Jewish Enlightenment : Neo-Hasidism and Vedanta Hinduism

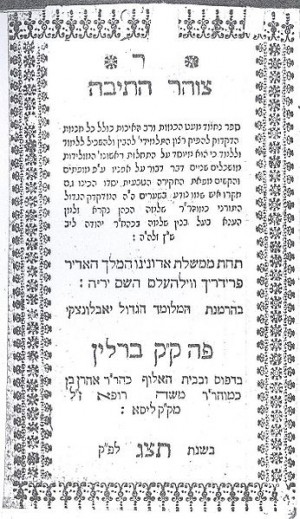

“Enlightenment” is sometimes regarded as a purely “Eastern” concept, foreign to the Western monotheistic religions and to non-Western indigenous and shamanic traditions. But this is not the case. In fact, the most important book of Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical and esoteric tradition, takes its name (Zohar) from the prophet Daniel’s (Daniel 12:3) prediction that “the enlightened (maskilim) will shine like the radiance (zohar) of the sky.”

Here, I will explore some of the distinctive features of what we might call “Jewish enlightenment” as expressed in Kabbalistic and Hasidic sources, and draw some comparisons with enlightenment as conveyed in other traditions, particularly Advaita Vedanta, the nondualistic strand of Hinduism that gave birth to much of the “New Age.” My comparison, though attenuated in form, will be both theoretical and historical, for as we shall see, Vedanta greatly influenced 20th and 21st century neo-Hasidism in its conception of and approach to ultimate truth.

1.Jewish Enlightenment

The Zohar explains that the enlightened are those who ponder the deepest “secret of wisdom.” (Zohar 2:2a) What is that secret? The answer varies from text to text, tradition to tradition, but in the Zohar and elsewhere, the deepest secret is that, despite appearances, all things, and all of us, are like ripples on a single pond, motes of a single sunbeam, the letters of a single word. The true reality of our existence is One, Ein Sof, infinite, and thus the sense of separate self that we all have — the notion that “you” and “I” are individuals with souls separate from the rest of the universe — is not ultimately true. The self is a phenomenon, an illusion, a mirage. For a moment, such forms appear, like letters of the alphabet, momentarily arrayed into words — and then a moment later they are gone. In relative terms, things are exactly as they seem. But ultimately, everything is one — or, in the theistic language of the Kabbalists, everything is God.

One common Kabbalistic formulation of this principle is that God “fills and surrounds all worlds”—memaleh kol almin u’sovev kol almin. This formulation is found in the Zohar (for example, in Zohar III:225a, Raya Mehemna, Parshat Pinchas) and other medieval texts, such as the twelfth century “Hymn of Glory” which says that God “surrounds all, and fills all, and is the life of all; You are in All.” The aspect of memaleh, filling, is sometimes described in fully panentheistic terms, and other times in terms of God as a sort of life force, or organizing principle.

For example, (Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla)[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_ben_Abraham_Gikatilla], among the most prominent members of the circle of medieval mystics thought by scholars to have composed (or redacted) the Zohar, is recorded as saying “he fills everything and He is everything.” Moshe de Leon wrote that his essence is “above and below, in heaven and on earth, and there is no existence beside him.” Yet the Zohar itself sometimes takes a less fully panentheistic position, as in the passage cited above: “He fills all worlds … He binds and unites one kind to another, upper with lower, and the four elements do not cohere except through the Holy Blessed One, as he is within them.” (Zohar III:225a).

Another important Zoharic formulation of nonduality is the statement that leit atar panui mineha, “there is no place devoid of God.” This phrase is found in the Tikkunei Zohar (57), a later addition to the Zoharic literature, but accorded great respect by subsequent generations of mystics. On a simple level, this sentence conveys the doctrine of omnipresence, and it was taken literally by Chabad Hasidism: “The meaning of ‘He fills all the worlds and there is no place devoid of Him’ is truly literal,” says one text.33

Eventually, panentheism becomes a well-developed theological position among key Kabbalists and Hasidim. In the sixteenth century, Moses Cordovero, probably the greatest systematizer of Kabbalah, wrote that:

The essence of God is in every thing, and nothing exists outside of God. Because God causes everything to be, it is impossible that any created thing exists except through Him. God is the existence, the life, and the reality of every existing thing. The central point is that you should never make a division within God … If you say to yourself, “The Ein Sof expands until a certain point, and from there on is outside of It,” God forbid, you are making a division. Rather you must say that God is found in every existing thing. One cannot say, “This is a rock and not God,” God forbid. Rather, all existence is God, and the rock is a thing filled with God … God is found in everything, and there is nothing besides God. (Perek Helek, Modena ms. 206b, translation mine)

and:

