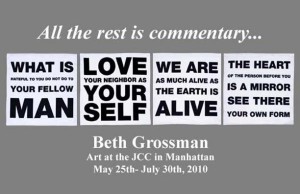

Twelve Bites of the Apple: Beth Grossman’s "All the Rest is Commentary"

This essay was inspired by an exhibit by artist Beth Grossman, presented from May 26 through July 30, 2010, at the Laurie M. Tisch Gallery at The Jewish Community Center in Manhattan. The main element of “All the Rest is Commentary” is a series of table cloths based on variations of the Golden Rule collected from twelve world religions. The project includes several “Table Talk” participatory performance art events, in which visitors join the artist at table to consider social issues in the context of the Golden Rule. My method has been to invite the texts—and the images and ideas they evoke—to dance through my mind and heart. I hope every reader and viewer will do likewise.

1) “What is hateful to you, do not to your fellow man. This is the law: all the rest is commentary.” Judaism

Whenever I hear the words “Golden Rule,” an image arises in my mind of a polished golden apple, its satiny perfection suspended in a luminous white space.

Until I began to write this essay, I never asked myself why. The answer that comes to me now turns on the Golden Rule’s perfection: its elegant simplicity, the way it occupies a central space in nearly all spiritual traditions, a universal tongue sliding into a universal groove. Like the apple of knowledge of good and evil in Genesis, it encapsulates the life of meaning: the search for balance between our animal and higher natures, the lifelong sequence of acceptances and refusals that comprise the human project.

2) “We affirm and promote respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” Unitarianism

In Deuteronomy, and in Psalms, Proverbs, and Lamentations, the Hebrew bible’s references to the pupil of the eye are almost always translated as “the apple” of the eye, symbolizing what is most precious, most in need of safeguarding. “Keep me as the apple of the eye, hide me under the shadow of thy wings,” reads Psalms 17:8.

Literally, though, the Hebrew text reads “bat ayin,” “daughter of the eye,” greatly resembling the English word’s Latin original, pupilla, a diminutive for child. Why? When we gaze into another’s eyes, the etymologists say, we see our own image in miniature reflected there. The Golden Rule is inscribed in the apple of each person’s eye.

3) “”The heart of the person before you is a mirror. See there your own form.” Shinto

The Golden Rule governs the creation of community, and also the creation of art. Its realization requires the two skills that make both possible: imagination and empathy.

To apply the Golden Rule, we must be able to put ourselves in the other’s place and to imagine how a sensibility very different from our own might perceive the actions we are about to take. Its precondition is awareness of our own feelings: how else are we to know what may be pleasing or hateful to ourselves? And that awareness must be matched with the ability to imagine the other’s feelings as if they were our own, as described in the Shinto text Beth Grossman has chosen: “The heart of the person before you is a mirror; see there your own form.”

The skills of imaginative empathy can be learned more fully through engaging with art than by any other means. In the realm of art, we rehearse for the challenges life may bring. We find commonalities even while recognizing differences. When as creators or participants in a work of art, we are touched, astounded, transported by what we experience, we glimpse something that can never be fully expressed. We bring that experience of the ineffable into our next encounter, into the pleasure of trying to represent the inexpressable, over and over again. When we make art, when we make beauty and meaning, we bring all four worlds of experience—body, emotions, mind and spirit—into focus. In the full flow of creativity, we experience that unity to which spiritual practice aspires.

4) “Blessed is he who preferreth his brother before himself.” Baha’i

Our desire to create and tell stories, to share beauty and meaning, is as powerful as thirst in the desert. When we mourn or celebrate, we raise our voices in song, understanding that ordinary speech and mundane acts do not suffice to contain the desire for connection these moments confer. We dance in triumph, or to prepare ourselves for a new challenge. Making art is as intrinsic to human life as breathing. Whether through music, dance, drama, of the creation of visual imagery, we make art to understand our feelings, to mark important moments, to reach out for connection. No matter how great the obstacles, we make art to endure and to assert our humanity. Under the most terrible conceivable conditions: in concentration camps and solitary-confinement prisons, people scrape up bits of mud or hoard bread or save charcoal to make their mark on experience. Every time we make art, we build the muscles of imagination and empathy without which neither community nor compassion would be possible.

Every holy book embeds its teachings in a story of creation, a narrative that shapes and ennobles human purpose, urging human beings toward the moral grandeur that is our highest realization. The stories magnify the teachings, creating entry-points into our own lives. Whether, as indivduals, we have brought this truth to conscious awareness or not, human beings know that the way we tell our stories shapes our lives.

5) “We are as much alive as the Earth is alive.” Native American

As we have been learning from the work of neuroscientists, the structures of our brains, and therefore our habits of perception and thought, were formed a very long time ago, when early humans roamed the savannah in hope of finding (rather than becoming) prey. We humans are very good at noticing danger, movement, and difference, skills that contributed to our ancestors’ survival. This early conditioning inculcated the habit of protecting and pursuing the interests of our own bands or tribes, and that meant fearing others, or at least keeping them other.

