Should Rabbis Proselytize Non-Jewish Spouses? A Response to JTSA Chancellor Arnold Eisen

The Trouble with Celebrating American Diversity & Jewish Exceptionalism

Arnold Eisen, chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, the spiritual and intellectual center of the Conservative Movement, recently published an interesting and in many ways courageous op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, “Wanted: Converts to Judaism.” In light of growing rates of interfaith marriage among American Jews, Eisen has taken a step outside the conventional tack of trying to prevent intermarriage. Instead he suggests that Conservative rabbis should now actively encourage the non-Jewish spouses of Jews to convert to Judaism. His reasons are two-fold. First, “we [the Jewish community] need more Jews.” And second, Judaism “has lots to offer.”

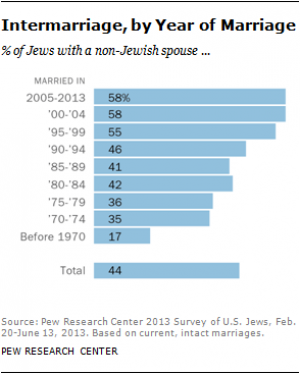

Eisen has recognized that in contemporary American society, preventing Jews from marrying non-Jews is simply impossible – and, I might add, not even fully desirable. Most American Jews understand that the pluralistic nature of American society creates optimal conditions for inter-ethnic and inter-faith marriages more generally, and for the most part America is a better country for it. Most would correctly view congressional legislation banning Jews from marrying non-Jews as anti-Semitic. Jews want to live in a society where other ethnic groups intermarry and where they can intermarry, but choose not to. What is the basis of this exceptionalist argument? Survival. But that is true of all minority groups in America, yet many American Jews do not seem to translate their inherent need for survival with the survival of other similar groups.

In the last century, the Reform movement proposed patrilineal descent as its “solution” to intermarriage, arguing that the child of a couple with one Jewish parent was sufficient to determine the Jewishness of the child on the condition that the child was raised “Jewish.” This, of course, solves the problem of the children, but not the parents, of the consequence of intermarriage, but not the phenomenon. Perhaps this is because Reform Judaism understands that there is something problematic about a blanket protest against intermarriage of Jews and non-Jews while celebrating the diversity and inter-raciality of American society.

A Brief History of Jewish Attitudes about Conversion

Eisen’s attempt to minimize the impact of intermarriage by encouraging the non-Jewish spouse to convert to Judaism is not novel, although it is new as policy for the Conservative movement.

When Rabbi Eric Yoffie, then the leader of the Reform movement, made a nearly identical proclamation for his own community almost a decade ago, his proposal was the topic of considerable controversy. Yoffie’s position is an extension of a similar idea proposed by then leader of the Reform movement Rabbi Alexander Schindler in 1978 and adopted by the movement in the 1990s. But there are numerous other precedents for Eisen’s call to seek Jewish converts. As Michael Staub notes in his book Torn at the Roots: The Crisis of Jewish Liberalism in Postwar America, in the 1970s Jewish communal leader Balfour Brickner and Conservative rabbi Asher Bar-Zev called for Jews to actively seek converts. Bar-Zev’s reason was to increase the Jewish population (Eisen’s “we need more Jews”), responding to the fears around the zero population growth of Jews at that time.

Bar-Zev argued that there was a moral problem for Jews to advocate zero population growth for the world with the exception of Jews. Milton Himmelfarb and others made such arguments basing themselves on the depleted population of Jews resulting from the Holocaust. For the Jewish exceptionalists, zero population growth for Jews was tantamount to collective suicide. Bar-Zev viewed this argument as morally problematic yet acknowledged the problem. As a solution he suggested actively missionizing unchurched Christians to increase the Jewish population while adhering to the policy of zero population growth.

More recently, Rabbi Harold Schulweis, a student of Mordecai Kaplan and respected Conservative rabbi, developed an entire educational program to proselytize “unchurched” Americans who did not consider themselves part of any religious community. Schulweis wrote many essays exploring the idea of conversion in Jewish history, showing, correctly I believe, that the “myth” that Jews never proselytized is simply inaccurate. He taught classes on basic Judaism in his synagogue in Encino, California, targeted for non-Jews that were attended by thousands of interested seekers, some of whom converted.

Indeed, as Eisen notes, the rabbinic attitude toward conversion is complex. The normative halakhic tradition does not advocate proselytizing.

The sages say some very negative things, as well as some very positive things, about converts. Historically, the picture is even more complicated. According to Yeshiva University Jewish historian Louis Feldman, there is some evidence of Jews actively seeking converts during the Hellenistic period. Others argue similarity in the Middle Ages. The great 16th-century kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria developed an entire metaphysical system of creation that included fallen divine sparks that became embedded in the world, and in the bodies of non-Jews, that needed to be redeemed. This could easily be interpreted to advocate seeking converts who housed those fallen sparks. While Luria’s position was likely about bringing back conversos who had converted to Christianity in Spain and Portugal the previous century, the notion of finding these “fallen sparks” and bringing them back into the Jewish fold is not an unprecedented idea.

