Music Is the Food of the Soul

Listening to anyone who lives to be 100 is bound to inspire reverent concentration. Listening to a woman who is a brilliant pianist, Holocaust survivor and exceptionally lucid student of the human condition is an experience so intense that it’s impossible to return to the banalities of everyday life unchanged. Perhaps that’s why director Christopher Nupent’s new film Everything in the Present: The Wonder and Grace of Alice Sommer Herz is so relentlessly spare: he wants to leave us room to sort out our belongings.

Although technically a documentary, the film lacks the techniques we’ve come to associate with the genre in the age of Ken Burns and A&E’s Biography. It would have been simple to have paired Sommer Herz’s words with images of the people and places she describes or interspersed her present-day commentary with footage of the concert performances she was still giving into her nineties. Indeed, that sort of media-rich environment has become so prevalent that its absence here is viscerally apparent. It’s as if Nupen wants us to understand that this sort of testimony can only be diminished by technological enhancement.

To be sure, Sommer Herz exerts a commanding presence despite the mediation of the television or computer. Watching the film, I repeatedly had the same deep thrill that would flood me when my grandparents would tell me about their lives, that shiver that arcs through the spine in the moments when we feel most alive. Despite the fact that many of Sommer Herz’s stories are “schrecklich” and “fürchtbar” – she usually switches from English to German when describing her years of persecution by the Nazis – I experienced this sensation as pleasure. She testifies too powerfully to the limitless potential of the human spirit to come away from the film frightened or depressed.

In a film that resolutely avoids tricks of the documentary trade, Nupen only breaks with the “talking head” format for short interludes that show a close-up of Sommer Herz’s hands while she plays piano. This formal choice aligns perfectly with the content of her testimony. She explains that music literally provided her the sustenance she needed to stay alive when she didn’t have enough to eat. At the “model” concentration camp in Terezin where she was interned, she adds, it was the musicians who managed to stay healthiest. “Wenn wir gespielt haben,” Sommer Herz declares, “war es wie ein Gottesdienst”: playing in the camps was like a religious service. In the hell of the KZ, music provided a glimpse of paradise. That’s why she states, “Nature and music: this is my religion.”

Coupled with her passionate defense of German culture, including Richard Wagner, this assertion marks Sommer Herz as someone who stubbornly adheres to the values of the highly educated Middle-European Jews who strived for assimilation even when it was against their own self-interest. Describing the tense days prior to her deportation to Theresienstadt, she tells the story of the Nazi officer who lived in her building who let it be known that he greatly enjoyed hearing her piano playing through the floor. On the day when she was finally forced to leave, her Czech neighbors came to rummage through her possessions without regard for her family’s feelings. But the Nazi officer stopped by to offer a polite farewell, fervently stating his wish that she survive the war in good health.

Those who have no patience for such tales of the “good German” may have a harder time with Sommer Herz’s testimony than other viewers. Although she emigrated to Israel after the war, performing and teaching for decades, it’s clear that her heart never left pre-war Prague, a place where it was possible to believe in the virtues of a proto-multiculturalism. She makes it clear that Czech, German and Jewish culture were in competition with each other, but still seems to believe that they should be appreciated together.

Then again, when a person experienced that world as she did growing up – tagging along to the weekly meetings of Franz Kafka’s writing group, being friendly with Gustav Mahler’s family, having Sigmund Freud visit her house – her impulse to redeem the promise of late Habsburg Prague is easy to understand. And, as the film makes clear, it is not the product of delusion. She acknowledges the limits of that society, its failure to protect many of its most talented inhabitants. But she finds it more productive to acknowledge the capacity for good and evil in all human beings than to stereotype them on the basis of their heritage.

This attitude, also reflected in Nupen’s 2004 film We Want the Light, about the fraught musical relationship between Jews and Germans, is what makes Sommer Herz such a profound inspiration. “To be thankful,” she concludes, is the chief lesson she has learned in her long life. “Everything is a present. This I learned, to be thankful for everything.” For those who spend their lives filled with resentment and fear despite never having to go through what she did, this insight serves as a powerful rebuke, but one whose sting is softened by the depth of her magnanimity and the brilliance of playing.

It’s interesting, in this light, that no mention is made of one of the key aspects of her musicianship. Because sheet music was so difficult to come by, she learned to play her favorite pieces from memory. The concerts she gave in Theresienstadt, which she often repeated on request, burned the notes into her brain to such a degree that the music became, in essence, a part of her body. Watching her aged hands move up and down the keys, this quality is something we are made to feel without words.

Others have played the music featured in the film better from a technical standpoint. Sommer Herz surely did herself, in her younger days. But it’s hard to imagine the soul of the music being more effectively communicated than it is in the excerpts filmed for Everything Is a Present. Her conviction that music is the highest expression of human capability and, what is more, the way to stay alive resonates through every note.

Maybe this is why Nupen chose to isolate her hands, allowing us to focus on what matters most to her. For me, though, the decision paid more specific dividends. My maternal grandmother, born three years after Sommer Herz, was a talented concert pianist – she once defeated future composer Samuel Barber in a competition – who was unable to pursue a musical career because her family refused to support what they deemed to be an unladylike career.

Although she went on to become a teacher, her affair with the piano was only requited in the claustrophobic privacy of her own home. It was one of the things that made her bitter, a woman smarter than her circumstances, acerbic to a fault. Yet when she sat down at her baby grand and started to play her favorite Chopin pieces from memory, the burden of her personal history temporarily melted away.

I used to watch her wrinkled fingers when I was small and marvel at the change in her, one that I measured by the permission she always gave me afterwards to peck away at the keys myself, her possessiveness towards the piano temporarily muted. Watching Sommer Herz’s hands in Everything Is a Present, I periodically found myself transported back in time to those times when my grandmother stopped being the tense woman I was rather wary of and turned into a giant.

When Nupen decided to film all of his piano shots in close-up, he may have merely wished to highlight the remarkable passion and proficiency that Sommer Herz still displayed at age 98, when the sequences were filmed. But he ended up facilitating an identification with the film that goes beyond its historical content. Or, to put that another way, he made it possible for viewers like myself to feel their own personal history in the telling of hers.

While that aspect of the film may seem to distract from its main purpose – this is the testimony of a Holocaust survivor, after all – I think that Sommer Herz would approve. Over and over again, she indicates that music saved her in Theresienstadt because it had the capacity to free her temporarily from the indescribably terrible reality of her day-to-day existence. The transcendence it offers, though, isn’t just available under such appalling conditions. Whenever we let ourselves be fully absorbed in the music, as she obviously is when playing the excerpts featured in the film, we are partaking, in effect, in a “Gottesdienst.”

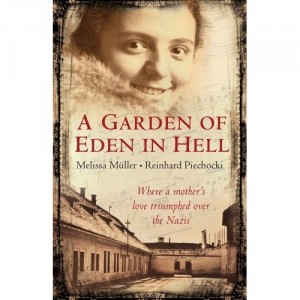

Those who are fascinated by Sommer Herz’s story will want to watch We Want the Light and read the book A Garden of Eden in Hell, which appeared in English translation in 2008. But the directness and simplicity of Everything Is a Present is a wonder not to be missed. This is a case where less is truly more. Whether as a complement to other Holocaust testimony, an oral history of a storied time and place or as a testament to the resources of the human spirit, Nupen’s film belongs in every public library and plenty of private ones as well.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?