Albert J. Winn's “Summer Joins the Past”

Summer camps offer brief encounters with utopia. Though usually located somewhere out in the wild, they are constructed, self contained domains, each fostering a worldview of its own. Dedicated to the collective living of an ideal existence, summer camps promote fantasy. Depending on which one they attend, campers can imagine themselves Olympic sports champions, Zionist pioneers, left-wing revolutionaries, master potters, or rock stars; the youth of urban ghettos can dream of leading a rustic life, rich kids can play at roughing it—at least for a few weeks. At the same time, camps have an underground culture that thrives alongside their various official agendas, from which campers learn how to cuss, gamble, smoke, drink, do drugs, or have sex.

Thanks, perhaps, to this complex amalgam of nature and artifice, adult ideals and adolescent secrets, summer camps have become a fixture of so many Americans’ lives. In the United States, Jewish summer camps have been around for about a century, spanning the religious and political spectrum. Some Jewish community leaders consider camps to be among their most successful endeavors. Indeed, for a sizeable number of American Jews, the weeks spent at camp form the foundation of their lives as Jewish adults, which endures long after their last color war or campfire songfest or Sabbath service by the lake.

Camps are sites defined by fleeting time—both the brief months of summer and the swift years of youth. This means that camps are meant to be left behind— first annually, when the school year begins; then, with the end of adolescence, camps are usually abandoned more or less permanently, except for the occasional reunion. Because camps exist within this limited period, it is strange to visit them outside of that time—off-season, in adulthood. And because camps are utopian sites of fantasy, where normal time seems suspended, it is especially provocative to encounter campsites when they are no longer places where dreams are pursued.

“Summer Joins the Past,” Albert J. Winn’s series of photographs of abandoned Jewish summer camps in North America, currently on view in the Open Lens Gallery of Philadelphia’s Gershman Y, offers a quiet yet eloquently evocative tour of these places out of time. The sixteen black-and-white images on display, originally taken in 2000 and 2001, show sites familiar to anyone who has ever been to summer camp—the swimming pool, the mess hall, the baseball field, the bunkhouse—but oddly bereft of their familiar summertime use.

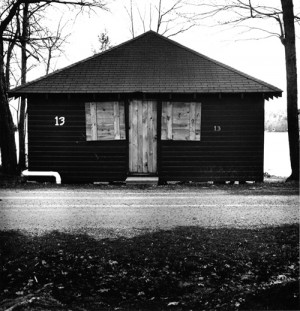

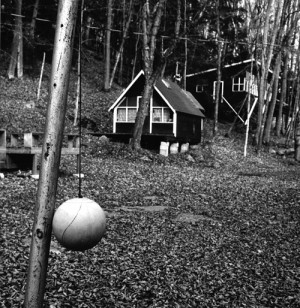

Light burnishes the windows of dark interiors to reveal a sleeping, out-of-season inventory: a stack of metal bedframes on their sides, a cluster of upside-down canoes. Some images, such as a leaf-strewn tennis court, appear familiarly pastoral, with only a hint of wistful emptiness. Others are more haunted, suggesting sudden departure: a bunkhouse bureau with empty drawers open awry or sheets still on the beds. Even more poignant are signs of long neglect—walls half-covered with overgrown brush, broken tree limbs covering the bleachers beside the ball field— leaving Nature to reclaim, slowly, the utopian landscape.

No people appear in these photographs. Instead, their absence is rendered palpable by telling details: graffiti covering every surface of bunkhouse walls, two opened envelopes (letters from home?) left lying on the floor, a tetherball hanging limply from its pole, a door with a big “X” painted on its front. Most evocative are small buildings, their windows boarded up, looking like hibernating gnomes. One, a miniature synagogue amid barren trees, bears two large Stars of David flanking a center door, their paint running down the wall like tears.

The haunting, slumbering emptiness of these images invites viewers to awaken them and, in doing so, to imagine. Not all thoughts are of the idylls of summers past. Winn reports that quite a few people find some of his summer camp photos evocative of the Holocaust: shower stalls, wooden cabins with spartan bunk beds. This association may be, he suggests, more revealing of how Americans have come to see the Holocaust. (I am reminded that a 1961 episode of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone, about an unrepentant Nazi who returns after the war to the abandoned grounds of Dachau, motivated by sadistic nostalgia, was filmed on an empty summer camp in upstate New York.)

For Winn, as a man living with AIDS since 1990, these images have a different resonance. In his notes for the exhibition, he explains that, by taking these pictures, he sought “a way to express the memory and sense of loss I was experiencing. I also wanted to create images that would both transcend the specificity of my AIDS experience and speak more generally to others, to locate that sense of loss and memory in a place that would evoke similar feelings, a place with which others could identify.”

Winn describes his summer camp photos as part of a larger effort of using a camera to explore his life’s journey. He has done this most directly in “My Life Until Now,” an ongoing series of self-portraits, some of which directly juxtapose his Jewishness with being a gay man living with AIDS (most provocatively, a photograph of his naked torso and an arm, wrapped with his tefillin, the leather straps surrounding a bandage that covers a spot in the crux of his elbow, where blood was drawn). Turning the camera on himself provides Winn with a powerful means of self- scrutiny and of confronting viewers forthrightly.

The photographs in “Summer Joins the Past” invite a more oblique engagement, as Winn looks out from the self and toward the past. These images call for close examination of what seems at first a familiar milieu, so as to discover what is different, what is missing. This includes discovering the photographer’s implicit presence, as he trespasses the boundaries of summer and of youth in search of lost innocence, youthful vitality, comradeship, and, formative ideals.

My own reactions to Winn’s photographs are not those of an ex-camper. (I never went to a Jewish summer camp, but I do owe my existence to the fact that my parents met while working as counselors at a Jewish camp in the Poconos.) Rather, as someone who studies American Jewish life of the past century, I scrutinize these images as documents of neglected cultural landmarks. Like summertime and adolescence, the utopias of Jewish summer camps can be fleeting. Some of the abandoned camps that Winn photographed for this project—in addition to camps in the Poconos, Catskills, Maine, and Ontario, which appear in the images exhibited in Philadelphia, he visited camps in California and the Adirondacks—were founded by Jewish movements that once flourished and then declined. Through these photographs, Winn takes viewers on a kind of archeological expedition not only to forgotten Jewish places but also along the dynamics of American Jewish ideals. These ideals were realized in isolated compounds carved out of the woods, places where life was envisioned as the pursuit of perfection, an eternal summer for the endlessly young.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?