Cultural Shiva? What It Means To Mourn a Popular Musician

When I first learned that musician Alex Chilton, of the bands Big Star and the Box Tops, had died last Wednesday, I distanced myself from the news. In response to the obituary a friend had posted on Facebook, I wrote something that now seems distressingly flippant: “Boy, it’s like the apocalypse for my CD collection. I sure hope everyone in Pavement stays healthy before I see them in June.”

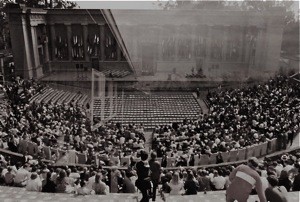

Mind you, that really was the first thing that popped into my head. I have been looking forward to witnessing my favorite band’s reunion tour ever since their first New York shows were announced. If all goes well, I’ll be seeing them in Berkeley’s Greek Theater, the place where I walked in my college graduations. And I’ll be accompanied by the same longtime friends with whom I first discovered the band’s charms back in the early 1990s. It’s a big deal for me.

But my comment was still callous, the sort of careless quip that people make when they aren’t considering the feelings of others. The irony is that I was also ignoring my own feelings. The more I thought about it, the more obvious it became that my apprehension wasn’t just about an eagerly anticipated concert.

It has been a difficult month for my family. My mother was rushed to the hospital after a bad fall on her wedding anniversary February 19th and hasn’t been home since. When I first got the bad news, I left the conference I’d been attending in Louisville and drove my rental car all night to the Washington D.C. area to see her. After several days of steady improvement, I flew back to Tucson to deal with parental and professional responsibilities. But my mother then went on to suffer a series of setbacks, making it necessary for me to fly back east earlier than expected.

Right before I made that second trip to see her, I learned that Mark Linkous, the mastermind behind the band Sparklehorse, had killed himself. I had long been a fan of his music, an affection further reinforced by his recent collaboration with DJ Danger Mouse and David Lynch on the superb Dark Night of the Soul project. Normally, I would have done my best to honor his memory by listening carefully to his work. But because I was frantically packing for an unexpectedly rapid departure, the best I could do was to vow that I’d celebrate his legacy when I returned to Tucson.

And that ritual was still on my to-do list last Wednesday when I heard about Alex Chilton’s passing. Coupled with the December deaths of Vic Chesnutt and Memphis garage rocker Jay Reatard, which the pre-holiday rush had forced me to defer, I now had a great deal of mourning to catch up on. That’s more or less what I had in mind when I wrote of “an apocalypse for my CD collection.”

It also helps to explain why my first response to Chilton’s death seemed so shallow. One thing that spending day after day in the hospital reminds you is that human beings have a limited capacity for emergencies. No matter how dire the situation, no matter how depressing the surroundings, we settle into a routine after a while.

When my brother-in-law first telephoned me in Louisville, I was in such a state of shock that I nearly walked through a plate glass window. Even after I’d collected my thoughts enough to plot a course of action – driving all night rather than trying to fly on short notice at exorbitant cost – and set out on the wintry drive through Appalachia, memories of my mother would still flash through my mind periodically like a DVD being fast-forwarded at quadruple speed. Every hour or so I had to stop the car and walk around in the frigid air in order to regain my focus on the act of driving.

A few days later, though, I was measuring out my life during the breaks in between ICU visiting hours. And instead of confronting the almost unbearable decisions my mother’s condition seemed likely to force upon us, I preoccupied myself with the dizzyingly diverse potato chip selection at the hospital café: salt and vinegar, cheddar and horseradish, sour cream and onion, honey and mesquite barbecue, Buffalo wing etc.

By the time I was in the middle of my second trip to see my mother, I even found myself contemplating such mundane concerns during medical crises: what flavor should I try next? Although I could still articulate the gravity of the situation, something had redirected the pressure it was exerting on me to a place where its effects were more diffuse.

In retrospect, that same mechanism was clearly at work Wednesday when I learned of Alex Chilton’s death. While the connection between life-and-death family matters and entertainment might seem tenuous, whatever it is that anaesthetizes me in times of fear and sadness clearly extends from one domain to the other.

That realization has prompted me to reflect on the social uses of popular culture. If the mind is capable of defending against loss in the same way whether it be proximate or far removed from our personal lives, maybe our reaction to the misfortune of celebrities is more complicated than it initially appears. Could it be that we cultivate attachments in the public sphere, not only as a means of escaping reality, but of preparing ourselves to confront the blows it inflicts on our psyche?

