Days of Future Past: Iranian Garage Rock of the 1960s

The other day I started thinking about the phenomena of Iranian garage bands while I was making dinner, trying to refine my thoughts on its political significance while my ten-year-old daughter worked on her homework at the kitchen table. I was preparing a vegetarian lentil dish, the sort to which I normally add a handful of very sharp chiles. But because she had expressed interest in trying my creation, after a lifetime of strenuously repelling all “mixed food,” especially the sort that is brown and soupy, I was striving to remove the Indian touches in favor of a generalized central Asian approach.

Some people think best in the office, some in the bedroom. For me, though, there’s something about the kitchen that puts me in an intellectual frame of mind. So as I was standing there at the stove deciding how much spice would still be too much spice for my daughter’s suddenly expanding palate, I was also musing on the relationship between taste and identity.

If we are what we eat, as the French writer Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin famously suggested in his 1825 book The Physiology of Taste then a sudden change in one’s food preferences must indicate a personal metamorphosis. Her openness to new sensations might not be a passing fancy, I speculated, but proof that she was passing to a new level of development. And that insight, in turn, directed me back to my consideration of Raks Raks Raks, a collection of Iranian garage band recordings from the 1960s.

We live in a reissue culture. Although there’s plenty of good new work being produced, the music industry is scraping by selling us the past in a new package. Frequently it comes in the form of remastered editions of our favorite records, usually with a selection of previously unreleased B-side sides, demos and live performances thrown in to sweeten the potential sourness of a deal in which we end up buying what we already have.

We are also being given the opportunity to purchase music that previously escaped our attention, from so-called “lost classics” that were praised by the critics and collectors lucky enough to experience them when they were obscure to collections that document the breadth of a long-vanished scene. But whether we are invited to revisit a past that was already part of our own history or become acquainted with one of which we were previously unaware, the underlying implication is the same: the music being produced now lacks something in comparison.

Whereas it was once the case that the rock and roll repertory was mostly populated by works that had stood the test of time, surviving the ebb and flow of musical fashion, much of the archival material being released today consists either of work that had been deliberately held back by artists because it was not deemed ready for public consumption – demos, alternate studio takes, flawed live performances – or work that failed the trials of the marketplace. Revisionist historiography is no longer the domain of experts who feel qualified to resist the judgments of the mainstream. All it takes to participate is decent internet access, the sort now found in most public libraries and schools.

That’s why it has become so much easier to find out about artists that were once deemed too insignificant or obscure to merit attention. So long as someone is sufficiently interested, they can create a website or Wikipedia entry for them. And more intense devotion can lead to resources as astonishing as Garage Hangover, a true labor of love created and maintained by one man, where you can discover – and download – garage rock from all over the United States and Canada, as well as a wide range of countries including Czechoslovakia, South Africa, Brazil and Malaysia.

Although there aren’t any Iranian bands on Garage Hangover yet, the tracks on Raks Raks Raks would be right at home. Like most of that site’s content from places outside of the American music industry’s major hubs, this infectious collection serves both to delight and instruct. The album isn’t simply fleshing out our sense of a music scene whose highlights are familiar to us, like Rhino Records’ wonderful box set Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets, 1965-1970 or its new companion Where the Action Is!: Los Angeles Nuggets, 1965-1968, but introducing material of which even most garage fans were completely ignorant.

As Raks Raks Raks’ extensive English liner notes indicate, this album is not marketed to Iranians. Nor is it intended to evoke nostalgia in the large expatriate communities in the United States and Europe. No, it’s a record meant for the sort of people with a hunger for world music and, what is more, the sort that defies those traditionalists who scour the globe for authentic native culture in its purest form.

It’s targeted at people like me, really, the kind who feel free to shift a recipe’s gastronomic associations from Kanpur to Isfahan without looking in a cookbook to make sure they are doing it right. That’s why I was pondering both whether to add more cumin and what it says about Persian cuisine that it’s relatively low on spicy heat. Could it be that Iran was more receptive to the countercultural savor of American garage rock than lands with a stronger native tradition of finding pleasure in what is outwardly painful?

The more I mulled this question, the more I retreated into the sort of speculative reverie that I eventually shape into more modest cultural analysis. It’s how I’ve learned to work. I start out thinking big and end up writing small, but with a secret desire to pack my sentences with enough hidden explosives to let the discerning reader blow up the limited arguments in which they are confined.

“Listen, Dad.” My daughter’s exhortation brought me abruptly back to earth. “Do you hear that? It’s ‘I’m a Believer’ in another language.” I’d been listening to the record so intensely that the clarity of her insight took me by surprise. “They’re singing in Farsi,” I replied, “the language they speak in Iran. That’s the place that used to be called Persia.” She nodded. “Cool.” And then she started singing along in English.

