Waiting for the Monsoon: Howe Gelb Leads Us Through the Desert

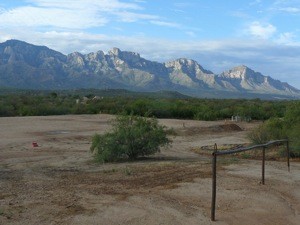

Only recently paved from start to finish, Park Link Road provides the sort of desert experience that decades of visitors to the Sonoran Desert have both openly desire and secretly feared. The region’s justly celebrated flora is on magnificent display, from the iconic saguaro cactus, particularly tall here, to the ironwood tree, which transcends the brush because of its regal bearing rather than its unimpressive height. The road meanders some twenty miles from the flat lands bisected by Interstate 10 to the foothills where different plant life starts to take over. Completed to improve freeway access for those who frequent Tucson’s northern suburbs, especially high-end developments like Saddlebrooke, plans for the road also appealed to developers eager to turn wilderness into profits. But with the state’s real estate market failing to climb out of the pit into which it fell in 2008 and the possibility that having a Democrat in the White House might make it harder to turn nature into easy money, the highway seems destined to remain a scenic rural drive for a while.

In short, the road traverses the sort of scenery tourists travel to Southern Arizona to see. Extrapolated for mile after mile, though, it exhausts the mind’s capacity to domesticate. The breadth of the vistas is daunting. But what makes the landscape along Park Link Road pulse with the terror of the sublime is more proximate. In most wilderness environments, the challenge is to find a passable route through. Here the problem is radically different. The landscape flashing by the car windows is replete with what appear to be trails separating one spiny plant from another. Despite appearances, however, the absence of vegetation does not reveal the path-breaking work of human beings. On the contrary, this labyrinthine negative space is the essence of the desert, overwhelming the viewer with roads not taken, a surfeit of possibility. The challenge that faces anyone who walks this land with a definite goal in mind is less to find the right way than to reject those that might lead to a bad end.

There’s something undeniably thrilling about the sense of possibilities such a landscape stirs within us. But it helps to have a guide. That’s why I decided to pop Giant Sand’s latest studio album, the beautiful proVisions, into the CD player as I made my way up Park Link Road one luminous afternoon. There’s nothing I like better than driving on a road without stop signs, listening to music. In this case, however, I was sufficiently struck by the uncanny quality of the scenery, its excess of functionally interchangeable “postcard” moments, that I needed musical accompaniment to humanize the sights. And who better than Howe Gelb, who has been capturing the feel of life in these parts for three decades?

A Jewish kid from the forest-rimmed industrial ruins of Scranton, Pennsylvania, Howe Gelb followed his father to Tucson in the late 1970s and discovered that the sense of freedom his new home gave him more than compensated for the burdens it imposed. Like migrants before and since, he found room in the desert to unfold all the oddly shaped parts of himself. Yet unlike most of the people who have adopted the Sonoran Desert, whether permanently or as a home away from home, he has also managed to translate his discovery into delightful instructions on how to trace a safe path through its hazards.

Whether in his primary band, the long-lived ensemble Giant Sand, his solo work or side projects like The Band of Blacky Ranchette, Gelb has somehow managed to make his adopted home both more familiar and more strange. To hear his music is to look out on the dangerous beauty of the landscape with a mixture of wonder and wry detachment, aware of how insignificant a human being seems compared to such epochal vastness but also understanding that making significance is what our species does best.

Maybe that’s why Gelb is wary of ever letting things get too serious. The path that seemed right one minute can turn out to be wrong the next. As he told me in a conversation from a few years back, “I kind of keep my ears and eyes open and figure it our as I go along, too, without making any hard and fast rules.” Improvisation helps to keep art from getting stale, but it also doubles as a survival skill. For the mind that stays open to new possibilities will be calmer in the face of crisis than one that is set in stone.

