Afterthoughts: Making Memory Matter after the Ferguson Weekend of Resistance & Sukkot

The leaders of one of the youth-led collectives in Ferguson, Millennial Activists United, have a ritual that they do before each protest, and when I first witnessed it during my five days as a rabbinical student in solidarity with them during the Ferguson Weekend of Resistance, it moved me to tears.

They huddle together, and as they chant and repeat, they begin to jump up and down, often hugging each other with one arm with the other raised in a fist, as if transferring to each other courage for the night ahead. They jump and hug and their voices rise as they yell this directive from Assata Shakur of Black Panther fame, words that have resonated with protestors across recent movements, from racial justice to queer liberation: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

That first time I saw them do this, it was my first night back in St. Louis, my hometown, a place I had been longing to return to ever since August 9, 2014, when Michael Brown was killed and St. Louis became a fixture in the national news. It was a Thursday, two months after Michael Brown was shot and left in the street for 4 hours and 32 minutes.

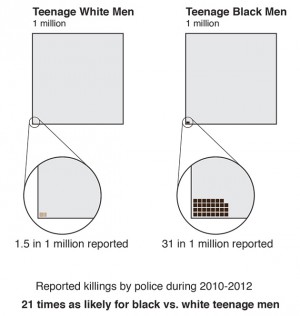

I was one of thousands who had come in answer to Ferguson October’s call to join in solidarity with a Weekend of Resistance, called by the cry “this is our Freedom Summer.”. I came to support those working to make my city better. I came to participate in a clergy march meant to raise the national profile of the movements for racial justice and against the criminalization of people of color. And I came as an ally. I came as a white member of a multiracial family in a country where a black man is 21 times more likely to be killed by the police than a white man. Yet, I could never have expected that when I arrived home to my old neighborhood, Shaw, I’d find that it was also in a protest akin to Ferguson’s, this one inspired by another police-involved shooting that had killed another black teenager, Vonderrit Myers Jr., on the previous evening.

ProPublica, Jonathan Stray

“I came as a white member of a multiracial family in a country where a black man is 21 times more likely to be killed by the police than a white man.”

October 10 was also the second night of Sukkot. I had not had a chance to shake the lulav that day, but as I walked down my old streets, and the chants filled my ears I knew immediately that this would be one of the most important observances of Sukkot I would ever make. Because Sukkot and Passover are far apart in the Jewish calendar, it is easy for us to forget that Sukkot is a story about “losing our chains,” but indeed, Sukkot and its rituals are about what happens after the Exodus. Sukkot is a week about how we lived after escaping oppression.

That night in Shaw, I saw the oppression more clearly than I ever have. I walked for hours and learned what wandering means. That night in Shaw, the St. Louis City police showed up to a memorial march in riot gear, just as the Ferguson Police Department had done. In my own neighborhood, marching as the Constitution says we can, I saw so many peaceful protestors met with police brutality.

I ran as a police officer threatened to mace me if I didn’t move from the sidewalk. I walked backward down the street and watched the cloud of mace rise in the air and heard the shooting of rubber bullets and the screams of those who were shot. As we slowly backed down Grand Avenue, bordering a park we had wandered countless times, there were so many moments when I longed to jump between my black husband and police who seemed programmed to see him as threatening and inclined to move him with force, leaning toward him and gripping their holsters even though his hands were up and he was yelling “I am a human being!” I did not jump though, but just walked, my hands in the air, staring at that cloud and praying silently for a sukkah to descend for our protection.

Alex Sievert

Sarah Barasch-Hagans and Graie Barasch-Hagans in Missouri during the Ferguson Weekend of Resistance.

The second night of Sukkot, I did not sleep. Instead, I lay awake, wondering how I could possibly continue to protest now that I had seen what it would take. I had come here thinking I could take part in building a sukkat shalomecha, a shelter of peace, to help rebuild St. Louis. However, over the next several days, it would become clear that it was the Ferguson leaders who were teaching me the true meaning of Sukkot – that fear cannot protect us in a world that has never been safe enough, and that we cannot count on permanent structures to save us. The sukkah is built in ways that give us who are secure in our modern lives a taste of how impermanence and danger might feel – with a roof that has enough space through which to see the stars and in the commandment that we sleep in them. The lesson of Ferguson October is that our structures protect only some of us, while leaving many others to march.

The metaphor of marching toward the promised land came in full focus on Moral Monday on October 13, during which the leadership “shut down St. Louis” through a series of public actions, including disrupting, among others, the Ferguson Police Department, Emerson Electric, St. Louis City Hall, St. Louis University, a suburban luxury mall, a Rams Game, three Walmarts, and fundraisers for candidates for US Senate and County Executive. Like the ancient Israelites, the protestors packed light and traveled through a hostile land, tweeting their next location while they were already carpooling. They mobilized and shifted quickly and effectively to stage protest after protest, bringing their message to a public that could no longer pretend that Ferguson was far way.

That Monday night, as I joined them in a Walmart parking lot just feet away from humans holstered with mace and clubs, I suddenly realized that I no longer felt fear. I felt protected by love of which the protestors sing: “Revolutionary love, love, love…. I love my brothers, my sisters, my chosen family.” The chanting was making me feel safe, even amid the police in their riot gear, so safe I could imagine summoning all of my courage to continue to march through this desert. I looked up and could see the stars and I knew that my residency in this sukkah would need to be much longer than seven days.

As I chanted along with the leaders, “We young, we strong, we marching all night long,” I remembered that remembering is holy, but only if the remembering leads us to a better reality. I knew that during this Sukkot we needed to remember Michael Brown so that future years could be spent changing hearts and minds and policies. And in that moment I knew that the fight will take a long time, but that it is built on love, and that is why it will win. As we chanted again of “marching all night long,” I thanked God that, though this world is full of terrible injustice, there is also a tribe sheltering each other, in chosen families both fragile and strong, hugging and jumping all night as they march away from their chains.

Sarah Barasch-Hagans is a second-year rabbinical student who is from St. Louis. Before moving to Philadelphia to begin her studies at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, Sarah lived in New Orleans, where she was a founding member of Jews Pursuing Justice. In addition to interning for Ritualwell.org, she is the rabbinic intern for T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights on its campaign to end mass incarceration. Sarah is married to Graie Barasch-Hagans, an education justice activist and fellow St. Louisan.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Sarah Barasch-Hagans

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!