We make sense of visual stimuli by sorting through templates stored in our minds, matching them to the evidence of our eyes. Have you ever had the experience of walking in the woods and seeing a deer that as you approach turns into a fallen log? At every intermediate step between the perception deer and the realization log, the mind tries on templates, seeking the best fit.

Seeing in categories, we easily generalize about huge numbers of our fellow beings. In human relationship, the categories “us” and “other” are extremely powerful. If we let the oldest parts of our brains work without the contradiction that originates in conscious thought, we may endow the category of “other” with less dignity, less value, even less claim on life than we give our own kind.

6) “In happiness and suffering, in joy and grief, we should regard all creatures as we regard our own self.” Jainism

Our brains’ limbic systems are stocked with chemicals that encourage and enable swift reaction for aggression or defense. All of us have glimpsed a shadowly figure turning onto a dark street: our hearts pound, a chemical surge overtakes us as the fight-or-flight reaction is triggered. Our basic human equipment is just as reactive today as thousands of years ago. But if we behave as our ancestors did—bash it or dash it—we are likely to be arrested.

For the long sweep of recorded history, spiritual teachings have stressed the Golden Rule as an antidote to our innate reactivity and the damage it can do. It introduces choice in the place of compulsion. It helps to bridge the distance between ourselves and the other. It is the essential building-block of human development, the balm that cools our tempers, the advocate for the neocortex against the powerful impulses of the limbic brain. The Golden Rule is a mnemonic. Committed to memory by countless repetitions, it issues regular reminders that the shadows we perceive may originate in our own minds. “In happiness and suffering, in joy and grief,” reads the text from Vardhamana, founder of Jainism, “we should regard all creatures as we regard our own self.”

7) “Don’t create enmity with anyone as God is within everyone.” Sikhism

Scientists have lately detected the presence of an “empathy gene,” a receptor gene for the hormone oxytocin, which promotes social interaction and the formation of bonds of friendship and love. Neuroscientists also have found “mirror neurons” in the human brain. When we observe someone else (or imagine ourselves) experiencing a feeling or performing an action, these nerve cells are activated very much as if we had performed the same actions with our own bodies. In this way, motor neurons are thought to aid our understanding of other people’s perceptions, actions, and feelings.

But while the capacity for empathy is encoded in our physical beings, imaginative empathy does not automatically infuse our own life-choices. We must learn to move from the feeling to the practice of compassion. In this project, Beth Grossman has presented a dozen variations on the Golden Rule that are actually several dozens in layered form. Each text offers a complete teaching on its topmost or outer layer, as well as additional teachings embedded in the artist’s typographic and design choices. The embedded teachings pose profound questions opening paths of self-exploration. What does it mean to “LOVE YOUR SELF”? What does it mean to “REGARD AS WE”? Through this multiplicity, engaging with “All the Rest is Commentary” offers a singular question to each person, an essential question underpinning compassion in action: “What does the Golden Rule mean to me?”

8) “A state that is not pleasing or delightful to me, how could I inflict that upon another?” Buddhist.

Of all the formulations of the Golden Rule, my favorite is the one attributed to Rabbi Hillel, giving Beth Grossman’s wonderfully conceived project its title. It happens to be almost identical with the Sanskrit text she has selected from the Mahabharata, the vast epic that, along with the Ramayana, provides the Hindu historic narrative: “This is the sum of duty; do naught onto others what you would not have them do unto you.” The Talmud relates that Hillel, who was born in Babylon 2000 years ago, was challenged to explain the whole of the Torah to a non-Jew during the space of time the man could stand on one foot. Hillel said: “What is hateful to you, do not do to others. This is the whole Torah. All the rest is commentary; now, go and learn.”

I like this version best because its underlying message is to refrain from harm. For me, it carries less risk of foisting unwanted—however well-intended—attention on others. For example, I’ve found myself in debate with people of other faiths who apparently see no violation of the Golden Rule in attempting to persuade me at length that since they love their own religious practice, I ought to adopt it too.

Hillel’s Golden Rule turns on the commonsense expectation that whatever we find painful or distasteful ought not to be inflicted on others. We can’t be certain of another’s deepest desires without knowing that person very well indeed, but it seems reasonable to expect that even strangers will not want to be harmed.

In recognizing the truth of our simultaneous difference and similarity, Hillel’s dictum incorporates the understanding that human beings have varied ways of seeing. This ought to be obvious, perhaps, but often, it is not. How many arguments end in frustration as one or both conflicting parties fail to understand why, having explained so clearly a particular way of seeing a situation, the other party persists in holding to a view that is obviously incorrect?