As the plight of illegal immigrants who cross the border from Mexico makes abundantly clear each summer, the state of nature in the Sonoran Desert is all too often a state of panic. Despite a century of being tamed by popular culture, the actually existing landscape continues to menace. Poisonous animals and plants abound. The slightest misstep can lead to a nasty wound. And then there’s the weather. Even in winter, unprepared hikers suffer dehydration, which can inspire irrational decisions, like taking a shortcut instead of a marked trail. In the middle of summer, heat stroke is a constant threat. A few years back, a fit young couple from out of state decided to make a quick June hike in Picacho Peak State Park, just north of Park Link Road’s western terminus, and ended up dying yards from their car, undone by the presumption that being able to see where they had come from and where they were headed was a sufficient safeguard.

That sad tale points to the profound lesson that too many travelers in this region learn the hard way. The sense of sight can exhilarate and inspire. But it can also trick you into taking the sort of risks that would seem ridiculous in a less open landscape. Mirages aren’t simply the result of objective conditions. The goal on the horizon also seems far easier to attain than it really is because of the viewer’s hubris. Survival in such a challenging environment demands a degree of preparation that residents of more sedate locales are likely to deem paranoid.

Take Park Link Road, for example. Let’s say you decide to pull off the road to take a photograph of a particularly stunning saguaro. In many places, the shoulder is soft and slopes abruptly away from the road surface. If you’re driving a conventional sedan, getting stuck is definitely a possibility. Now, assuming the day is clear and not too hot, this probably wouldn’t be too distressing. There’s enough traffic that someone would eventually stop to help. But if this were a summer day during the Monsoon season, the risks would increase considerably. Even major thoroughfares in the Tucson area are rendered temporarily impassable in the wake of big thunderstorms. And lightning strikes are common. Out there in the desert, miles from any homes or businesses, on a road that meanders through a floodplain, a lot of things could go majorly wrong.

Travelers from east of the Rockies have an especially hard time grasping just how easily the desert’s beauty can turn to menace. Steeped in the prejudices of European pre-history, in which the forest is identified with danger – and frequently evil as well, as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter famously shows – while clearings are identified with civilization, they struggle to comprehend how exposure can be a bigger threat than concealment. You can enjoy your Aufklärung here, in this place where the wonders of creation are excessively visible, but you’d better bring plenty of water and a wide-brimmed hat.

As its title suggests, proVisions represents a continuation of Gelb’s peculiar brand of rootsy psychedelia, in which surrealism undergoes musical transubstantiation into sustenance. When the capacity to see far into the distance can be a liability, insight frequently derives from supplementing the field of vision with details no camera can register. “Pitch & Sway,” one of the record’s stand-out tracks, directly addresses this question. “Way out on the horizon there’s a monsoon waiting,” it begins, “way out there beyond your eyes, son, there’s dreaded anticipation.”

In a climate where the skies are usually clear, the promise of a thunderstorm is exciting, not only for the rain it may bring, but the sights it will occlude. Indeed, the winds that accompany such atmospheric instability will do the job even when the dust doesn’t turn into mud. There’s danger in such bad weather, of course, but the sort that counteracts the danger in the good. “He’s been in command for so long now of all the defenses,” the song continues, “he’s been in command for so long now he’s taken leave of his senses.” In the desert, believing yourself to be in control may be the greatest form of madness.

Then again, the same could be said of the leaf-dappled suburbia of Connecticut or the rectilinear quaintness of Copenhagen. The virtue of the Sonoran lifestyle is that its uniqueness – many of the area’s noteworthy plants, like the saguaro, are native nowhere else – enables the perception of truths that apply around the globe. The current line-up of Giant Sand reflects this curious fact. Although proVisions sounds a great deal like the work Gelb recorded in the 1990s with Joey Burns and John Convertino before they left Giant Sand for their onetime side project Calexico, many of his current collaborators are from Denmark.

Since marrying a woman from that decidedly un-desert-like country, Gelb has spent a good deal of his time there, a circumstance alluded to in the song “Cowboy Boots” off his 2003 solo album The Listener. “The bread is good and so is the beer/If I’m still missing/You can find me here,” he sings in a breathy baritone mumble over music that splits the difference – like many of Calexico’s songs – between mariachi balladry and smoky jazz. “No matter how much I miss the Copper State/Poca Cosa and their relleño plate/I’m doing good work here at any rate/I’m a satiated expatriate.” That sense of satisfaction derives, not from having left Tucson behind, but the realization that he can – and, indeed, must – carry it with him wherever he goes. If musicians with no personal ties to the place can conjure it as effectively in Aarhus, Denmark as his former band mates did in Tucson’s barrio viejo, then its geographical specificity must be more portable than initially seems to be the case.

