Appeals to the Outcast: The Bowls Project

What am I to do (for my child with six toes)?

Jewlia Eisenberg, leader of Charming Hostess, is telling me about her new project inspired by the incantation bowls of Babylonian Jewish women of Late Antiquity.

“They’re very practical, requests for the home, but at the same time, they’re really out there and crazy. Like, ‘let the angel of pleasure, Dilibat, be watching over the children of Hamdu.’ It’s like, the angel of pleasure? Jews have an angel of pleasure? I’ve never heard of Dilibat, you know? Well, it turns out Dilibat is Ishtar. She’s a loan from the Mesopotamian pantheon. It’s porous, you know? These characters are floating. They float between the Jewish bowls and the non-Jewish bowls.”

The Bowls Project – as it’s simply called – encompasses an album, an interactive installation piece, and a curated series of music and “radical ritual” taking place at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in a structure made for this purpose. The project is inspired by this particular form of protective magic – actual bowls inscribed with spells or curses and buried in the ground – that were common in Babylonia about a millennia and half ago. Jewlia has done workshop versions of the project during residencies at the Headlands Center for the Arts and at the University of Denver. She tells me that she knew she wanted to make a space “that echoed the physical bowl and a space that felt intimate, like the concerns that were inside of the bowls.” She has recruited a team of at least twenty (she lost count) architects, structural engineers, and contractors to build the installation/performance space in the sculpture garden at Yerba Buena.

In your name, O Lord of heaven and earth. Appointed is this bowl to the account of Anur … bar Parkoi, that he be inflamed and kindled and burn after Ahath bath Nebazak. Amen. … In the name of the angel Rahmiel and in the name of Dilibat the passionate, … the gods, the lords of the mysteries. Amen, Amen.

The idea for the bowl-like space that will house the installation and performance area came together when she met an experimental architect, Michael Ramage. “He’s interested in timbrel-vaulted domes. They’re also called cohesive construction domes. It’s a kind of building where you lay these tiles in such a way so that they’re supported by their axial forces. So, for example, a Roman arch, it’s supported because the stones come together in the middle. That’s not what these do. These kind of, like, fly out by themselves,” she explains, waving her hands in the air.

The blend of concept, craft, and obscure texts has been the trademark of Jewlia’s work with Charming Hostess. Formed in Oakland in the mid-1990s, amid a world of punks, activists, and radical feminists reworking definitions of gender and identity, the band’s music hovers between playful provocation and earnest inquiry into heady multi-layered subjects. The professional vocal training of both Jewlia and Charming Hostess member Cynthia Taylor (who performed for ten years with the Oakland Opera), allows the conceptual aspect of the music to take flight. The band uses breathe and body sounds, constructing songs from doo-wop, a cappella, and beatbox, interspersed with the vocal heights of soul music and the spirit of folk ballads. Their albums have incorporated big band, Balkan, Bulgarian, klezmer-punk, and bluegrass influences, to name a few.

Charming Hostess celebrates everything creole, remixed, and cosmopolitan. Their music is consciously situated in the Jewish and African diasporic traditions. The women will sing in multiple languages, going out of their ways to learn the correct pronunciation of, say, Bosnian – or in the case of the Bowls Project, Aramaic.

The Bowls Project will come out in the Radical Jewish Culture series on John Zorn’s Tzadik label, the same series that saw the release of their most well-known works, Trilectic and Sarajevo Blues. (Four other albums – Eat, Thick, Punch, and Heavenshow – came out on other labels.) Trilectic is based on the diary of the literary theorist Walter Benjamin and recounts his relationship with his magnetic, polemical lover, Asja Lācis, the famous artist and Bolshevik. Sarajevo Blues is based on the book of the same name by Bosnian poet Semezdin Mehmedinovic describing the siege of Sarajevo in tragicomic detail. The same performative reinterpretation one finds in these albums is on display in the Bowls Project, translating text into music and song, bringing the long-buried words of anxious and hopeful women to life.

On Sunday, in the month of Av, I, Saluk Son of Hormizdukh, performed a magic act by the Name of I, Meshallah Son of Meshallah… It is buried in the threshold of the house of Saluk Son of Hormizdukh.

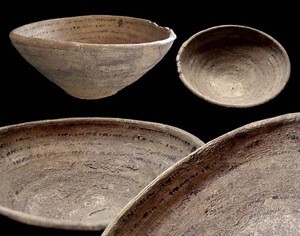

Incantation bowls, also called devil-trap bowls or demon bowls, were used as talismans in the area that is now Iraq and Iran from around the 6th to the 8th centuries. The bowls were inscribed with protective incantations and buried face down in the corners of people’s homes. They were thought to protect the individual who commissioned the bowl, who was explicitly mentioned by name. The incantations range from blessings for the family to curses of enemies to spells for love or fertility. They were written in the language of the time, Aramaic.

