All the Taste Without the Flavor: Charlotte Gainsbourg's IRM

It’s really hard not to like IRM, Charlotte Gainsbourg’s collaboration with Beck. From the 60s-ish folk pop of “In the End” to the worldbeat-fortified propulsion of the French-language “Voyage”, the record deftly traverses a wide range of musical terrain. And Gainsbourg’s distinctive voice, which seamlessly integrates breathiness and grit, applies a common patina to songs that might otherwise sound like selections from a mix CD.

Listeners can easily shift from focusing intently on the music to treating the album as background, a pleasant soundtrack for everyday tasks. But the music’s eagerness to please, its insistent likability, is also what makes it unlikely to become essential to anyone’s collection. In its eagerness to appeal to a broad audience, IRM makes itself almost as difficult to love as it is to dislike.

Like Hollywood blockbusters that reflect the influence of demographically diverse focus groups, IRM seems too aware of the rewards to be reaped from failing to offend. Ironically, Gainsbourg’s best-known musical work prior to this record was a duet she and her father Serge cut back in 1984: “Lemon Incest.” Charlotte, who was twelve at the time, pants her lyrics in a register so high that it’s normally reserved for non-semantic content while Serge offers louche counterpoint in his best Barry White. And the video, even more over-the-top, features the scantily clad father and daughter in bed together.

While the disturbing specter of pedophilic incest is bound to absorb most listeners’ attention, that’s not the only reason the song is in poor taste. By wedding a disco beat to a lovely Chopin tune, “Lemon Incest” brutally transgresses the aesthetic class divisions that even now remain a crucial aspect of European life. Perhaps that’s why the song was so successful in France. Even though it’s often painful to the ears, this curious novelty is supercharged with the energy released when repulsion is mobilized for artistic effect.

Given the number of subgenres that IRM touches upon, it’s certainly possible that Gainsbourg conceived of the album as a sophisticated update of this approach. The problem, though, is that individual songs don’t go far enough in their masquerades to evoke true disgust. Even the title track, with its invocations of both the psychedelic Beatles and Portishead, keeps its shuffling beats and industrial noises sufficiently suppressed to avoid alienating all but those rare listeners – usually past retirement age – who never reconciled themselves to rock in the first place.

The same goes for “Trick Pony”, which turns up the volume but makes sure never to stray too far from the conventions of the electrified blues. “Vanities” and “La Collectioneuse” hearken back to the soundscapes that chanteuses like Marianne Faithful, Nico and Laurie Anderson were fond of putting words over, but without the awkwardness of delivery that made the latter’s work stand out from the crowd. In short, IRM is relentlessly palatable.

This is not a derogatory judgment. Soothing music has an important function, even for provocateurs. But the fact that IRM does such a good job of sanding down the edges of daily existence tells us a good deal about the relationship between popular music and taste in the contemporary marketplace. The subgenres the record draws upon, its artistic genealogy, testify that it was constructed to have maximum appeal for members of Gainsbourg and Beck’s generation.

Or, to be more precise, that portion of that generation reluctant to acknowledge that hip-hop has supplanted rock as the dominant form of expression in contemporary popular music. It’s a record, in short, tailored primarily to the white, bourgeois, privileged demographic that has yet to displace the Baby Boomers from positions of social and economic power. Already middle-aged, yet without having achieved the security of equaling their parents’ achievements, the people who fall into this category are in need of a confidence boost or, failing that, at least something to wash their unease away.

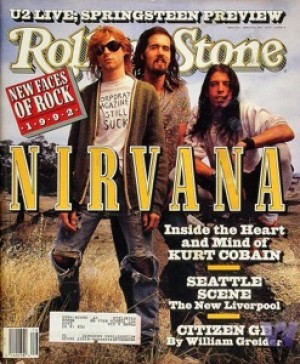

While that was already the case two decades ago, when the shadow of the 1960s dominated both cultural and political life, back then their hope for radical change was still buoyed by the shortsightedness and swagger of youth. The teens and twenty-somethings who bought records by Nirvana, Liz Phair and Pavement – not to mention Beck himself – back in the 1990s were flush with the conviction that they were helping to bring popular music out of the wilderness of inauthenticity in which it had wandered through the hairspray and spandex-textured hegemony of the Reagan Era.