In a broad sense, this is another version of a question that has been asked of art since Aristotle. But I don’t think its specificity is insignificant. Although the way audiences respond to a tragedy played out on a stage or screen may seem identical to the way they respond to one that occurs in the real world, there is still a difference between mourning a loss that is part of a story that can be repeated over and over and one that only comes once.

We can identify with the first person singular in a song that Alex Chilton or Mark Linkous have written to the point where we collapse the distinction between the performer, his persona and ourselves. However intense this experience may be, however, sane people retain the capacity to recognize that happens in the song is not subject to decay. Individual works of art may be lost or destroyed, but in the abstract, as the poet John Keats famously communicated, art has no expiration date.

It used to be that I would pay little mind to the tabloids at supermarket check-out counters. Once my daughter started reading them, though – she recently turned eleven – I began to appreciate the important role they play in contemporary society. Fascination with the real lives of artists is nothing new, of course. But the relentlessness with which today’s celebrities are revealed to be fallible imparts a different aspect to this interest.

In a world where thousands of people take perverse delight participating in celebrity “death pools” and the trials and tribulations of famous people can even seem more popular – see Tiger Woods – than their triumphs, we need to supplement traditional conceptions of art with an understanding of its relationship to the “non-art” of everyday life.

Art doesn’t go away just because artists are rudely displaced from their pedestal. On the contrary, its appeal typically increases as a consequence. The massive media frenzy that surrounded Michael Jackson’s death last year may have been unseemly, but the resurgence of interest in his music that accompanied it cannot simply be written off as a case of cultural rubber-necking. Indeed, whether the people who sent his albums back to the top of the charts were long-time fans rediscovering their affection for his art or newcomers drawn in by the spectacle of his death, it is clear that his work benefited enormously from the public mourning that thrust it back into the spotlight.

And I don’t just mean this in a financial sense, although the impact of his passing on the marketplace was stunning. Because it was impossible to think about his art without also pondering the “non-art” of his troubling life story, listeners were able to extract nuances from his music that had previously escaped them. Even the superficially frothy numbers of his youth acquired a gravitas that made them sound simultaneously like celebrations of the present and premonitions of a dark future.

Although I had never been much of a fan of his work, favoring Prince’s sexed-up aesthetic to Jackson’s seeming aversion to physical contact, I still found myself moved to undertake my own rediscovery of his music. When I started roller-skating at a rink with my daughter and her mother, I found myself repeatedly intrigued by both the frequency with which tracks from Off the Wall and Thriller were thrown into the otherwise contemporary mix and by the way they always seemed to boost everyone’s pace.

I thought again of that strange thrill of hearing Jackson’s music in that context, amplified by the novice skater’s fear of taking a tumble, as I sat Wednesday night feeling bad about my initial response to Alex Chilton’s death. Maybe all the time I’d been spending in the hospital with my mother had impeded my ability to be stimulated by loss. Maybe I was afraid of what I’d learn if I permitted myself to indulge the sort of reflection that had come easily the previous summer when the news of Jackson’s sad demise first broke.

Even as I second guessed myself, though, I found it both difficult to move and difficult to be moved. After making several attempts to write something about the “apocalypse for my CD collection,” I ended up simply lying down in the front room, paralyzed by indecision. Before too long, I fell into the sort of restless sleep that comes when the absence of consciousness becomes an end rather than a means.

And then I suddenly sat up, without the tediously drawn out waking that I usually go through, and listened to Big Star’s first two albums in the dark, without interruption. Maybe it was the lack of visual interference, but the experience was of a nearly hallucinatory intensity. Three-minute songs seemed to last three hours. Details I’d never discerned before, despite hearing the albums hundreds of times over, suddenly impressed themselves upon me with tremendous force. Music I’d always loved, that was a mainstay of my record collection – as it was for so many people who share my affection for alternative rock – was transformed into a conduit for feelings so powerful and close-to-home that the statement “I love this song” seemed hopelessly shallow.

After this private mourning, I finally felt capable of publicly acknowledging Chilton’s death in a more serious manner. Even though it was already well past 2am, I dragged myself over to the computer and searched his name on YouTube. For the most part, I already knew what I would find. Indeed, I had already sought out many of the most frequently played clips on previous occasions, when a sudden rush of Big Star euphoria had driven me to supplement their three studio albums with other content. What I wanted, more than anything, was to see that other people were engaging in the same activity.