No doubt, many of us can recall that moment of passage toward maturity that is marked by the realization that other people are not necessarily stupid or crazy because their perceptions differ from our own. The wish to reserve to ourselves the right to differ seems universal. Hence the Golden Rule as stated in Theravada Buddhism: “A state that is not pleasing or delightful to me, how could I inflict that upon another?”

9) “One going to take a pointed stick to pinch a baby bird should first try it on himself to feel how it hurts.” Yoruba

I appreciate how the twelve selected ways of looking at the Golden Rule Beth Grossman has chosen encapsulate in form as well as content this recognition of difference. By showing how very different words and images can contain the same teaching, each one offers a double lesson in imagination and empathy.

“One going to take a pointed stick to pinch a baby bird should first try it on himself to see how it feels.” This is not merely a Yoruba proverb, it’s a panorama: I see the stick, the nest, the fledgling, the adventurous child spilling with curiosity like an over-filled cup. Then I see the second statement embedded in the text: “One should first try it on.” I imagine stepping into another’s body and feelings as if they were a suit of clothes. Trying it on: I understand that this as the preliminary step, the practice of imaginative empathy, that transforms our actions, enabling them to be the product of choice rather than compulsion.

I imagine myself taking part in one of the Table Talks Beth Grossman conceived as part of “All the Rest is Commentary.” “Did you try it on first?” I imagine one of my conversation-partners asking, but instead of a sweater or a pair of pants, the subject is compassion.

10) “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Christianity

The first reference to the apple of the eye in Torah is in Deuteronomy 32, in Moses’ parting words to the Israelites. On the occasion of his 120th birthday, Moses takes leave of the people, anointing Joshua as his successor, and speaking his last as God’s messenger. He portrays a loving Father, deeply disappointed by the self-regard and disloyalty of His children, who warns of the punishments that will follow further betrayal. The imperative to “love your neighbor as yourself” has already appeared two books earlier, in Leviticus 19. By the time the story is repeated in Deuteronomy, it has become clear that we will ignore the Golden Rule as often as we honor it. Even the rule’s Author knows that human beings will fail to follow it, yet persists in asking, urging, commanding, and threatening in the hope of a different outcome.

Sitting across from each other at tables covered in the words of the Golden Rule, each individual who participates in a Table Talk will carry a lifetime of skepticism about the prospect that humankind will begin living by the Golden Rule, and a lifetime of the will to keep trying.

11) “This is the sum of duty; do naught onto others what you would not have them do unto you.” Hinduism

Part of the Golden Rule’s perfection is the way it applies equally to the smallest human encounters and to the most complex and sustained. The loving parent bends toward the errant child to ask, “How would you feel if someone did that to you?” Just so, I would be satisfied with the Golden Rule governing virtually all public actions. Consider this: how would things change if we required policymakers and their loved ones to live under the precise terms and conditions they describe for those less powerful or fortunate than themselves?

This would dramatically reduce war-making; raise the quality of public housing, education, and healthcare; curtail the national obsession with punishment that has made us Incarceration Nation, with the largest prison population and highest incarceration rate on the planet; bring about a living wage. What could it not accomplish?

12) “None of you is a believer until he desires for his brother what he desires for himself.” Islam

“All the rest is commentary.” The Golden Rule is the DNA of morality, the seed that sprouts the tree of life. “None of you is a believer until he desires for his brother what he desires for himself”: this is one of the teachings of the prophet Mohammed collected in the volume known as Al-Nawawi’s Forty Hadith. It expresses the underlying religious assertion of the Golden Rule, that in divine sight, each human soul is equally deserving because every life originates equally in a divine spark. Yet the Golden Rule’s existence is not supported by religion alone. Even for the most secular relativist, it is necessary, because the alternative—perpetual license to treat others as lesser beings or even as objects—is unthinkable, creating a state the philosopher Thomas Hobbes described as “bellum omnium contra omnes,” the war of all against all.

In the ordinary course of life, our attention is drawn to those times the Golden Rule is forgotten, ignored, or flouted. Follow the news, and these breaches multiply like feathers bursting from a torn pillow. But in truth, the Golden Rule is honored far more often than breached, in countless small kindnesses and everyday gestures of caring. Considered one at a time, most human beings are ordinarily good-hearted—not heroic, always, but decent, each heart, encasing the sweetness of a golden apple, beating in time to our hopes.

The orchard withers when empathy and imagination are withheld, when we lose track of our own role in collective actions. If you or I really felt the fullness of individual responsibility, how many of us would knowingly make those choices that have brought such shame and pain to our collective soul? Expressing art’s highest intentions, “All the Rest is Commentary” is offered to engage precisely that question, to collapse the distance between me and we.

A dozen golden apples are piled on a plate: let all who are hungry come and eat.

#

Beth Grossman’s exhibit, All the Rest is Commentary, will be on view May 26 through July 30, 2010 in the lobby of The Jewish Community Center in Manhattan. The JCC in Manhattan is located at 334 Amsterdam Avenue at West 76th Street.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Arlene Goldbard

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?