To be honest, I’m not sure she can find Iran on the map or knows why it’s in the news so much. She hasn’t yet shown much interest in current affairs beyond American politics. And they certainly don’t teach much geography or recent history in elementary school these days. But that didn’t stop her from taking pleasure in recognizing a song she knows transformed into an international communiqué.

Then again, the degree to which she is removed from the cultural context in which The Monkees’ original song was produced – after all, her forty-one-year-old father was born after its release – might make it seem like a message from a distant land. Because the 1960s are so regularly invoked in contemporary political discourse, it’s easy to forget just how long ago that turbulent decade was.

In one sense, the mere fact that my eleven-year-old daughter knows “I’m a Believer” well enough to recognize a cover version in an unfamiliar language underscores the fact that we live in a reissue culture. As the commercial success of The Beatles’ latest comeback in Rock Band demonstrates, the 1960s continue to sell in a way that the 2000s never could. But perhaps my own assessment of this phenomenon overlooks a crucial point.

Because I grew up in the shadow of the counterculture, I have seen its staying power in the marketplace primarily in terms of repackaging familiar content. For the youth of today, however, that material takes on a different aspect. I teach plenty of college students whose grandparents are Baby Boomers. To them, as well as younger children like my daughter, the 1960s take on the aspect, not of the recent past, but of the proverbial “good old days,” when computers were the size of a tank and the only mobile consumer technology was the transistor radio.

From this perspective, what the persistence of 1960s culture implies is less the inevitable byproduct of historical proximity than a collective impulse to translate memory into duty. “I was there, man,” that famous slogan invoked by Baby Boomers to reinforce their cultural superiority, has mutated into a demand that even those who were not there – and, indeed, couldn’t have been – remember what it was like.

And because it’s the popular music of that decade that is best suited for reminding us of its importance, songs play a crucial role in this ritual. Hearing the opening harmonics of Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth”, the carnival organ that kicks off Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “Tears of a Clown”, the serpentine guitar figure that leads us into the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” are enough to call forth a whole bank of images for us to bow down before.

As the philosopher Blaise Pascal famously declared, it is not the clarity of reason but the repetitions of “habit that makes so many men Christians; habit that makes them Turks, heathens, artisans, soldiers.” In short, it is habit that, “without violence, without art, without argument, makes us believe things, and inclines all our powers to this belief.” Regardless of their age or experiences, people who listen to these “classics” over and over end up becoming believers in the primacy of the 1960s. They learn to take it for granted that whatever has happened since must be routed, to some extent, throughthat decade in order to be understood.

Raks Raks Raks reinforces this call to return to the 1960s while expanding our sense of the decade’s cultural reach. That cover of “I’m A Believer” that my daughter recognized doesn’t simply convert the English lyrics into Farsi. Instead, the band Zia achieves added distance from its source by transposing the original’s 4-4 time into the 3-4 time – which sounds somewhat waltz-like to Western ears – that was standard in native Persian songs. The song thus serves as a tribute, not only to the appeal of rock and roll in Iran, but to the capacity of the country’s own musical traditions to withstand this cultural invasion.

Indeed, perhaps the most remarkable thing about this collection is how consistently the songs on it manage to sound simultaneously Eastern and Western. Even female pop diva Googoosh’s English-language cover of “Respect”, which steers clear of any obvious Persian touches, still makes the American song strange by coupling the pace and propulsive force of Otis Redding’s original version to Aretha Franklin’s slowed-down and spelled-out statement of female empowerment. Not to mention that the mere fact that Googoosh is singing this particular song at all reminds us that it was possible for her to raise questions about the status of women that would not be permitted in a post-revolutionary context.

Interestingly, Gökhan Aya’s fascinating liner notes for the collection – which develop an historical analysis that actually seems to benefit from his prose’s many ESL quirks – repeatedly make the point that the East-West hybrids it showcases struggled to make a commercial impact in Iran. Although Googoosh was wildly popular in Iran, the foreign-language EP on which “Respect” appeared did not do very well. Part of the reason was simply that Persian popular music never lost its luster, even among those Iranians most keen on embracing Western fashion.

And then there was the simple fact that the music fans who were most open to rock and roll usually preferred to hear international hits in their original form. “Trying to find a Persian way to rock,” Aya writes, “was seen as an unnecessary and an almost funny kind of task. Persian listeners who were into Western music commonly thought like, “When one could listen and boogie to the originals on vinyland radio, why bother with buying any local beat record, played by pretentious youngsters who are not that good players anyway?”