Just as was the case when Michael Jackson had passed away, Alex Chilton-related clips were enjoying a huge boost in popularity. The numbers weren’t equivalent, mind you. Jackson was the world’s most successful recording artist and Chilton only a cult favorite. But the process, that sense of a ritual mourning conducted in public, was exactly the same. Not only were fans posting comments on Big Star and Box Top videos, they were also seeking out versions of the Replacements’ song “Alex Chilton” and paying voluminous tribute there.

In the end, although I had the urge to repost dozens of clips in his honor, I restricted myself to two. The first, initially released by The Oxford American, a magazine I’ve written for, was one I had already watched many times over. It features home movies of the band from 1971, most shot in and around their native Memphis, to the soundtrack of their beautiful song “Thank You Friends.”

I’m a huge fan of behind-the-scenes footage, particularly when it features an artist I love. And the song has always struck me as one of the best expressions of gratitude in popular music history. What struck me this time, though, were the shots of a Braniff International jet. This seemingly incongruous element, having nothing to do with the band per se, communicated the loss I had initially warded off with a force so great it brought me to tears.

Braniff, one of the first casualties of airline deregulation in the United States, ceased operations in 1982. But the look of its planes, whose fuselages were painted bold colors like orange, turquoise and lemon yellow, made a huge impression on me as a child. I distinctly remember watching Braniff planes taxi and take off with my mother and father, their distinctive appearance giving life to the gray skies of winter, just as the Big Star home movies in this clip show.

Someday I’d like to explore the sort of nostalgia that the sight of the Braniff jet triggered more fully. There’s something Moebius strip-like about the way it relocates Big Star’s music, which I didn’t discover until my college years, into the domain of childhood memory. Even though I didn’t hear the song until I was legally an adult, the clip transforms it into a soundtrack for the fragmentary, visceral recollections of pre-school.

Maybe it’s that sort of mental alchemy that led the playing of music to be forbidden when sitting shiva. While a song may intensify the emotional weight of mourning, there’s a good chance that it will displace listeners from contemplation of the dead person and redirect them to think of their own “dead,” past experiences that can only be accessed through the mechanism of nostalgia.

If that is the case, though, perhaps the rituals that music lovers perform upon the death of their favorite performers should be granted an exception. Unless you have known a musician personally, the only way to undertake the work of mourning is to reacquaint yourself with their work. To forbid listening to music in that context would require playing it back in your head, an exercise bound to create more distance from the artist being mourned.

Then again, it may be that the very idea of sitting shiva for someone you don’t really know is wrongheaded from the get-go. The fate of tradition in the era of mass culture is complex, with new forms of expression radically expanding our knowledge of individuals, even as the circle of people we know well diminishes. Mourning someone we never met or someone who is only a casual acquaintance, as sites like Facebook make possible, could drain energy that might be better spent minding family and friends with whom we have a bond that isn’t only mediated by technology.

Although I take these reservations seriously, however, the difficulties of my past month have led me to adopt a more flexible attitude. In initially refusing to acknowledge Alex Chilton’s death with the care my love for his music merited, I was acting out my resistance to confronting my mother’s condition directly. And when I suddenly woke up and began to perform the work of mourning I had previously deferred, the intensity of my feelings was greatly enhanced by my sadness at her current state. Yet I don’t think this psychological bait and switch was counter-productive. I needed an outlet and reflecting on Chilton’s career, as well as that of other musicians who had recently passed away, gave me one.

The second clip I chose to share, a cover of one of my favorite Beach Boys songs, was the one that finally brought me to tears. Maybe because I hadn’t heard it before, yet knew the song so well, it managed to penetrate recesses that repeated listening had rendered inaccessible. Or maybe it was just that the lyrics, about longing to be older, seemed so poignant in the midst of meditation on the loss of youth.

At a time when most listening proceeds under the sign of distraction, with music frequently reduced to the status of Muzak, taking time to really concentrate on a body of work can have profound consequences. Since Chilton’s death I have found a way to revisit those memories of my mother that were coursing through my head so rapidly on February 19th and turn them into a kind of mental movie that I play over and over as I contemplate her role in my life. While it may not constitute a direct engagement with my sadness and fear, the psychological state it brings about is clearly preferable to outright denial. I am allowing myself to feel in a way that I might never have managed without the mediation of music I love.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?