Kicking Away the Ladder: Immigrants, BIDs & an Uncertain Future for Street Peddling in NYC

Will a Business Improvement District in Queens deprive new immigrants of the opportunities that helped so many 19th- and early 20th-century Jewish families secure a successful footing for their families in the United States?

Roosevelt Avenue Community Alliance

A speaker at the February 1st Town Hall meeting about the future of Roosevelt Avenue in Queens.

Like a lot of Jewish kids, I grew up hearing about the ways my family first experienced life in America. In 1902, my great-grandparents Solomon and Sarah Stein journeyed from Poland to Ellis Island, and the following year they had their first child. The family started out on Allen Street — now renamed “Avenue of the Immigrants” — until they crossed the Williamsburg Bridge, rented a place in Bushwick, and eventually settled in Midwood. With limited English and education, Solomon and Sarah did what they could to provide for their kids. Sarah sewed clothing at home; they couldn’t afford a storefront, so Solomon would sell the clothes in the street, going door to door building a customer base. They raised a family of five children, all of whom went to college.

That’s one of my family’s foundational stories, and it’s one that binds us to many other Jewish Americans. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, peddling and street vending were crucial economic development tools for Jewish immigrants to New York City. The street economy was a way for newcomers with little savings or access to credit to start a business, make a living, and eventually build some wealth. Many of the famous Jewish department stores actually grew out of street carts and mobile businesses run by recent immigrants.

Today, street vending is still an important way for new New Yorkers to make a living, and an iconic part of city life. In many ways, the only thing that has changed is where people are migrating from, and where in the city they live and work. Whereas most 19th and early 20th-century immigrants were European — a fact ensured by racist immigration laws that disallowed just about everyone else — today’s immigrants to New York are 32% Latin American, 27% Asian, 19% Caribbean-nonhispanic, and 4% African. Of these, more than 35% have found their way to Queens.

One result of these shifts is a plethora of immigrant businesses along Queens’ major commercial drags, including a great many popular street vendors. Nowhere is this dynamic more visible and vital than Roosevelt Avenue, one of the liveliest streets in all of New York City. Beneath the 7 train’s rumble, small businesses — from bodegas and bakeries to queer clubs and dive bars — line the street, with tiny professional offices and studios above. Just about every block features several street vendors, selling arepas and choclo, freshly fried empanadas, Oaxacan tamales, cut fruit, books in several languages, shoes, T-shirts, toys and more.

Rafael Samanez, proprietor of the Morocho Peruvian Fusion cart and executive director of the vendors’ rights group Vamos Unidos, points out that the rise of Roosevelt Avenue as a vendors’ haven corresponds closely to changing patterns of immigration into the US.

“As newer folks migrated to the US, as 1994 hit and a lot of migration started increasing from Mexico, you saw a lot of these trucks selling Mexican food opening up. There’s Dominican food, migrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and they started opening up their carts.”

For new immigrants, as for my great-grandparents a century ago, street vending in New York is intimately linked to the city’s status as a magnet for migrants. It has always been hard work, and conditions (especially in winter) are far from ideal, but peddling in places like Roosevelt Avenue is a way of life and a path out of poverty. That path, however, may soon be blocked.

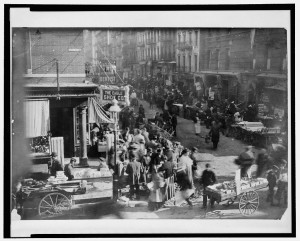

Sunday morning at Orchard and Rivington, NY (circa 1915), George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress

Street vendors in early 20th-century New York, Manhattan’s Orchard Street.

There is a movement afoot to frame Roosevelt Avenue as “blighted” and “dangerous” and sweep away the immigrant workers that make the place run. Queens City Council Member Julissa Ferreras — a Democrat and Working Families Party member, no less — has said that Roosevelt Avenue looks like “a poor sector of the Third World” and claimed that “the greatest problem is between 69th and 111th, which is the Latino part.”

Under the guise of public safety, Council Member Ferreras and other elected officials are pushing for the formation of the largest Business Improvement District (BID) in the city, which would stretch along Roosevelt Avenue from 81st Street to 104th Street. If they are successful, this would spell a great deal of trouble for today’s immigrant street vendors and peddlers.

Many Queens community groups support city action to improve Roosevelt Avenue. Jackson Heights’ New Immigrant Community Empowerment, for example, has been drawing attention to businesses on Roosevelt Avenue that run scams that prey primarily on new immigrants with false promises of jobs and affordable homes. They are calling for an investigation into these corrupt practices. Make the Road New York, an immigrant and workers’ rights organization, has decried the NYPD’s practice of arresting LGBTQ people for prostitution, simply because they are walking on Roosevelt Avenue with condoms in their pockets. They are calling for an end to these bigoted and backward policies.

These are serious problems that the city needs to address; unfortunately, the push for a Roosevelt Avenue BID has more to do with raising property values and evicting vendors than stopping systemic abuses.

BIDs are a way of securing private management of public space. In such districts, landlords collect fees from their tenants, and use the money to provide private security and sanitation services. They lobby — often successfully — for specialized legislation to “improve” the business climate in their neighborhood. Usually that means driving away street vendors, shooing away those they don’t believe belong, discouraging diversity in signage and design, and generally disciplining street culture.

As an organization run entirely by landlords, without meaningful input from residents, businesses or vendors, New York’s BIDs are a model of oligarchic city governance. In her book Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places, sociologist Sharon Zukin — a professor at Brooklyn College and at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York— argues that BIDs “embody the norm that the rich can rule.” She writes:

First, because big corporations and landlords have more money than the public sector, they have been granted the responsibility of planning and paying for basic services. Second, because voting rights within each BID reflect the total taxable value of each member’s land, owners of the most valuable properties have the most power.

This is a key to understanding why neoliberal New York has been so hell bent on building BIDs/. Ultimately, BIDs are a way for the wealthy to reassert control over urban space in areas where the working class has informally carved out a niche for itself.

The first BID was formed during the second Koch administration. The BID system really took off, however, under Rudolph Giuliani, a mayor known for his aggressive attack on street vendors. Under his watch, BIDs managed to close off more than 300 streets to peddlers, mostly in the city’s central business districts. Under the Bloomberg administration, BIDs proliferated all over the city. While Bloomberg was less vehemently anti-vendor than Giuliani, the BIDs he promoted extended the attack on peddlers from Manhattan to the boroughs. Under Bloomberg’s watch, the number of BIDs in the city swelled to 68, with two thirds located outside Manhattan.

As BIDs spread throughout the city, vendors began to notice an uptick in police crackdowns that exploit ambiguities in the laws concerning street vending. For example, many carts have been closed by police officers who demand not only that the business have a permit, but that the permit holder be present at all times. It is not at all clear that this is the letter or intent of the law, but it is a common practice in neighborhoods with BIDs. Once these crackdowns begin, they tend to escalate. Some 40% of street vendors report having police confiscate their goods, according to a recent survey by the Urban Justice Center’s Street Vendor Project. Only about half were able to have their goods returned. Many have been harassed by the police, and spend precious workdays fighting specious tickets.

In Jackson Heights and Corona, street vendors and small businesses are organizing against the proposed BID, and have formed the –Roosevelt Avenue Community Alliance, RACA, as a vehicle for their movement. Bringing together street vendors, small business owners, tenants and community groups — including Vamos Unidos as well as the South Asian youth and workers’ center DRUM-Desis Rising Up and Moving— they are working to educate the community about the dangers a BID poses to immigrant families, and the neighborhood as a whole.

According to Marty Kirchner, a founding member of RACA, the group’s top priority is a “vote no” campaign — an effort to position the BID’s main stakeholders against the privatization and homogenization of Roosevelt Avenue. “Another key priority,” Kirchner told me, “is to put political pressure on Councilmember Julissa Ferreras to convince her that her constituencies (including neighborhood residents who won’t get a vote in the BID process) are vocally opposed to the BID, and that Ferreras should become active in effectively preventing the BID from forming.”

Right now, the BID is trying to raise support for its upcoming vote, which they project will be held this spring. That vote, however, is only advisory; the power over BID formation is held by the local City Council member, the city’s Department of Small Business Services, and the City Planning Commission. According to RACA’s Marty Kirchner, however, the BID “told us if a large portion of people vote against it, they’ll take that as a signal that the community isn’t behind it.”

Rafael Samanez of Vamos Unidos believes strongly that the Roosevelt Avenue BID can be stopped. “Since the beginning of BIDs, they’ve always had issues with the street vendors. It’s been a challenge dealing with them because they are very powerful. The difference today is that there is a very large network of different individuals and organizations fighting the Queens BID, which gives us a lot of hope.” Their meetings have been gaining traction, and more than 100 community residents attended a February 1st Town Hall Meeting. They hope this signals a changing tide in political momentum against the BID.

Roosevelt Avenue will likely be the first Business Improvement District to come up for a vote under the new City Council — led by Progressive Caucus member Melissa Mark-Viverito — and a mayor who ran on the issue of economic inequality. It will be an opportunity to hold our government accountable, and take a stand against the privatization of our city streets and the related rise in vendor harassment.

As this debate continues, it is important to keep the issue in a historical context: street peddling was an important pathway for Jewish immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries. Will we allow the city to kick away the ladder for today’s immigrant workers?

Samuel Stein is an independent writer, researcher, and organizer. He has worked in New York’s labor and tenant movements, and holds a master’s degree in Urban Planning from Hunter College. Along with his colleagues at the New York City Planners Network, he recently edited Opportunities for a New New York, a report that aims to spark conversation about the city’s planning agenda. He has written about New York City politics for such publications as Progressive Planning, Gotham Gazette, and Urban Omnibus, and is currently co-authoring a book about gentrification in Manhattan’s Chinatown with Hunter College professor Peter Kwong.

To learn more, visit the Roosevelt Avenue Community Alliance online, or follow the campaign on Facebook or on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The sentence about the BID system was updated on February 5th to incorporate the earliest BIDs in New York.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Samuel Stein

More articles in