As the band biographies on Garage Hangover indicate, as well as the many intriguing garage-rock compilations put out by labels like Cicadelic Records and Collectables, most bands in the United States struggled with the same problem. In an era when airplay meant sales, the rapid increase in the number of rock bands during the mid-1960s heyday of garage rock made it increasingly difficult for even talented musicians to make an impression outside their own local scene. And geography often posed a major impediment. While a band in cities like New York, Los Angeles and London could count on playing in front of A&R reps, the chance of having that kind of access in places like Amarillo was remote.

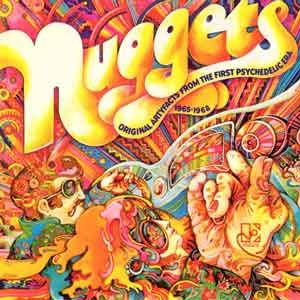

Nevertheless, young people continued to form bands. Even as the dream of making it big became less and less likely, the impulse to take matters into their own hands persisted. This is where the do-it-yourself culture made famous by the punk movement a decade later really got rolling. As Lenny Kaye writes in the liner notes to the original 1972 garage rock compilation Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968 – the first concerted effort to repackage garage rock for audiences that had overlooked its appeal – this music was launched into “a world in which youth felt they had too long suffered a pat on the head and a kick in the ass” by “kids who more often than not could’ve lived up the street, or at least in the same town” and were “seemingly more at home practicing for a teen dance than a national tour.” Although bands still sought commercial success, their greatest achievement was to demonstrate what could be accomplished with access to the means of cultural production without support from the state or culture industry.

In our own era, when millions of amateurs create and distribute cultural content each day, the example of garage rock shines brighter than ever. This helps to explain the music’s peculiar staying power, evident in both archival projects like Garage Hangover and the Nuggets series and the vibrant underground garage scenes in cities around the world. There’s a reason Raks Raks Raks is subtitled “27 Golden Garage Psych Nuggets From the Iranian 60s Scene.” Had it instead been labeled “Iranian Rock of the 60s,” it would have been less appealing to the kind of people who are still willing to pay money for recorded music. But the significance of the decision to invoke the terms “garage” and “nuggets” extends beyond the marketplace.

Like most of the countries where “garage rock” scenes have been retroactively discerned, Iran was not a country where many people actually had garages. It still isn’t. To imagine young Iranians hammering out tunes in a subdivision of three-bedroom homes with two-car garages is to indulge a fantasy that is simultaneously economic and political. Although everyday life in Tehran retains a cosmopolitan air, Iran has become a figure for the wrong kind of post-modernity, what happens when the forces of progress are vanquished by reactionary sentiment. We are drawn to the vision of an Iranian garage scene in the 1960s precisely because we perceive it as a future past. And we are drawn to Raks Raks Raks because it gives us hope that it is not a future past redemption.

It’s as though we were conceiving of the Iran delineated in these songs, a place where men want groovy Mod haircuts instead of beards and women can demand respect in the public sphere, as that child on the cusp of adolescence who is suddenly open to a whole new range of experiences, from mixed food to mixed company. We extrapolate from this youth culture what that land might have become if the Revolution had not intervened. It is telling, then, that Aya devotes much of his liner notes to destroying this narrative. “Persian rock of the 60s and 70s did not wane for conservative or such social reasons, but rather for much practical reasons coupled with being awash by the huge success of Persian pop artists,” he writes.

Nor was the impetus for change signaled by garage rock’s appearance in Iran was not at odds with revolutionary energies. “It’s very clear even for the superficial researcher that how Iranians have been ruled since the Revolution is not exactly how they wanted it to be in the days of the resistance. What mattered then was to throw the tyrant away at all costs (his passing away was announced as, ‘The biggest blood sucker of the century is dead’ on state radio) and the secular left fought against the shah hand in hand with the mollahs, two seemingly opposite world views mutually using their sources for wider support for the organization of the resistance.”

If we listen to Raks Raks Raks with the urge to redeem a future past, Aya suggests, our goal should not be to picture the highly stratified society of the Shah’s reign extended indefinitely but to imagine instead what would have happened if the secular left had prevailed in the wake of the revolution. The do-it-yourself culture we should be celebrating is not the one inspired by American style, but American political ideals. For that is the only way to give Googoosh the respect she calls for.

As much pleasure as this compilation gives, there is a terrible irony in the timing of its release. The popular uprising in Iran earlier this year was given little support by Western governments, despite the fact that many of its organizers self-consciously invoked the democratic heritage of pre-revolutionary progressives. Apparently, we find more appeal in the idea of Iranian hipsters than an Iran hip to our complicity in its decades of political bondage.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?