Past & Present, Art & Activism: The Silence=Death Poster

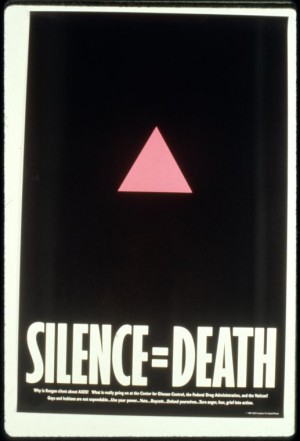

Silence=Death Project, Silence=Death (Poster). Image courtesy of the NYPL, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building /Manuscripts and Archives Division

As a founding member of the political collective that produced the image most closely associated with AIDS activism, Silence=Death, I’m frequently asked to speak about this poster. Over the decades people have thanked me for it, telling me the poster was the rallying cry that drew them to political activism.

I have a slightly different take on that. In essence and intention, the political poster is a public thing. It comes to life in the public sphere, and is academic outside of it. Individuals design it, or agencies or governments, but it belongs to those who respond to its call.

So while I had a hand in producing Silence=Death, I would argue that it was the AIDS activist community that actually created it, a community in search of its voice, one that went on to find it through the activation of its own social spaces. This image, as we currently understand it, is a product of collective world-making, the sort of collectivity which moves every one of us, as individuals and as a culture, and which is transformative.

And this is the gesture behind every work in Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism, an exhibition that travels freely between the personal and the political, and explores the tension between the stories we presume to be private and what happens when we finally say them out loud.

I’m a red diaper baby. The Rosenbergs came to the utopian colony where we summered, my folks met at an International Workers Order summer camp, my brother gave me Mao’s Red Book when I was in middle school, and my grandmother came to antiwar marches with me. When I was 16, I worked for the Poor People’s Campaign. When I was 17, I canvassed for the Student Mobilization Committee. My first job was silk screening strike T-shirts.

Regardless, to be young in the late 1960s was to be political anyway. And growing up in New York, the East and West Villages were papered with manifestos, meetings announcements and demonstration flyers. When young people needed to communicate with each other, we used the streets.

In 1981, my soul mate started showing signs of immunosuppression, before AIDS even had its name. By 1984, he was dead, a year before Rock Hudson had been outed by the disease and died, and Reagan had uttered the word. This private devastation compelled me to form a collective with two of my friends.

We started a men’s consciousness raising group that met every week, loosely assembled around feminist organizing principles. We began each session by talking about our personal fears in the age of AIDS, but by the end of every meeting we were talking about the political crisis that was forming. I knew we couldn’t be the only ones who saw it.

And then I remembered: when New Yorkers need to talk to one another, there is always the street.

So I proposed we do a poster.

The primary objective of Silence=Death was two-fold: to prompt the LGBTQ community to organize politically around AIDS, and to imply to anyone outside the community that we already were. In order to speak simultaneously to multiple audiences, the poster would need to be densely coded.

And in order to “sell” activism in an apolitical moment, the poster needed to be cool, and to intone “knowing.” It needed to be both rarified and vernacular at the same time. It needed to give the impression of ubiquity, and to create its own literacy. It needed to insinuate itself into being.

It needed to be advertising.

So the poster was strategically wheat pasted alongside commercial posters by professionals. We chose this context to signal an “authorized voice,” and to hint at resources and a level of political organizing which were non-existent. The font was graphically on trend. The black background carved its own space in the urban clutter of commercial advertising.

The poster was designed to capture its audience at two distinct entry points. For audiences from the outer boroughs who might experience Manhattan from a car or a bus, the tag line was declarative, provocative, and meant to stimulate inquiry.

For members of Manhattan’s LGBTQ communities, there were two running lines of modifying text only discernable on intimate encounter, staged in the interrogative to force the audience into dialogue with the content. The text asked the viewer to question the political, social and economic subtexts surrounding drug research and epidemiology, and the influence of religion over public policy. It then pushed for an activist response, ending with the phrase, “Turn anger, fear, grief into action.”

We realized any single photographic image would be exclusionary in terms of race, gender and class and opted instead to activate the LGBTQ audience through queer iconography. So we reviewed the symbols already in use. We felt the rainbow flag lacked gravitas. The Labrys might not be discernable to gay men. The Lambda had class connotations.

And while we initially rejected the pink triangle because of its links to the Nazi concentration camps, we eventually returned to it for the same reason, inverting the triangle as a gesture of a disavowal of victimhood.

It took us 6 months to finalize Silence=Death. We argued about issues, images and fonts. We pored over press clippings and source material. We studied the work of other collectives, like the Guerrilla Girls, who managed to compact complex messages into smooth one-liners.

We put the poster to bed in December of 1986. We started wheat pasting it in February of 1987, just weeks before the formation of the AIDS activist organization, ACT UP. We hoped the poster might stimulate some kind of collective action. But we were unprepared for what was actually coming.

In a way, ACT UP was the response we had dreamed about, but more than we had hoped for. So we decided to “open” our consciousness-raising collective to include ACT UP, and surrendered its use to the group. We provided posters for the second and third demonstrations, proposed and paid for the first run of buttons, and ushered sticker and T-shirt projects through to propel the image’s ubiquity.

An image may be authored and so, at least at that point, arguably owned. But once it reaches the public sphere, if it manages to tap into the zeitgeist, it may have its “moment.” It’s the audience that drives the “moment,” not the author. For this cultural nanosecond, the public sphere is actually an exercise in collectivity. And the “moment” is an independent thing, free in its entirety, and uncontrollable.

From that moment on, Silence=Death belonged — and it always will — to those who respond to its call.

This article originally appeared on the NYPL Blog and is reposted with permission. Special thanks to Jason Baumann, Coordinator of Collection Assessment, Humanities & LGBT Collections.

Avram Finkelstein is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn. His work is in the permanent collections of MoMA, The Whitney, The Metropolitan Museum, The New Museum, The Smithsonian, The Brooklyn Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum and The New York Public Library. Finkelstein is a founding member of the collective responsible for Silence=Death and AIDSGATE, which was recently included in “Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years at The Metropolitan Museum.” He is also a founding member of the art collective Gran Fury, with whom he collaborated on public art projects for international institutions including The Whitney Museum, The Venice Biennale, ArtForum, MOCA LA, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, Creative Time, and The Public Art Fund. He has created public awareness campaigns for AmFAR, The AIDS Policy Project, The Campaign to End AIDS, ACT UP, POZ, United Against AIDS, and ACRIA. He has conducted Flash Collectives at the HIV Is Not A Crime Conference, Concordia University, The New York Public Library, The Helix Queer Performance Network, and the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at NYU.

Four Things You Can Do Right Now

• Visit site-specific Undetectable Flash Collective installations that explore the ways that HIV and AIDS are affecting four local New York City communities. Fifteen artists, writers, and advocates answered the call to participate in a series of Flash Collective workshops with Avram Finkelstein. On view through December at the Hunt’s Point, Jefferson Market, St. George, and Washington Heights branches.

• Learn more about the Flash Collective.

• Read More About “Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism.”.

• See panels from “Why We Fight” at the NYPL’s St. George Library branch in Staten Island.

• Share your ideas about art and activism – in the comments section (and everywhere)!

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?