God is all reality, but not all reality is God … He is found in all things, and all things are found in Him, and there is nothing devoid of God’s divinity, God forbid. Everything is in God, and God is in everything and beyond everything, and there is nothing else beside God. (Elimah Rabbati 24d-25a, translation mine)

The most clearly nondualistic statements in traditional Judaism, though, appear in the 18th and 19th centuries with the advent of Hasidism. “Nothing exists in this world except the absolute Unity which is God,” the Baal Shem Tov is reported to have said (Sefer Baal Shem Tov, translated by Aryeh Kaplan in “The Light Beyond”)[http://www.amazon.com/Light-Beyond-Adventures-Hassidic-Thought/dp/0940118335]. His disciple, the Maggid of Mezrich, wrote that “God is called the Ein Sof. This means that there is nothing physical that hinders God’s presence. God fills every place in all worlds, both spiritual and physical, and there is no place empty of God.” (Torat HaMagid, trans Aryeh Kaplan) A later Hasidic master, R. Aharon of Staroselse, wrote that “Just as God was in Godself before the creation of the worlds, so the Blessed One is alone [l’vado] after the creation of the worlds, and all the worlds do not add to God (may he be blessed) anything that would divide God’s essence (God forbid), and God does not change and does not multiply in them, and the worlds (God forbid) do not add anything additional to God.” (Shaarei haYichud v’HaEmunah, 2b) In the Yiddish of one lesser-known Hasid, R. Yitzhak of Homel, “Es is mehr nito vie Ehr alein un vider kehren altz is Gott .” That is: There is nothing but God alone and, once again, all is God.

2.Ways of Speaking Silence

Such statements may be quite familiar to followers of other mystical traditions, and students of the “perennial philosophy.” Yet there are some distinct features of the Jewish conception of enlightenment, both in content and presentation, that distinguish it from others.

First, whereas some traditions regard the knowledge of nonduality as the ultimate wisdom – the last stop on the road, so to speak; the final teaching – in the Jewish mystical tradition, nonduality is the beginning rather than the end of wisdom. Jewish mystics begin with the shocking, and proceed to the ordinary. The Zohar, for example, spends much less time describing Ein Sof than it does with the details of the sefirot (emanations), not to mention angels, demons, and the mythical stories of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his circle. Likewise Cordovero, who devotes many pages to parsing the details of emanation and cosmology. Ein Sof is the basis, rather than the conclusion, of Jewish mystical theosophy.

Second, Jewish texts often conceal nondual philosophy within layers of symbol, language, or outright obfuscation. Vedanta texts, for example, have a clarity and forthrightness absent in the Jewish ones. Indeed, when, in the 19th century, Hasidic books were burned by their opponents, one of the stated reasons was that they made plain that which should be kept secret. Why do Advaita sages speak so directly, while Jewish ones seem to talk in riddles? One answer may be that nondual Judaism evolved over time, and was at first a secret, marginal tradition, whereas in Hinduism, nonduality is present right from the beginning and was the subject of enormous philosophical speculation. Moreover, Judaism’s rigorous monotheism invites a certain reticence when it comes both to theological polymorphism/polytheism and to monism, whereas Hinduism is at home with both.

Or perhaps the occasional reticence of the Jewish mystics is due to their clear understanding of the potential dangers of radical nonduality. If there are no distinctions in the absolute (e.g., forbidden and permitted, self and other, light and darkness, body and mind), then the religion of the relative, with its rules and prohibitions, suddenly becomes incoherent. If nothing else, Judaism is a religion of distinctions and lines, and if Ein Sof erases lines, it erases normative Judaism. Nor does Judaism possess a serious monastic tradition; even mystics were expected to be householders.

These cultural features of Judaism also colored the experience of enlightenment itself. Hasidim, in particular, understood the enlightened consciousness not as a “steady state” but what they called ratso v’shov, literally “running and returning.” This phrase, from Ezekiel 1:14, has come to stand for any number of oscillations in spiritual life—for example, between expanded and contracted mind, being and nothingness. And it was understood that a mystic would have to experience such oscillation, as he (always he) contemplated the highest unity at some times, tended to the needs of his family and community at others. Often, the tzaddik, the leader of the Hasidic community, was expected both to enter the highest states of what we might call God-consciousness, and to provide for the community’s material and spiritual needs. For this reason, the experience of enlightenment is one of oscillation between what one Hasidic master called “God’s point of view” and “our point of view.”

Now, in some Hasidic conceptions of this view, one finds the opinion that, indeed, both points of view are of the same reality—they are just different points of view. “Ours” sees objects, people, and things. God’s sees only Godself. The object is to see both as two sides of the same coin. Neti-neti, the Vedantists say: not-this, not-that. Neither twoness nor oneness, neither yesh nor ayin, but both, and thus neither. Enlightenment, after all, is not merely a sense of oneness. That “all is one” is exactly half of the picture.