In the pre-Islamic Near East, supernatural beings were a familiar part of life. He Who Created the Heavens and Earth, and His host of heavenly angels, protected against demons and spirits such as the lowly but troublesome “pebbles-spirits” or infant-stealing liliths, among many others. These competing forces were subject to the spiritual technology of divine invocation through charms and amulets for the sake of everything from marital relations, neighborly gossip, and the quest for love. Like any tool, these had to be used properly in order to work. They required a skilled technician, a religious scribe.

The Jews were common practitioners of this form of protective magic. In fact, the proportion of bowls inscribed in Judeo-Aramaic, the Jewish dialect of the time, is higher than the percentage of Jews in the regional population. Judging by the names in these bowls, it’s clear that non-Jews commissioned Jewish scribes to write their bowls. The idea of professional Jewish magic may seem bizarre today but that is part of the allure of the Bowls Project, as is the position of the Jews in this diverse, multifocal cultural landscape. The incantation bowls attest to a surprising porosity and hybridity of religious identity and practice at the time. The unearthing of these bowls, beginning in the mid-19th century by British archeologists, is also the unearthing of a parallel history of Jewish practice, one that is not found in the canon of rabbinical literature.

“Angels and demons were popping up all the time in the bowls….but they’re not part of the Talmud, generally, or even Midrash, which has an ambivalent relationship to angels and devils because nothing is supposed to mitigate the power of the one God,” explains Jewlia.

“On the other hand, this part of our religious heritage doesn’t get repressed for a really long time. And while the Talmud is being written, and that ends up being the normative line of Jewish thought, this is what was the normative at the time. But we don’t pray to Delibat, the Goddess of Pleasure, to make an intercession for our sex life now.”

Suppressed are all demons, all no-good-ones, all pebble-spirits, and liliths, and mevakkaltas, and idols and goddesses… You are all suppressed by your names, whether their names are mentioned or are not mentioned.

The reconstruction of popular magical practices of Late Antiquity is accompanied by equally rare voices of women that have been excluded from the otherwise multi-layered discourse so well-documented in the Talmud and other Jewish canonical texts. This invitation into the home, into the personal fears and hopes of these women, fueled Jewlia’s fascination. She refers to this personal level of supernatural encounter as the “apocalyptic intimate.”

Jewlia discovered incantation bowls while perusing the personal library of UC Berkeley professor Daniel Boyarin, one of the foremost scholars on the Talmud. She took the book off the shelf, unable to resist the peculiar topic, and immediately found herself attracted to the content of the texts of the bowls. She was struck by the centrality of the issue of female intimacy in the texts, “how women relate to other women, how they relate to their children, to their daughters,” she explains. “A huge part of these bowls’ texts is female power, spirituality, and intimacy. Relations between women.”

“Daniel Boyarin was reading the Aramaic to me, out loud, so that when we sung, we would sing it correctly, and he stumbled over one of the words, and I was like, ‘What could you possible stumble over?‘ He was like, ‘It’s the ‘we’ form for women.’ The feminine ‘we’. It doesn’t appear once in the Talmud.”

The Bowls Project creates a channel into the intimate experience of these Babylonian women the same way Sarajevo Blues connected its listeners to the intimate experience of the siege of Sarajevo. At the same time, one of the many aims of the project is to assert women’s voices into Jewish religious discourse whose limits have historically been set by men. “All of our extent literature in this time and place is really about men. These bowls are talking about women constantly,” says Jewlia. Of course, the picture they paint is not simple. No awesome earth mother or comforting female deity emerge from the bowls, at least not at first glance. To the contrary, female supernatural beings are often threatening or demonic.

One of the most fascinating realities of the ancient world, which is played out in the bowls, is the transformation of gods and goddesses into evil spirits. As local deities lost their divine cache, either through military conquest or cultural drift, they often lingered in degraded form as dubious spirits or worse, as nefarious demons. Some scholars argue that this is the source of Lilith, the contentious female figure revived by postmodern feminists as a symbol of repressed and demonized female divinity. Lilith was considered a demonic threat to newborn babies as well as pregnant women and pubescent girls; she is a common presence in the bowls texts, often rendered in plural as the terrifying she-demons of the nights.

Jewlia tells me that the questions of how women experience female supernatural power, how they define and relate to it, are central to the Bowls Project. The questions remain open, allowing for space to explore the potential connections and poetic associations of these texts, searching for an authentic human experience behind it all.

Upon her head and upon the top of her hair he sealed his name: Barren one, we call you! This is the great name from which the angel of death flees. Amen, amen, selah.

Besides intellectual curiosity and artistic inspiration, there was also a political impetus to the project. Jewlia told me she developed the idea when the Iraq War seemed the most intractable and hopeless to her. She was hoping to counter the image of Iraq as distant, “other,” with the understanding that the place now called “Iraq” is the birthplace of civilization and as such, is part of our universal heritage. Granted, she tells me, laughing, her “little radical Jewish music album” is not going to make a big difference in ending the conflict there, but “it will go into the sea of people” who were opposed to the war from the beginning and have been making art against it all along.

