Interview with Andrew Ramer: Sex, Jews, and Queer Midrash

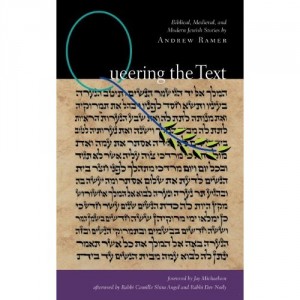

Andrew Ramer is a midrashist, novelist, body worker, and spiritual teacher. His work ranges from a book on angels,Ask your Angels, Ballantine, 1992, to pieces of gay erotica: see Best Gay Erotica 2001. His most lasting contribution, however, may well be his work in gay spirituality. Ramer writes a regular column on spiritual practice for White Crane Journal, and is the author of gay Jewish prayers and blessings used widely in the Jewish lgbt world and collected in Siddur Sha’ar Zaha. I sat down with Andrew Ramer just before Pride weekend in San Francisco to discuss his new compilation of Jewish midrash, Queering the Text: Biblical, Medieval, and Modern Jewish Stories –Jo Ellen Green Kaiser

ZEEK: Readers are becoming accustomed to the idea that there may be gay figures in the Bible, like David and Jonathan. But your midrashim go way beyond that.

Ramer: I am using characters who are all bi. In those letters, LGBT, the “B” is usually lower-cased, the least expressed. Yet in some ways, in terms of human nature, it’s the most common. It’s the stepchild of the movement. What I’m struggling for is a universality of queerness, across the spectrum.

ZEEK: Give me an example.

Ramer: Take the example of David and Jonathan. Jonathan has a wife and many children. David has, what, 8 wives?

ZEEK: He is king, after all.

Ramer: Yes, he’s the alpha male. If he had other male lovers, we don’t know about them. Those stories weren’t preserved. Often what gets preserved is tragedy. In the story of Dinah, the only thing we know about her is her relationship with a man [described as rape], but I play with one little line, about her going off with a woman. I use that as a door to queerness.

If we can say with audacity that what somebody writes now is Torah, then if we look at the Torah that is written and the Torah that I have created, Dinah is a person with a rich physical life. I wander in what little territory we have.

ZEEK: It’s often said that Judaism is unique among Western religions in being joyful about sex and sexuality. Your midrashim show us how little of that eroticism really is in traditional texts; you expand out the erotic moment.

Ramer: There are things that we say about ourselves as Jews that are not true. That is one of them. I have friends who are Muslim who think that Islam is way more sex-affirming than Judaism. There are fewer prohibitions in Islam on when and what and where and how. In the Koran, there is more of a sense of physical joy.

What you said about sex reminds me of the way Jews say, “We do death well.” I think it’s emotionally vital, unless a body is hideously damaged, that people see dead bodies. I think Judaism does death really badly because we disguise it and I don’t think that’s healthy. Maybe the people in the chevra kadisha do death well, but for the rest of us, not to see the body, I think that’s a big mistake.

ZEEK: To get back to sex, I think of the way some Orthodox do sex, they cover up completely.

Ramer: Yes, so, some of what we say is not true. Lurking in that idea about sexuality is something else. We don’t even have a word for Jewish anti-Christianism. But we have a word for Christian anti-Semitism.

Sometimes when we say, “we do sex well,” what we mean is that we do sex better than the goyim, better than the Christians. “We do death well” means that we do it better than them. I wander into these places all the time. But maybe this discussion isn’t part of the book discussion.

ZEEK: It is, because the setting of the middle section of your book is El-Andalus, a place and time we think of as the coming together of Christian, Muslim and Jewish culture. In your book, there are erotic and spiritual engagements between the three peoples.

Ramer: Yes, this middle part of the book is the only part about male-male relationships. They are intergenerational, interethnic. It’s the heart of the book for me. Perhaps this is the appropriate place for the disclosure that I can’t write about lesbians or trans people from my heart in the same way [as I can write about gay men].

There are heartbreaks in those stories, they are not all joyous. The section ends with a story after the expulsion. The second to the last story is joyous though. It’s set in an Andalus that is also San Francisco at the time when gays could get married here [2005]. My second disclaimer is that my Andalus is like Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado: entirely imaginary and completely a reflection of my own experience, my own time and place.

ZEEK: Why did you choose to do an imaginary Sephardic Spain instead of modern-day San Francisco for your midrash?

Ramer: I was captivated by the poems. There are real medieval poems written by famous rabbis whose names we know, whose liturgy we use, Ibn Gavriol, for example: these rabbis were writing erotic poems to young men. There’s nothing else I know of like that in Jewish history.

In the biblical period, I had to make things up from little hints—it is possible to read David and Jonathan as I was taught in Hebrew school, as the story of good friends. And maybe it’s sad that we’ve become so sexually focused that we have lost the incredibly deep love, as friends, that two men or two women can have for each other. There is a tragedy in that. I remember pictures of my father and his best friends with their arms around each other, in a way that is physically much more awkward for men of my generation–hetero, homo, or bi–to do.

