Nearly 10 Years After Hurricane Katrina: Here's One Conversation American Jews Need to Hear, Not Change

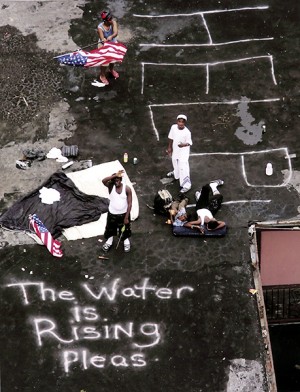

New Orleans residents sent out a desperate plea as they waited to be rescued from a rooftop. © 2005, The Dallas Morning News

It’s 2015, which means we’re almost ten years out from the cataclysm that was Hurricane Katrina. I lived in Harlem back then, stoked to finally have my own space in New York (no roommates!), even if it was a studio apartment in another family’s brownstone. I had no sunlight in my little studio, but I did have a walk-in closet.

It hardly feels possible now, but as the storm approached — even as it hit — I didn’t pay it much mind. Back in the summer of 2005, a big storm “down South” seemed like a good reason to ignore the breathless spectacle that is TV news. I consciously decided to tune out.

I remember the exact moment when I could no longer ignore Katrina. Radio reports of Louisianans stranded on rooftops and abandoned in the Superdome led every newscast, day after day. I finally gave in, wheeled my TV out of that walk-in closet, and switched it on. And, impossibly, it was all true. I saw American citizens, actual human beings, waiting on roofs for help that never came. It was sickening. In a fit of futile anger, I punched the wall of my tiny, subterranean castle. I wept.

Those actual human beings, those Americans, were — of course — African-Americans.

As a Hillel rabbi, I would ultimately lead five Alternative Spring Break trips down to New Orleans. My students willingly forfeited a week of partying to perform demolition and renovation work in and around New Orleans. On the first trip, we were given a bus-tour of the city, shown the damage that the storm had wreaked, a seemingly well-meaning white woman providing narration. After a quick overview of the damage in the Lower Ninth Ward, we headed to the tony Garden District.

The bus navigated a tight corner, revealing a stately home with the telltale ring of water damage in the middle of the first story.

“As you can see,” our guide helpfully explained, “Katrina didn’t discriminate. She hit everyone, rich or poor, black or white.”

While Katrina might not have discriminated, as a nation, the rest of us did. It was, by and large, African-American faces who paid the price of FEMA’s well-documented failures. It was African-Americans who the state of Louisiana allowed to perish when they prevented the Red Cross from delivering aid to the sick and dying in the Superdome. It was African-Americans, trying to escape that Superdome, fleeing across the Danziger Bridge, who were gunned down by the NOPD.

Katrina hit everyone. Lots of folks suffered water damage. But it was overwhelmingly black lives that were lost or forsaken. Some people, like our tour guide, wanted to talk about something else. Somehow, black lives mattered less. And somehow, it was a problem to talk about that.

I’ve been thinking of the words of our kindly tour guide as protests against police killings of unarmed black men have spread out from Ferguson and Staten Island, all across the country.

I was honored to be asked to help lead one of those protests. A group of rabbis and Jewish progressive leaders led a march through the streets of San Francisco on the first night of Chanukah. We punctuated the march with a traffic-blocking recitation of Kaddish for dozens of unarmed African-American killed by law enforcement or vigilante justice.

Following the instructions of the national black organizers, we focused solely on raising up the value of black lives. Our only demands were those outlined by the national organizers.

I expected the outcry from right wing critics. Why didn’t we focus on Jewish suffering? European anti-Semitism? What about Arab crimes? Syria? Iran? Weren’t we hypocrites? I was more surprised by criticism from the left. Why didn’t we mention Palestinian suffering? Was it true that someone who brought a sign criticizing Israel was told to put it away? How could we censor other Jews?

Important issues, every one. Estimates of Syrian deaths at the hand of the bloody Assad regime topped 76,000 last year. Europe’s Jews face random, brutal attacks in the streets of their own cities. Hope is in short supply in hearts from Gaza to the Golan.

Injustice, violence, despotism, hate — like Katrina, they hit everyone. But our rally was not about those issues, no matter how vital. Our sole aim in leading a Jewish protest was to march in solidarity with the movement insisting that #BlackLivesMatter, to stand with our black friends and family, Jewish and non-Jewish, whose lives have been disregarded, undervalued, and overlooked.

Americans are good at many things, but raising up the value of black lives isn’t generally one of them. Every time someone changes the subject to the crimes of Arab dictators, the subject isn’t the value of black lives. Every time someone changes the subject to Israel-Palestine, to Hamas or Bibi, the subject isn’t the value of black lives. And every time someone changes the subject to the purported hypocrisy or moral failure of one rabbi or another, the subject isn’t the value of black lives.

Our protest wasn’t about any of those things. It wasn’t about us. It was about Mike Brown. And Eric Garner. And Oscar Grant. And countless other black men and women, too many to list by name.

This week, Jews around the world begin to read the book of Exodus, the miraculous story of the oppression and liberation of the Israelites from Egypt. We would be shocked to hear complaints that the story omits the suffering of the Arameans or Philistines. We know the story is ours, a tale of Jewish deaths, and of Jewish lives. We know that is enough.

And so it was that our protest was about one thing, and one thing only. Our action was solely about the precious, infinite value of black souls. Can’t that, for once in this country, be enough?

It’s 2015. Will this be the year, finally, that we commit ourselves to protecting and nurturing those lives?

Rabbi Michael Rothbaum writes The Jew in the Street, a ZEEK column about standing up for justice.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Rabbi Michael Rothbaum

More articles in