Like the ambient associations that inspire the stylistic play of Charming Hostess, the political aspirations of the music are best understood on an associative level, in the fuzzy world of culture. The work withers somewhat in the harsh light of critical analysis but blossoms in the penumbra between intellectual curiosity and expressive subjectivity. That place between brainy and sensual, bookish and dreamy, is the fertile region where the band’s best work takes place. As with Sarajevo Blues, it’s the personal experience of an otherwise politicized situation that is the subject of the music. This is the “radical” component of the music, the production of what Jewlia calls “resistant culture.” In this vein, the Bowls Project is an attempt to assert these minor, suppressed narratives into the dominate religious tradition, contributing to a wider understanding of history and, by implication, creating room for a multi-vocal, inclusive culture of the present. “How do we dismantle imperialist culture? Well, by asserting our own culture,” Jewlia tells me, taking her cue from the Rastafarian idea of “singing down Babylon.”

For all the intellectual ambitions of the Bowls Project, like Sarajevo Blues and Trilectic, it is most successful as an expression of spirit. The explanations that frame the music remind me of the Hasidic custom of using a halachic or textual question to frame a drash that takes flight into imagination and storytelling. The underlying message is something nonverbal and intuitive. As our conversation drew to a close, I recalled how the Hebrew name for a demon, shad (שד), is derived from the name of an ancient Mesopotamian household protective god. Jewlia quickly pointed out how complicated the issue of power is, how good turns to evil and back again, and how we can see this in the evolution (or devolution) of female divinity, and how shad is, of course, connected El Shaddai, the name of God written on the most significant talisman to survive into our contemporary period, the mezuza, and is also the word for breasts, shadda’im (שדיים), another example of the whirlwind of language, ideas, and images that keeps the work of the Bowls Project afloat. “Culture,” vague and indefinable, may or may not save us. Either way, and whatever the motivation, the juxtapositions inspired by these ideas can give birth to art that is a pleasure to watch and listen to, to let resound and percolate in one’s mind.

This is the seal that is not broken, with which are sealed heaven and earth.

The structure at Yerba Buena is now under construction and will include a performance space and an installation piece featuring hanging microphones in which the visitor can speak anonymous “secrets of the home.”

Moving back into project manager mode, Jewlia tells me, “Now, all the drawings are in, and contractors are on board, and we have out-of-town architects, and we have architects here, and structural engineers, and all this stuff is happening pro bono.”

She shakes her head again in disbelief.

“The amount of people… I had no idea. No idea!”

A large-scale installation piece like this one is new territory for Jewlia, as is exhibiting in a major metropolitan art center. She tells me that she feels inexpressible gratitude for the team of people that have offered to help make the project possible. Charming Hostess is still fundraising to get the money to complete the structure. “Not only would this stuff not see the light of day, it would be like twenty feet under without the help of these guys, who give their time and energy.” They’re allowing the voices behind these bowls to see the light of day and for visitors to rediscover magic in our everyday lives.

The Bowls Project: Secrets of the Apocalyptic Intimate will run from Tuesday, July 6th through Sunday, August 22nd at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in the Sculpture Court at 3rd and Mission Streets. Opening night ceremony will take place on Tuesday, July 6th, from 6 to 8 p.m. You can obtain tickets here.

You can donate to the Bowls Project here. Or share a secret!

I seal and double-seal this article for Zeek Magazine, may it prosper and be read by many and spread insight among the sons of Yaakov, selah, and peace between the sons of Yitzchak and Yisma’el, amen, and in our land under our leader, may he be blessed on the path of justice, and may there be peace and prosperity in my community, with compassion towards the homeless and the stranger, may it be free of earthquakes and poison and budget cuts, let the demons of greed be vanquished and education be plentiful. I seal and double-seal, Yehudit Yonah Daughter of Esther Freidel, by these one-hundred-forty-two magical words with which they speak and listen, for the great hammer of splendor and the great axe of the beginning and scourge of the 360 pure pebble-spirits. Amen, amen, selah.

NOTE: The epigraphs throughout the text are from an incantation bowl from Nippur (Aramaic) (CBS 2972 – see Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur, by James Montgomery, p. 213, Museum Publications of the Babylonian Section 3. Philadelphia: University Museum. Go to http://www.schoyencollection.com/magical.htm); an incantation object from Sumer (MS 3033. Sumerian on clay, Sumer, 26th c. BC. Housed in The Schøyen Collection at University College London. Go to http://www.aakkl.helsinki.fi/melammu/database/gen_html/a0000563.php); an incantation bowl inscribed in Jewish-Aramaic (MS 2053/198, Jewish-Aramaic on clay, Near East, 5th-6th c., text translated by Professor Shaul Shaked. Go to http://www.schoyencollection.com/magical2.html); and “Oh Barren One,” from The Bowls Project, by Charming Hostess.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Joanna Steinhardt

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?