Review, "Telling Stories: Philip Guston's Later Works"

In 1968, after nearly two successful decades as an Abstract Expressionist, Philip Guston (born Goldstein) swashbuckled his way back into the realm of figurative painting. Not only was his subject matter shocking—his hooded figures bludgeon each other until they bleed, or sit in squalid rooms heaped with bottles, cigarettes, and halfeaten food—the execution of these works was equally crude. When Guston unveiled these paintings in 1970 at the Marlborough Gallery in New York, critics—and indeed most of his peers—were flabbergasted. In the words of Hilton Kramer, writing in The New York Times, Guston’s Marlborough show revealed “A Mandarin Pretending To Be a Stumblebum.” Rather than something which could be profitably smoothed away, however, the success of Guston’s late project hinged precisely on this calculated quality of clumsiness.

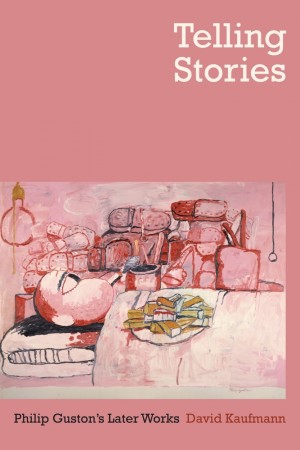

As David Kaufmann demonstrates in Telling Stories: Philip Guston’s Later Works (University of California, 2010), Guston’s deliberately retrograde style was in fact a complex response to tectonic shifts in the art world of the sixties and seventies. On the one hand, Guston’s late style was a slap in the face of Greenbergian aesthetics, which preached that a “process of selfpurification” was needed in order to uncover painting’s essence. But Guston’s lush brushstrokes were also a repudiation of the slick productions of Pop Art, often denuded of artistic touch. To those already familiar with Guston’s work, this broad schematization will not be a revelation. And to those who have read Dore Ashton, Ross Feld, or especially William Corbett’s memoir about Guston, Kaufmann’s book will not startle with a raft of new quotations or archival tidbits. The major contributions of Kaufmann’s slender monograph are more subtle and evaluative. What he does better than any other writer on Guston is to probe just what was at stake for the artist and his critics in his deviations from high modernism and—later on—the emerging dogmas of American postmodernism.

One of the curiosities of Guston’s reception is that despite being left for dead in 1970 by what Corbett called the “art world commissars,” by the mid-seventies he enjoyed a revival and even celebrity within certain circles. Kaufmann, quite correctly I think, pins this on a variety of factors, including a return to painting more generally and a dissatisfaction with the “high modernist vanguardism” (53) which Guston had skewered several years earlier. The stories Guston set out to tell in the latter half of the decade also changed. In his earlier paintings of buffoonish Klansmen—“Hoods” as he affectionately dubbed them—Guston meditated on the problem of “thoughtless evil” (45); a theme Kaufmann usefully explores through the lens of Hannah Arendt’s equally misunderstood reflections on “the banality of evil.” By the late seventies, however, Guston took an allegorical turn which struck a chord with viewers, many of whom saw striking parallels with the plays of Samuel Beckett. In Kaufman’s words, these paintings no longer groped after the sources of evil, “but concentrated on what it left in its wake: the individual body, suffering from desire, deterioration, and the threat of complete annihilation” (52).

If such works gripped critics in the years running up to Guston’s death in 1980—the same year of his last major retrospective until 2003—for the next two decades critical attention waned, even as these works continued to influence artists such as Georg Baselitz and Cecily Brown (a point largely ignored by Kaufmann). The dulling of Guston’s star in these years can be traced in large part, as Kaufmann successfully argues, to the blinding lights of postmodernism, with its infatuation with ironic detachment. While Guston’s works in the last years of his life are richly referential, recasting everything from the masters of the Quattrocento to Giorgio de Chirico, he was not so much dazzled by the possibilities of pastiche as haunted by the breakdown of tradition. As Kaufmann puts it, “Postmodern critics and theoreticians did not take up Guston’s work…because the sincerity of his ‘bad taste’ and his unfulfilled and unfulfillable nostalgia for transcendence rendered the allegorical nature of his later works unrecognizable…His allegories were marked by melancholy, not postmodern delirium” (69). If Guston has enjoyed an ascendancy in recent years, it is precisely because this febrile intoxication has dissipated. And here, of course, we also discover the primary legitimization for Kaufmann’s study, occasioned not so much by the discovery of new material on Guston as a changed historical moment, one in which “we no longer live under the sway of certain modernist or postmodernist assumptions” (69).

As timely as this discussion of Guston’s critical reception is, especially for specialists in art history, perhaps the most insightful—and certainly most entertaining—section of Kaufmann’s monograph is when he takes a slight detour to tell the story of Guston’s “Jewish Jokes” (71). Drawing analogies with figures ranging from Lenny Bruce to Philip Roth, Kaufmann makes the case that Guston’s deliberately crude style “signaled his awareness of the subterranean connection between assimilation and high art. His refusal of [modernist] decorum served a way of marking his work as Jewish” (81). As a theologian, I am inclined to see affinities between the pathos which Guston experienced in the face of a broken artistic tradition—an art-historical moment in which one could only “paint badly”—and a broken faith in Jewish tradition. But Kaufman’s correlation between the ‘bad manners’ of Guston’s painting and his counter-assimilationist impulse is an important story to tell, especially for an artist who has been too often typed as a self-hating Jew (pace Donald Kuspit).

If there is a disappointment in Kaufmann’s text, it is that he settles, in the final pages, on a rather pedestrian point: “It would…be impossible to be Guston again, though it will be difficult to avoid the general implications of his idiosyncratic path” (90). One of the great pleasures in Kaufmann’s text is the route he takes to get to this point, savoring the evident pleasure the author himself gets as he recounts the intertwining stories of Guston’s late paintings. As important as it is to read the signposts Kaufmann erects to Guston’s cultural landscape, perhaps the highest praise for this book is simply to say that bumping along to Kaufman’s easy prose feels a bit like taking a joy ride with a pack of Guston’s hoods, cruising along in a stolen jalopy, chomping on a stogie. And of course, listening to a story.

Aaron Rosen, PhD, is a fellow at the University of Oxford. His first book, Imagining Jewish Art: Encounters with the Masters in Chagall, Guston, and Kitaj, was published in 2009. He is currently at work on a new monograph entitled The Hospitality of Images: Modern Art and Interfaith Dialogue, as well as a children’s book entitled Drips, Zips, and Taxi Trips: How Modern Artists Get Their Inspiration.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?