The Andalusian poems are intergenerational, which is problematic for the sexual politics of the twenty-first century and our ideas about consensual relationships between adults. The poems the rabbis wrote are about men and young men. But we don’t have anything else like that. I was going to say, I wanted to honor the poems, but really, I’ve been reading them and wanted more, I wanted to get inside them in a different way.

ZEEK: Your book is structured in three parts, with the first set of midrash set in biblical times, a second set of stories set in medieval Spain, and finally, four stories set in the present. The four midrash in the last section are organized under the rubric of prayer, with the stories labeled Shacharit, Musaf, Mincha and Maariv, a full day of worship. Can you explain what your thinking was in doing that?

Ramer: I don’t know. I think a lot, but sometimes I’m just following a creative impulse. Originally, there were just three stories there. I added Musaf later, even though it was a story I had actually written earlier.

One reason I thought of the prayer service is because the first section of the book, the biblical section, has 22 stories in it, one for each letter of the [Hebrew] alphabet. I liked the notion that the beginning and end would be anchored in some kind of Jewish experience, alphabet and prayer. It’s a literary conceit.

ZEEK: The last section is the most curious. All four pieces are framed as real stories, as an interview, a transcript. If they weren’t in this book, some people would think that these things had really happened, and didn’t have anything to you as a writer.

Ramer: Yes. A very good friend who read the last story (about Bedouins) said, I didn’t know your Hebrew was good enough to translate that. And I said, thank you, but the whole thing is fictional, including the preface which says this is a translation.

ZEEK: Why did you end up putting these three different sections together?

Ramer: It’s a primer. It’s a primer for how to see Jewish experience through a queer lens.

My only regret is that I’d written another section, placed in the Hellenistic world. Jews were wandering in and out of Greek culture, and must have been exposed to a whole different morality, to homosexuality. I have no evidence there was homosexuality in the Jewish world then, though of course there always is, but I would have liked imagining that period.

You could say that all of my stories take place in what I would call parallel realities.

ZEEK: Do you ever feel like you are living in a parallel reality?

Ramer: Parallel to the one I grew up in? Yes. When I was a child, I had recurring dreams of a parallel family. In the family I am from in this reality, my mother’s mother had two brothers and two sisters, and an older sister who died at age two. In the dream world, almost everything was the same except that my grandmother’s older sister didn’t die, and she didn’t have a younger brother. In my dream life, I watched this parallel version of my family unfold, and they were having a much better time. Having an older sister changed my grandma’s life. I would wake up in the morning and wonder, “Why did I wake up in this reality, instead of in that reality?”

I’ll tell you when I finally understood this recurring dream. One day, in the 1970s, I was taking the ferry to Fire Island. Two men in a little speedboat were coming perpendicular to our path. I was the only person watching, because everyone else was on the other side of the ferry, staring at dolphins, I think. Anyway, I was the only person watching, and I and the two men were staring at each other. It looked like they were going to crash right into us. Some macho thing.

They sped up, and made it. Shooting behind their boat was this enormous wake. Then, the strangest thing happened. As the ferry crossed the wake, the whole wake moved, so it went from being perpendicular to the ferry to being parallel to the ferry.

In that moment, everyone on the ferry turned around. They were all puzzled, to see this wake parallel to the boat. But I had seen it. I stood there and thought: this is what happened to me in my dreams. I was in one reality, and then I was in another one.

My book also is based in a parallel reality. That’s where I live.

ZEEK: Is that what queerness means to you?

Ramer: Yes. I have friends who are in heterosexual marriages who are queer, who have a queer sensibility. It’s easier to have that sensibility if you are trans, or bi, or lesbian or gay, or if you are an artist or creator, because you are tapped into a primal energy which is more chaotic.

ZEEK: Some people would assume, from your title, that your aim is to bring queer people into the tradition, and others would think that it’s to make the tradition strange, or queer.

Ramer: Both. The cover of the book is from Esther. My midrash about Esther is all about being in disguise, and how it plays out for people who have to be in the closet. But the Pride march is coming, and people who don’t have to live closeted lives will appear in every manner of costume, disguise, drag, self-revelation, genderfuck—and I think that is what I do as a writer. I wander in and out of reality.

In the afterword to my book, Rabbis Camille Angel and Dev Noily quote Elie Wiesel saying, “Some events do take place and are not true. Others are, although they have never ocurred.” That is my dream, that has colored my life, being where different realities start and stop.

The original title of the book was the Genizah of Dreams, which ended up being the title of the first section. A genizah is a repository of books. In the Jewish tradition, you can’t destroy a book if it has God’s name in it, you have to put the book in a repository. There are several famous genizahs that have incredible archives of things that would otherwise be lost.

The genizah of dreams is where I live. I take information from the collective and weave it into a shared narrative. My hope is that we will all find a way to bring some material back from the genizah of dreams to enter the common dialogue. The boundaries between queer and non-queer dreams can become increasingly permeable once they are brought together in the genizah. That is the hope of the world, that you can have a really diverse and paradoxically at the same time a unified culture, that all human beings on the planet can share.

ZEEK: Thank you.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Jo Ellen Green Kaiser

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats