A Chill To Warm the Heart: Mark Glanville and Alexander Knapp's A Yiddish Winterreise

In the wake of the Holocaust, the German classical repertoire has created an obvious dilemma for Jewish musicians. To reject it altogether, as some have done, means professional marginalization. To embrace it the way so many assimilated Jews once did, however, can seem like a willful refusal to remember. All manner of compromises have taken shape in the territory between these two extremes, from those who prioritize the work of Jewish composers in the classical tradition, such as Mendelsohn and Schönberg, to those who painstakingly sort the good Germans from the bad, to those who blur the distinction between “high” and “low” culture as a way of recuperating Ashkenazi traditions. Regardless of the approach taken, there is no easy way out of this dilemma. But the remarkable Yiddish Winterreise shows how much melancholy beauty can be discovered during the search.

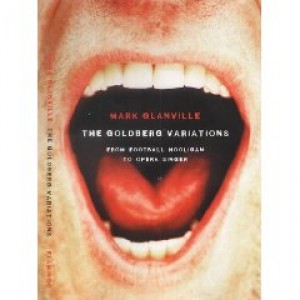

The product of an intriguing collaboration between Mark Glanville, who wrote the widely praised book The Goldberg Variations about his days as a teenage football hooligan in London, and Alexander Knapp, an expert on Jewish music, Yiddish Winterreise reminds us that the language of the shtetl is not that far removed from the language of the German countryside. In turning away from the rituals of the court in favor of more rustic inspiration, nineteenth-century German composers like Fran Schubert elevated the folk ballad to the same status as more sophisticated compositions. Indeed, the Lieder found in song cycles like his celebrated Winterreise make the distinction between simple and complex forms seem irrelevant.

So does Knapp and Glanville’s creation, though in a different emotional register. Although studded with moments that recall the dissonance of twentieth-century New Music, most of the songs derive their modernism from the wellspring of tradition. Knapp’s arrangements demonstrate that the “off” notes that Schönberg and his followers turned into a system derive, in part, from the minor-key wistfulness of Ashkenazi songs. In his supremely capable hands, even familiar Yiddish numbers acquire an avant-garde patina. The same goes for Schubert’s own “Der Lindenbaum” from Der Winterreise, repurposed here as “Di Lipe.” There is Romanticism here, to be sure, but the sort that emerges, psychologically battered, from the ruins of secularism’s future.

In the original Winterreise, the conceit is that the songs trace the emotional undoing of a man who has lost his lover. Yiddish Winterreise turns that tale of amour inside out, reimagining it as the grief of a father who has watched his child perish. But because Knapp and Glanville periodically make room in the darkness for the light of youthful laughter, the work as a whole feels strangely hopeful. In a sense, their song cycle performs the work of mourning rather than merely pointing to the need for it. Against this backdrop, the a cappella “Kaddish” that closes the record results in a deep sense of peace. This is profoundly beautiful music, worthy of the high accolades that are starting to stream in. You owe it to both yourself and your heritage to hear it.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?