Part of the reason, of course, is that the Sonoran Desert is familiar to people around the world from its presence in Westerns. Indeed, there have been plenty of first-time visitors to the United States surprised to find that much of the country bears little resemblance to the Southwest. When Europeans refer to America as “the land of unlimited possibilities,” they aren’t thinking of an aging strip mall in New Jersey, but that mythologically sanctified realm where the only thing that separates you from the horizon is a wasteland waiting to be redeemed. For many people in the Old World, the United States was – and, to some extent, still is – the screen onto which fantasies of progress could be projected.

But if Gelb has benefited from this skewed form of cultural literacy, he has also contributed to its refinement. While American artists have long been able to succeed abroad even when commercial success back home escaped them, the internet has made it possible for audiences in distant lands to flesh out their musical knowledge with unprecedented speed and depth. Back in the late 1980s, when Giant Sand was first making its international mark, a reference to the relleño plate at Poca Cosa would have been very difficult for a listener in Glasgow or Osaka to pin down. Since use of the worldwide web became ubiquitous, however, such highly specific local color can be clarified with little difficulty. A truly dedicated fan could check weather forecasts, read the news, plot hypothetical hikes through the park lands surrounding Tucson, all without ever leaving the computer.

As salutary as this development may seem from a musician’s perspective – it’s nice to know that there will be fans at every stop on a concert tour capable of conversing intelligently about life back home – it also underscores the problem of easy familiarity that increasingly dominates contemporary life. When a half-hearted scan through the doings of your Facebook friends provides enough “personal” information to fill a Tolstoy novel, it can be difficult to remember that no amount of knowledge gleaned from afar can match the impact of seeing people and places in person. Increasingly, we treat our lives the way our iPods treat music, compressing the richness of experience until it has lost much of its special character. We might be able to store, sort and access more of our past that way, but at what price?

In early December of 2009, Gelb performed a benefit for Tucson’s Miles School at The Loft Theater prior to a screening of ‘Sno Angel Winging It, a low-fi documentary chronicling his recent collaboration with a Canadian gospel choir. The film was interesting, if perhaps a little hard to watch on such a large screen, but no match for the live show that preceded it. Playing both recent compositions and songs from deep in Giant Sand’s back catalogue, Gelb and a makeshift band featuring his current bassist, former drummer and the trumpeter from Calexico showcased both the strengths and weaknesses of his ramshackle approach to music-making, convincingly demonstrating that they are really opposite sides of the same coin.

What made the event special in a way that no digital distillation could convey, however, was what framed the performance. Parents and children from Miles School, which was raising money for its arts program, filled the crowd. Artwork for sale in the lobby served both as an additional fundraising opportunity and a way to demonstrate the value of the curriculum the benefit was intended to preserve. There were plenty of gray-haired veterans of Tucson’s post-punk scene in attendance, too. Sometimes, it was hard to tell where one demographic ended and another began. Gelb’s daughter attends Miles, as did John Convertino’s daughter, so playing the benefit required them to strike a balance between the habits of the anonymous concert hall with the peculiar pressure of playing for an audience familiar with their private lives.

Because Miles has a highly regarded special education program for students who are deaf or hearing-challenged, the performance featured sign-language interpreters who took on the unenviable task of communicating Gelb’s convoluted, pun-filled lyrics on the fly. At one point he paused, after a particularly surreal number, to apologize. But the interpreters pressed onward, imparting a new dimension to his work not unlike the sort featured in the film that followed, where a largely African-American and Christian chorus adds unexpected nuances to the songs of a decidedly secular Jew. As a whole, the event served as a powerful reminder of the good things that happen when people get together with one another, even if their destination is movie theater or dance club.