Does this position lead to the experience of everyday life, even “unenlightened” life, as the experience of God? Some Hasidic texts lend themselves to such an interpretation – the stories of a Hasid wanting to know how his rebbe tied his shoelaces, for example, or Martin Buber’s formulation of Hasidism as a “mysticism of ordinary life.” Yet Judaism, and by extension Kabbalah and Hasidism, is neither systematic nor univocal. Some texts do seem to suggest that everyday experience can be suffused with devekut, or cleaving to God. Others suggest that the state, like samadhi, arises only under special conditions.

What we can say, though, is that within normative Judaism, there are almost no statements that the manifest world is illusion, or devoid of importance. This is a final distinction between Jewish enlightenment and the ultimate truth as conceived in some other traditions: that in the Jewish model, even though everything is God, the manifest world still maintains some reality of its own. Responding both to general Jewish norms of ethical and ritual commandments (mitzvot) and to specific historical trends in the 18th century (mystical heresy), Hasidic texts insist that the apparent world does exist in some way (even if only as a matter of perspectives), and that our actions within it still have significance. They almost never advocated antinomianism, quietism, or abrogation of ethical norms. Within a tradition whose centerpiece is a Torah of this-worldly commandments, it could hardly be otherwise.

3.Neo-Hasidism encounters neo-Vedanta, or, West Imagines East

In the 20th century, West did, finally, meet East. As told by critics of New Age Judaism, the usual story is of a Jewish spiritual seeker being entranced by “Eastern” ashrams and meditation, and then creating “Jewish” versions of these other traditions. In fact, however, the historical narratives of contemporary neo-Hasidic nondual Jewish leaders are quite different. Some, indeed, are seekers, finders, and returners. Others, such as Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, were traditionalists concerned about Jews leaving traditional Jewish practice who promoted Jewish alternatives to Zen, Vedanta, and 1960s spirituality. And some, like Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi and Rabbi Arthur Green, were knowledgeable “insiders” taking inspiration from how other traditions presented spiritual, experiential aspects of their religions. “I was very excited,” Reb Zalman told me, “to find out how they were dealing with spirituality and the questions that Ramakrishna raised about how to deal with monism and dualism, and everything that he had to say really made a lot of sense to me.” Green reported that

I marveled at the way the Indian teachers coming to the West seemed to be ready to shed so much of their particularity. I remember meeting Satchitananda and realizing that he was not interested in making people Hindus or teaching them Sanskrit. He said, “Close your eyes and chant om shantih om with me, that’s all you have to do—be present in the moment.” But [in the Jewish community,] it was, “Keep shabbos and kashrus and fifteen years later we’ll talk to you about mysticism.” The Jewish way in was an arduous way in.

Implicit in Green’s account is, of course, a privileging of the immediate spiritual experience over communal affiliation, ritual observance, and, one might add, belief. While Green casts this particular episode in terms of particularity and universality, these additional assumptions play an equally important role, insofar as they condition the validity of the “that’s all you have to do” statement of the yogi – a statement which itself is likely more an invitation than a description of the mystical path. Moreover, these assumptions – we might more favorably call them foundational principles – animate a great deal of the neo-Hasidic preference for the immediately available, experiential forms of ‘mysticism’ over the more complex, textual, and tied-to-observance forms prevalent in the Kabbalah. That is to say, by importing from Hinduism (in this case) an ostensibly methodological/ pedagogical procedure – making spirituality available – neo-Hasidism actually supplanted the Kabbalah’s substantive orientation toward more textual and less immediately experiential forms. Even ecstatic Hasidic prayer, after all, is usually tied to some form of textual prayer liturgy. The tacit functionalism of “this provides an experience – how can we do that” is thus a non-transparent preference for a certain kind of experience, as well as a pedagogical assent that such an experience should be made available to everybody. In this regard, there is a clear distinction between Vedanta, as it came to be transmitted in the West, and Kabbalah/Hasidism.

Indeed, Satchitananda’s method was no accident. Contemporary Vedanta, one of the primary sources of 1960s and New Age spirituality, was itself a “renewed” tradition. Vivekananda presented Vedanta for Western audiences, stripped of Hindu particularism, ritual requirements, and technical language, and deliberately positioned as a kind of post-religion religion. Christopher Isherwood, Aldous Huxley, and others translated Vedanta texts and teachings, adapting them for Western ears and concerns. In fact, by the time Vedanta encountered the 1960s, we may speak of a “neo-Vedanta” as much as a neo-Hasidism. Neo-Vedanta presented a popular, accessible form of mysticism, which emphasized the nondual core of Vedanta teaching, which resonated with both contemplative and entheogenic experiences of the time.3 Reb Zalman called it “Vedanta for export.”

Nondual neo-Hasidism adapted this model. Where Kabbalah was obscure and text-centered, neo-Hasidism became experience-centered—like neo-Vedanta. Where Kabbalah insisted both on outward performance and inward intention (shell and kernel), neo-Hasidism emphasized the latter over the former—like neo-Vedanta. Where Kabbalah (and even Hasidism, for most of its history) was elitist, neo-Hasidism was populist—like neo-Vedanta. And where Kabbalah was particularist and even ethnocentric, neo-Hasidism was universalistic and ecumenical—like neo-Vedanta (“they filtered out all the ethnic stuff,” Reb Zalman told me). Thus we may say that in the case of pedagogy, neo-Hasidism clearly adopts the Vedanta Society’s openness, unambiguously preferring it to the traditional Jewish reticence. I have suggested that in so doing, it also perhaps unconsciously adopted some of Vedanta’s philosophical priorities, emphasizing inwardness and spiritual experience over particularism, study, and ritual action to an extent not found even in Jewish mystical sources. And neo-Hasidism embraced Vedanta’s universalism, even while it recognized – and indeed, perhaps encouraged by – its somewhat constructed nature.

The embrace was not total, however. In fact, Neo-Hasidism often sought to distinguish itself from Vedanta – going so far as to imagine distinctions where there were none. For example, many contemporary Jewish spiritual writers regard engagement with the this-worldly as a kind of litmus test of right spirituality, often projecting a quietistic, monastic “Hinduism” to serve as a kind of foil; Judaism, it is said, is this-worldly, rather than other-worldly. This despite Vivekananda’s intense social and political activism on a global scale. Many contemporary Jewish writers see Judaism as “hot,” theistic, and devotional, in contrast with a “cool,” nontheistic, and contemplative Vedanta – notwithstanding Ramakrishna’s insistence on devotion and countless Vedantic devotional practices. And neo-Hasidism rarely fully embraces acosmism, again ascribing it to an imagined Hinduism, notwithstanding Ramakrishna’s similarly “both-and” theological stance:

Brahman is neither “this” nor “that”; It is neither the universe nor its living beings … What Brahman is cannot be described … This is the opinion of the jnanis, the followers of Vedanta philosophy. But the bhaktas [devotees] … don’t think the world to be illusory, like a dream. They say that the universe is a manifestation of God’s power and glory. God has created all these—sky, stars, moon, sun, mountains, ocean, men animals. They constitute His glory. He is within us, in our hearts … The devotee of God wants to eat sugar, not to become sugar.

Things are not, then, what they seem. Neo-Hasidism is not the tale of the “wandering Jew” who wanders far afield before discovering the riches in his backyard. In fact, most neo-Hasidic leaders were versed in Judaism and Kabbalah first, and came in contact with Vedanta and Buddhism, in their Western forms, later. Nor is Vedanta the cool, other-worldly monism imagined by its critics. That said, the distinctions are not entirely imaginary. There are surely more tales of equanimity and quietism within Vedanta, as within most Buddhist schools, than Hasidisim. Quietism is considered a “problem” within Hasidism, and the seclusion of R. Menachem Mendel of Kotsk a vexing dilemma for neo-Hasidim, particularly Abraham Joshua Heschel. The quietism of Ramana Maharshi, on the other hand, is not a “problem” at all for his devotees. And while Hasidism made much use of the term hishtavut, equanimity, both its tales and its theological literature are more replete with narratives of struggle and delight than with records of transcendence and equanimity; the tzaddik is generally depicted as one who cares, cries, prays and provides for his community. He is an intercessor with the Divine, an active leader – not a sage or a saint in the Ramana mode. To reiterate, the distinctions here are less clear than neo-Hasidic rhetoric would suggest – that is my primary point. But they do have some basis at least in the divergent emphases placed by the traditions on the cognitive and emotive nature of enlightenment.

No doubt, as with all syncretic movements, neo-Hasidism was possessed of a certain anxiety of influence, at pains to insist that its teachings were indigenous, even though they may owe at least as much to other religious traditions. Yet, and with this I conclude, neo-Hasidism is a quintessentially American, postmodern religious movement, led in part by part-time academics who themselves, like this writer, function as it were both as primary and secondary sources, as generators of religious thinking and as self-reflective, academically trained critics of it. Neo-Hasidism is peculiarly aware of this integral move, which joins not just disparate religious traditions as in traditional syncretism but even religious traditions with academic ones, spiritual consciousness with self-consciousness. Perhaps it is this peculiar disposition that neo-Hasidism has the most in common with Vivekananda’s self-conscious re/presentation of Vedanta, and even with the nondual vision itself. The mystics already know the dividing lines, and already seek to transgress them.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Jay Michaelson

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats