled racism we heard from Donald Sterling this spring, but pressingly, around the more subtle undercurrent that enables more explicit racism but often goes, unnoticed, unremarked upon, and thus, unchecked.

The men who killed these youth justified their violence by saying they felt threatened. The Talmud does teach us that self-defense is not just allowed but required. But there’s a caveat: There must be reason to believe someone is trying to kill you. Yet Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Jordan Davis were not trying to kill anyone. All they wanted to do was live their lives, like so many other young people of color. Their mere existence as black teenagers in US public space was perceived as a threat. A 2013 Urban Institute study showed that murder is much more likely to be ruled justified if the killer is white and the victim is black compared to the reverse situation. That trend is so pervasive that it was considered newsworthy last week when a jury found Theodore Wafer — the white man who murdered unarmed black teenager Renisha McBride when she knocked on his door, seeking help after a car accident — guilty of second-degree murder.

Prior to Brown’s murder, much of the mainstream discourse around these murders was about Stand your Ground laws, also referred to as “shoot first” laws. The US Jewish community largely opposes these laws already, consistent with the Shulchan Aruch’s guideline that “s/he has a right to defend himself, but if s/he was able to use less force but caused greater injury then s/he is guilty.”

Unfortunately, as Brown’s murder by a police officer — rather than a civilian “standing his ground” — demonstrates, the policies themselves are not the source of the problem. While the racial discrepancy in murders being ruled “justified” is worse in Stand Your Ground states, it is a major problem nationally. The core problem is that skin color impacts whether behavior is seen as threatening or justified; Stand your Ground just amplifies the damage.

Too many Americans perceive threats through the lens of a dehumanizing stereotype: that young men of color are a menace. This perception is extremely dangerous and too often used to justify murders like these, while playing out in countless smaller ways in everyday life that add up to meaningful, debilitating discrimination.

If we as a Jewish community are serious about the most vital Jewish value of pikuach nefesh, the preservation of human life, we need to turn a critical eye not just toward Stand Your Ground laws but also to the more subtle, insidious prejudice that enables it.

Too often at American Jewish events, I hear offhand comments with racist undertones. On the way home from a recent Shabbat dinner, for example, someone responded to a black, homeless newspaper vendor saying that “the neighborhood has gentrified but the people haven’t.” Earlier, someone had joked that I must be Korean because I’m from Annandale, a majority-white suburb of DC known for its concentration of Korean businesses.

In both cases, the quips were based on more impalpable notions about space. Just as “Jewish neighborhoods” often earn that reputation not by actually being majority Jewish but simply having a significant number of people who are visibly Jewish, the same is true of other “ethnic” enclaves. For many, the status quo is a “White, Christian America,” and white privilege subtly and not so subtly places everyone who’s not white beyond the norm. The mere visible existence of minorities gives them an outsize presence in the majority conscious (hence the “War on Christmas”), so Annandale becomes “Koreadale.” Similarly, longtime black inhabitants of recently-gentrified DC neighborhoods may suddenly find themselves seen as unwelcome by some new (white) residents due to the latter’s sense of entitlement to that public space.

These examples, while small, speak to a larger sense that white ownership of space is the norm and people of color are unwelcome. That racial double-standard is dehumanizing – it says that people of color do not have a basic right to exist in public space in the same way white people do. That sentiment was particularly glaring at another Jewish event, where someone paired “Custer’s Last Stand” with “savage” in a word association game. A group defending its civilian village against a military force actively engaged in genocide can only be considered savage if (as many US history books teach about Custer’s Last Stand) you don’t recognize the right of people of color to stand their ground against white attempts to kill them. While games and jokes are small things, they feed into ideas about who is allowed to exist in public space that can have, and historically in the US have had, major consequences.

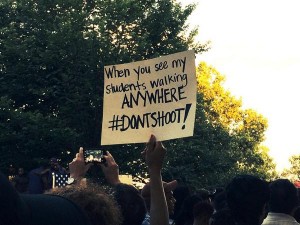

Discussions about white privilege often focus on economic issues: access to jobs, housing, educational institutions, etc. Important as it is to recognize disparities in who has historically had access to those means of building success and wealth, beyond economics, the privilege of walking down the street without being perceived as a threat is perhaps as fundamental as you can get.

Since Brown’s shooting, social media have become a hub for sharing disgust and anger at racism, focusing on racial profiling, police misconduct, and racial disparities in policing, with hashtags like #guiltyofbeingblack and #NMOS14, a national moment of silence to honor victims of police brutality; it prompted plans for vigils in cities around the country. The poignant Tumblr “If They Gunned Me Down” challenges mainstream media portrayals of black youth by posting pictures of themselves in stereotypically “black” outfits (hoodies, baggy pants, visible tattoos, beanies or do rags, etc.) juxtaposed with ones of themselves in “successful” outfits (graduation robes, suits, military uniforms, etc. When white Jews make disparaging comments about “thugs” or “bad neighborhoods” we are perpetuating the dehumanization that has resulted in this week’s protests (both virtual and on the streets of St. Louis). More broadly, we are bolstering ideas about public space that enable white men to shoot unarmed black boys with the expectation that it will be ruled justified.

I don’t write any of this to claim to have the answers. I’m also guilty of internalized racism, having the occasional racist thought or making an unwitting comment. It’s nearly impossible to live in America without internalizing some racism and stereotypes. And as Erika Davis wrote in “Am I a Racist? Tackling the Tensions of an Inclusive Multiracial Jewish Community.”, that applies in the Jewish community as well. I am lucky to have friends who have been patient in kindly calling me out as I slowly learned to do somewhat better. I’m especially grateful when that happens in Jewish settings because, frankly, it’s unusual. And that’s the thing: it shouldn’t be.

Jewish institutions almost never initiate communal conversations about race. A few months ago there was recently a refreshing exception to that in New York. The Jewish Multiracial Network held a groundbreaking meeting titled “I’m Not Racist, Am I? A Conversation About Identity and Race in the Jewish Community.” It focused on the ways in which broader racial dynamics play out in Jewish communities. One common theme that kept coming up was that many white Jews insist on explanations for how Jews of color came to be at synagogue, or even assume that they are there as a nanny or security guard rather than as a congregant.

Conversations about why that is problematic and hurtful are important, as JMN recognizes, for the sake of klal Yisrael — if the dominant Ashkenazi group alienates Mizrahim, Ethiopian Jews, Jews by choice, adoptees, etc, we are all weaker for it.

But beyond the impact for individual Jews and Jewish communities, norms for who belongs in Jewish spaces are linked with those for public spaces more broadly. If we do not explicitly address our internalized racist ideas about who belongs both in Jewish spaces and in public spaces more broadly, we allow ourselves to perpetuate dehumanizing stereotypes that, taken to extremes, justify those who violate Judaism’s most important principle.

Rachel Metz is a DC-area-based analyst and occasional writer on social justice issues, whose writing has appeared in In These Times, the Jerusalem Post, Washington Post, Baltimore Sun, and Washington Jewish Week. Those roughly correspond to the places she has lived - southern Virginia, Chicago, southern Israel, and the Navajo Nation, each of which has impacted her perspective on race, space, and privilege. Since returning to the DC-area she has continued to engage with social justice issues professionally (focused on education) and as a volunteer leader with Jews United for Justice.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Rachel Metz

More articles in