In some way, the Lurianic idea of creation is a theology that argues for the necessity of conversion.

Conversion: A Transformational Experience (Not an Easy “Fix” to Jewish Population Stats)

Eisen argues that today conversion is less about eternal salvation and more about “salvation in the here and now.” Here he is quite close to Shulweis, who wanted to offer Judaism as a spiritual tradition to be included in the myriad alternatives available to American seekers who left their traditions of birth.

Yet there is a substantive difference between Shulweis and Eisen, and this difference is the central part of my critique of Eisen’s position. Shulweis’s theory of proselytizing was not about intermarriage nor was it focused primarily on the spouses of Jews. Rather, it was about offering Judaism to the American seeker of religious meaning. He did not want to take these seekers away from traditions to which they belonged. His thinking was not polemical, nor was it overtly pragmatic. Shulweis celebrated people who found spiritual sustenance in their home tradition, or on another spiritual path. Those people were not his audience. Shulweis thus offered what I would call “passive proselytizing,” offering Judaism to those who were self-motivated. It retains the ethos of voluntarism endemic to a pluralistic society.

Eisen’s position is quite different. For him, seeking conversion is primarily about solving the practical problem of the inevitability of Jews marrying non-Jews. It is surely not coercive, but it is not purely voluntaristic either. There are two main problems I have with this approach. First, it is hypocritical unless it recognizes reciprocity. How would Eisen relate to the Presbyterian minister seeking to convert the Jew in her marriage to a Presbyterian? Or, if we make a distinction between a minority verses a majority religion, an imam seeking to convert a Jew married to a Muslim? I assume he would not support either. And this is precisely the problem.

Eisen’s position too easily takes us back to the problem of the exceptionalist argument I stated at the outset. Jews are arguably the most successful and integrated minority in America. We cannot maintain that hard-earned status and also maintain that we are exceptions. I think such a move is hypocritical even as I understand its attraction. If we try to convert the non-Jewish spouse we are, in essence, inviting the non-Jewish spouse to try to convert the Jew. What then has been accomplished?

My second problem with Eisen’s approach is that it flattens the very act of conversion, something I consider to be one of the most profound and complex things human beings do with regards to religion. One need only read Augustine’s Confessions to understand the intense existential impact conversion has on the convert and the effort it takes to make that difficult life-transforming transition.

I think Eisen understands this, which is why he suggests that today, in Max Weber’s “disenchantment of the world,” people are less interested in immortality and more interested in spiritual meaning. This may be true, but I do not think it diminishes the existential intensity and complexity of conversion. If we view Judaism, like any religion, as a deeply complex and spiritually nuanced lifestyle and if we view conversion as a profound and radical choice that not only separates one from one’s spiritual past but places one inside a different covenanted community that requires a deep commitment of body and soul, conversion should not be taken as the solution to a sociological problem.

Is the Mainstream Jewish Community Finally Coming to Terms with Jews Marrying Outside the Fold?

Suggesting conversion as a solution to intermarriage too easily diminishes Jewishness to a kind of social engineering, in short “be Jewish so that Jews are not intermarried.” It’s almost as if we are asking the non-Jewish partner to convert in order to do the Jewish community a favor. We would not, according to Eisen, proselytize this non-Jew if they weren’t married to a Jew. Nor would Eisen seek, as Shulweis does, to open Judaism to the unchurched American populace. For Eisen, I think, “seeking converts” is a tool or a means to justify an end that is not the problem of the potential convert. One could imagine a non-Jewish spouse saying, “Just because I married a Jew doesn’t mean it is incumbent upon me to solve a Jewish problem.”

Having said all that, I deeply applaud Eisen for taking a step Conservative leaders before him have refused to take and for realizing that throwing the same failed policies at a problem that is endemic to American Jewry will not yield the desired results. Eisen has reached the conclusion that American Jewry must come to terms with intermarriage. For a leader of the Conservative movement, that is indeed courageous.

A Changing Jewish Strategy for a Post-Ethnic America

In the spirit of conversation, I would like to propose another approach.

In my book American Post-Judaism: Identity and Renewal in a Postethnic Society, I argue that American Jewry is changing in precisely the same way America is changing. We are reaching, or have reached, the final stages of multiculturalism, based on secure and stable ethnic anchors, and have begun to live in what David Hollinger calls “Postethnic America.” Historians in the future may point to President Obama’s election as the beginning of that turn. Not only is he the first African-American president, he is the first mixed-race president.

As a result of sustained rates of intermarriage, most American Jews have close non-Jewish relatives. Many are themselves multi-ethnic. The intermarriage rate among American Jews is largely commensurate with many other ethnic minorities, making them nothing more than “good Americans.”