To be sure, they gloried in their “alternative” music’s disruptive potential. But what they wanted to disrupt was first and foremost an aesthetic order. Bad taste had dominated the airwaves for most of the previous decade. Now it was time for excellence to be restored to its rightful place on the throne, as had been the case in the heyday of The Beatles.

And, at least for a little while, their wish was granted. By the end of the 1990s, though, the mainstream was once again dominated by the sort of music that dismays connoisseurs of “quality”. From boy bands to Puff Daddy, from Live to Celine Dion, the days when Nirvana had topped the charts seemed very far away indeed. That’s one of the reasons why the thirty-somethings of the 2000s were able to wrest cultural compensation from the horrors of the post-9/11 era. Slowly but surely, music they recognized as good started to make its way back into the mainstream. The difference was that this was less a return to the airwaves than an occupation of the distribution channels that had replaced them: the display racks at Starbucks, television commercials, film previews.

The prime explanation for this resurgence of good taste was that the closed circuits of the culture industry had been blasted apart by digital downloading. When discovering new music does not entail a large financial burden, people are more likely to be adventurous in their choice of listening material. But the fact that fewer people were purchasing music also skewed the charts away from the youth market. Modest Mouse, Neko Case, or The Arcade Fire may have been debuting near the top, but overall sales weren’t even close to where they had been when Nirvana seemingly came out of nowhere to go multi-platinum. The situation resembled, though for different reasons, the historical development of jazz.

Up through the Big Band era, much of what was sold under that label was the definition of bad taste. As rock and roll supplanted jazz as the primary form of popular music for young people, that “bad jazz” largely disappeared, giving way to more challenging but less lucrative artists who appealed to a smaller, more devoted audience. Within the context of that significantly reduced market share, the only way for a jazz artist to make it big was to produce music that satisfied both hardcore fans and casual listeners who might buy an album or two to stand in, metonymically, for the collection they didn’t have the time, money or inclination to assemble. That’s why Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue has had consistently strong sales since it debuted over five decades ago.

It would be perverse to argue that Kind of Blue, regarded by almost everyone as a masterpiece, was conceived as an attempt to maximize audience share. But there’s no denying that Davis and his collaborators succeeded in recalibrating the virtuosity of hard bop so that it could be enjoyed by people who didn’t want to think too much about what they were hearing. Nor is there any question that this milestone recording appeared towards the tail end of jazz’s transformation from youth culture into a culture centered on the denial of youth. By the 1960s, listening to jazz had become a way of signaling one’s sophistication and maturity. If young people sought the music out, they did so precisely because they didn’t want to be identified with the rock and roll favored by their peers. And older fans clung to jazz as a way of reinforcing their sense of generational solidarity

For all of its tasteful satisfactions, IRM will clearly never approach the stature of Kind of Blue. But it does nearly as good a job of responding to prevailing market conditions. A person could make the album their sole rock purchase of 2010 and still come away with a decent sense of where rock has been and where, in its steady decline, it is headed. What they would not be able to get from the record, though, is a sense of why and how rock mattered in the first place. This was once music, after all, that simply refused to be shoved into the background.

Music that drove teenagers into the garage or industrial practice space. Music that made someone call the cops. Music that made you feel alive even when it annoyed you or, like “Lemon Incest”, made you shiver with the specter of unspeakable transgression. IRM, by contrast, represents the dissolution of the boundary between rock and ambient music. In a way, it’s like muzak, only without the unsavory aftertaste. You can make love, doughnuts or flowcharts to it. Just don’t ask it to change your life.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?