That sense of a traditional community, where the most important exchanges happen in person, saturates High and Dry, a 2005 documentary that relies heavily on Gelb’s input. Like other medium-sized cities, Tucson witnessed the growth of a rich alternative music scene in the wake of punk. Already a place where diverse musical genres came together in unpredictable and inventive ways, the local scene became increasingly self-reflexive about its special qualities in the Eighties and Nineties as independent artists proved increasingly willing to surrender the dream of making it big in Los Angeles or New York in the hope of making the smallness of Tucson “big.” In step with larger trends toward decentralization in American culture and the foregrounding of local color that has resulted, they found ways of turning the disadvantages of working outside the mainstream into strengths. Or at least that’s the story ably told by director Michael Toubassi’s film, which uses archival footage and interviews with participants in the city’s music culture to transform the fragility of personal memory into a more stable form of institutional memory.

Like other recent films devoted to local scenes that emerged in the punk era, such as the documentaries Made in Sheffield and American Hardcore and the partially fictionalized 24-Hour Party People, High and Dry is a worthy effort. It introduces newcomers to the music it covers with aplomb, inspiring them to seek out artists they would otherwise have overlooked, while also giving long-time fans a reason to renew their commitment to the scene. Unlike Made in Sheffield or American Hardcore, which focus on an era that has definitely passed, High and Dry brings its audience up to the present. This is one of the film’s strengths, both because this approach counterbalances the nostalgia for a better time that tends to afflict histories of popular music and because the feeling of continuity makes the past it conjures into a more effective resource for contemporary undertakings.

But the film also does an unusually good job of laying bare the problems that confront attempts to construct local cultural histories. The footsteps of one’s forebears are easier to follow if the prints are fresh. Yet there is also something confining about being presented with such a carefully plotted path through the underbrush of history. Foregrounding one particular line of development makes it harder for audiences to see how other outcomes might have been possible. While High and Dry does highlight moments at which participants in the Tucson scene might have pursued a different course, it still conflates chronological and aesthetic ends. It’s no accident that the film closes with a long look at Calexico, whose international success seems to confirm the correctness of the trajectory that the film charts from Tucson’s first punk shows, which were unapologetic attempts to copy what had already become passé in London, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, to the self-conscious deployment of local color that Calexico’s fusion of disparate musical genres exemplifies. The story High and Dry wants to tell, in other words, is a story about the advantages of staying home. It’s a compelling tale for anyone who has lamented the seemingly limitless expansion of the small-minded Big Box mentality to the far corners of the Earth.

According to the logic of the film’s narrative, home is less a place of origin than a destination. It’s a notion particularly appropriate for thinking about Southern Arizona, where illegal immigration is always in the news and its legal counterpart is a cornerstone of the economy. Among the artistically minded folks who populate Tucson’s alternative scene, the understanding that Tucson is a place where one ends up is widespread. The city has plenty of disadvantages for permanent residents, from the brutal heat of summer to the lack of jobs that pay well. But it has a way of making people who perceive the beauty in its outwardly barren appearance feel like they have found the home they were always seeking, often because it’s so different from the home they were fleeing. As Gelb remarked in our conversation, “The desert usually attracts people that want to live the way they want to live.”

Part of the reason is the terror its sublime geography stirs beneath the surface of consciousness. The realization that it’s easy to get hopelessly lost even when you can see exactly where you want to go, inspired by Park Link Road and other routes navigating the city’s rural environs, can make even a home without many creature comforts seem like the perfect shelter. In a long, illuminating interview published in The Village Voice on the occasion of proVision’s release, Gelb explains that he arrived in Tucson by accident, as a refugee of sorts, after his Pennsylvania home was washed away by a flood. “I ended up here and I probably would’ve never found my way here otherwise, or I would’ve taken the long way. And Dad lived here, so, you know, I came out here and it seemed like Mars and Mars felt good.”

Unlike those critics and fans who insist that there is a clearly defined Tucson sound – the implicit argument of High and Dry – Gelb, who would have to be one of its primary exponents, highlights the importance of the individual musician’s subjectivity. “I think it’s kind of like the music you’re ever going to make, or the art you’re ever going to make, is buried within you and it’s gurgling up and it has less to do with outside your skin than inside your skin. And if you’re lucky enough you find a place that’ll feel more like home because of it. And I think that’s what happened instead of the other way around.” Rather than being a function of particular stylistic choices, in other words, it’s because he ended up in Tucson that his music is identified with the place.

This is not to say that Gelb avoids all the indicators of local color. His fondness for shuffling rhythms, reverb-drenched steel guitar and lyrics that invoke the desert, like the reference to the Monsoon on “Pitch & Sway, all contribute heavily to the perception that he makes music in step with his adopted hometown. Unlike his former bandmates in Calexico, however, he doesn’t seem to worry about the consistency of that impression. On the contrary, while many of his songs conjure the landscape of saguaros and narcocorridos, others convey a different sense of place or, in some cases, placelessness.

Perhaps the best example of Gelb’s musical restlessness is found on the Giant Sand album that preceded proVisions, the aptly titled Is All Over the Map. The penultimate track begins with the sort of ruminatively jazzy piano that has become an increasingly large part of Gelb’s musical repertoire over the past decade. But then it gives way, abruptly, to a voice aggressively counting off “1, 2, 3, 4” followed by the familiar opening bars of the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK.” The song proceeds as a relatively conventional cover rendition for a while, albeit with the ideologically significant change that the singer is a woman. It peters out prematurely, however, yielding in turn to a short coda in which Gelb, deploying the exaggerated twang he sometimes uses for his “Western” number, detourns a pop-cultural classic by repeating the line, “Mama, don’t let your babies grow up to be Tolstoys.” Exhilaratingly random, the track more than lives up to its title: “Anarchistic Bolshevistic Cowboy Bundle.” While this might seem like mere lighthearted fun, the bizarre juxtapositions serve a deeper purpose, demonstrating Gelb’s belief that getting out of a groove may be just as important as getting into one.

From the countrified No-Wave conflagrations of his early albums’ fiercest jams to the preternaturally relaxed feel of the half-sung ballads he has favored in recent years, Gelb’s work has consistently demonstrated that rejecting the conventions of the mainstream need not mean confinement to one narrow aesthetic channel. Like the negative space of the Southern Arizona desert his wind-whipped compositions powerfully evoke, his music suggests both that there are many ways to get there from here and that the most direct routes, the ones proffered by the hubris of sight, might be the least desirable options.

Asked in that same Village Voice interview whether he should get any credit for the idea that there is a Tucson sound, Gelb offers a characteristically indirect reply about the relationship between culture and geography. Noting the “affinity for meander” that typified the city’s post-punk scene, he makes a clever pun. “I felt comfortable as a Meanderthal. Some folks have moved here since – good folks – and have less meander in their music.” Although he is too diplomatic to state it explicitly, he means Calexico – his former bandmates’ success stung him a bit – and other acts that have sought to emulate their brand of musical fusion, those who “have tapered it down and kind of maybe custom-fitted the local sound into more of a succinct scenario. And that’s okay. As long as they get their hands dirty now and again changing a cooler pad. I’m a little suspicious of any local band that’s never had to mess with their swamp cooler or change their own pads.”

An oblique reference to the “Snowbirds” who flock to Arizona in winter only to flee to their “real” homes when the heat sets in, this statement also makes a cogent point about class. It’s not enough just to summer in Tucson. If you can pay someone else to do the work necessary to survive the extremes, you haven’t really made it your home. Because the true measure of local color in the desert is whether it has been sanitized or left “dirty from the rain,” as one of the finest songs on Giant Sand’s 2000 album Chore of Enchantment puts it. Here, too, clarity invites confusion, while indirection has a way of making things clear. Home, Gelb, suggests, shouldn’t mark the spot where you think you have everything figured out. Whether you end up in Denmark or the desert, the point is not to fix the routes on your mental map but to learn how to keep selecting different paths without getting lost. It’s an exercise that demands attention to detail, surely, but also an understanding that the facts are bound to shift with the dust stirred up by the storms of fate.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?