One of the consequences of this postethnic turn is the predominance of non-Jews who are now related to Jews and married to Jews. Given that this comes on the heels of multiculturalism and the celebration of diversity, many of these non-Jews who live with or in close proximity to Jews are equally proud of their own heritage even as they feel attached in some way to the Jewish community. Some will certainly choose to convert, and the Jewish community should welcome them with open arms. Many will not. Not because they do not like Judaism as much as because they want to maintain or celebrate their own identities. This is what multiculturalism has cultivated. And yet many want to be part of the Jewish community because of their familial connection to Jews. A Place in the Tent: Intermarriage and Conservative Judaism, published back in 2004, explored informal ways synagogues could integrate these families into congregational life. In 2005, a Conservative policy statement “Al Ha-Derekh: On the Path” suggested reaching out to the non-Jewish spouses as “potential converts.” Thus there has been some movement in liberal American Judaism toward the realization that non-Jews are increasingly becoming a part of the Jewish community. Eisen seems to be moving in another direction by asking his rabbis to encourage these non-Jews to convert to Judaism. As I read it, his program would like to minimize that non-Jewish constituency by making Jews out of as many as possible.

A different solution to this dilemma was proposed by the late Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, founder of the Jewish Renewal Movement, who passed away July 3rd at the age of 89. In an unpublished encyclical, “Concerning Gerey Tzedek (Full Converts) and Gerey Toshav (B’nai Noah) in our Communities,” Schachter-Shalomi criticizes the way conversion to Judaism in America has largely become a tool to counter intermarriage and has lost the deep spiritual and existential content of what conversion should be about. However, he recognizes and even celebrates the fact that non-Jews have taken an interest in the spiritual resources of Judaism or want to celebrate with their Jewish families.

He proposes a (re)invention of the idea of ger toshav, a non-Jew who resides inside the Jewish community as a non-Jew. This idea may have historical precedent in an ambiguous community in late antiquity known as “God fearers” (yirei shamayim) who lived and even practiced some form of Judaism as non-Jews. In this community, as Harvard’s Shaye Cohen notes in The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties, they were “gentiles who were conspicuously friendly to Jews, who practiced the rituals of the Jews, who venerated the God of the Jews, denying or ignoring all other gods –- these gentiles had an unusual attachment to Judaism, were sometimes called ‘Jews’ by other gentiles, and may have even thought of themselves as ‘Jews’ to one degree or another”.

Schachter-Shalomi calls these modern-day “God fearers” “psycho-semitic gentiles,” individuals who feel close to Judaism but for a variety of reasons do not want to become Jews, at least not yet. Many want to retain dual membership in numerous faith communities (like many Jews) that formal conversion would preclude. There is exclusivity in conversion that many spiritual seekers today feel uncomfortable embracing. In time, some of these psycho-semites may choose conversion. Some will not. But those who do convert will do so from a deep internal commitment of their own making and not as a solution to the problem of collective Jewish guilt.

Making Space for the Psycho-Semite: An Alternative to Eisen

What I am suggesting as an alternative to Eisen’s “making converts” is that we can respond to the reality of intermarriage by making space; physically, liturgically, and ritualistically, for the new ger toshav, God fearer, or psycho-semite. There are many non-Jews in our midst, in our schools and in our beds, who want to partake of our tradition as non-Jews with deep conviction (kavvanah) and a whole heart (lev shalem). To do that we would need to think creatively about liturgy and ritual inclusion, about ways these individuals could feel integrally a part of the Jewish spiritual community while retaining a status that is not fully “Jewish.”

The reality of postethnicity and intermarriage may yield an American Jewish community that is no longer comprised solely of Jews. It already has. According to scholars such as Shaye Cohen, this may not be the first time in history this has happened (we do not have accurate intermarriage rates in late antiquity and medieval Spain, but intermarriage appears to have been more prevalent than we think). The context of Imperial Rome and medieval Spain was certainly different than contemporary America, but the problems Jews faced in regards to non-Jews in their midst may be similar. In a relatively open society, non-Jews will find Jews, and Judaism, attractive. I think that is good for society in general, for Jews, and for Judaism. Our challenge may be finding creative ways of cultivating that attraction while maintaining a sense of difference.

Conversion is one method. I would suggest it is quite a radical choice, too radical to be used as a means to an end. It may not be, should not be, for everyone, and certainly not be a response to pressure, overt or subliminal, but solely generated by an inner calling. For example, what if a non-Jewish couple came to a rabbi and one of them was intently committed to converting to Judaism? Some rabbis would say, “I am not in the business of creating intermarriages.” I would say, “If that is your calling, if it comes from deep within, I will help you along that path.” Conversion should be an individual and not a relational choice.

Arnold Eisen’s program bravely confronts intermarriage, a contemporary Jewish dilemma that we used to call a dangerous Jewish problem. He offers one solution, I am offering another. This is all part of an important conversation that should include many voices from the variegated spectrum of American Jewry.

Shaul Magid is the Jay and Jeannie Schottenstein Professor of Jewish Studies and professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University/Bloomington. His most recent book is American Post-Judaism: Identity and Renewal in a Postethnic Society (Indiana University Press, 2013). His forthcoming book, Hasidism Incarnate: Hasidism, Christianity, and the Construction of Modern Judaism (Stanford University Press) will appear in November 2014.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

- We're on Hiatus!

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats