A Tale of Two Karkadans: Music in Multicultural Europe

Searching for the music of Karkadan on the internet is an unsettling experience. Some pages turn up a metal band that identifies itself with both the “progressive” and “death” subgenres. The band’s deliberately low-fi official video for the song “Ancient Times”, with its archival footage of destruction from the Second World War, gives a good sense of their bleak aesthetic:

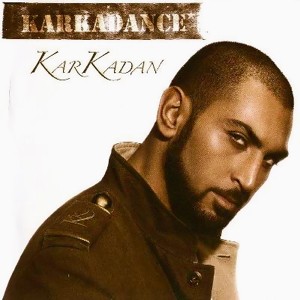

And then there is the other Karkadan, whose video for “Discoteque” has a decidedly different feel:

It’s hard to imagine two more different artists in the realm of popular music. Yet the linguistic confusion that arises from their shared name directs our attention to what they have in common: a Europe in which a Persian term for a mythological, one-horned beast seems equally attractive to long-haired Germans from Stuttgart and a rapper of Tunisian descent who makes his home in Italy.

Both names are examples of what Edward Said famously called “Orientalist” discourse, but with a crucial difference. While the German group’s use of the name “Karkadan” represents the psychological plundering of a faraway culture, the rapper collapses the distance between East and West. His beast has escaped the storybook to wander the streets of once-staid cities, signaling that the terror of “ancient times” has once again become flesh.

Or maybe the rapper is just making fun of such portentous implications. Watching the video for “Discoteque,” it’s difficult to tell how seriously he wants us to take it. From the exaggerated shimmies of his scantily clad female companions to the oversized disco ball, numerous details convey the impression that this “Original Fan” – the appositive with which this Karkadan distinguishes himself from his German rivals – might be out to parody American hip-hop stereotypes. And the bemused look on his face as he lips syncs to his electronically distorted vocals only reinforces this sense.

At the same time, it’s possible that “Discoteque” is simply pure mimicry, that the originality of his fandom pertains to chronology rather than creative license. It has been a long time since mainstream hip-hop was dominated by the discourse of authenticity. The use of Auto-Tune, both to transcend the imperfections of the human voice and to transform it into something that sounds deliberately inhuman, is an index of a broader trend, in which fakery is exalted at the expense of the real.

Karkadan the rapper doesn’t simply use this technology in “Discoteque,” where its presence could be interpreted as an implicit commentary on the current state of hip-hop. Auto-Tune is all over his album Karkadance, even when his vocals sound more fierce than fun. On tracks like “Capo” and “Famma Illi,” where his multi-lingual spitting could strut proudly without any computer enhancements, the distortion softens the impact of his words considerably.

Maybe that’s the point. The sonic embellishments on Karkadance may make it hit less hard, but they also give it the sort of crossover appeal that leads to hits. The sampled guitar chord that underpins “Capo”, the wheezy funk bass line on “Disco”, his collaboration with Marracash, and the acid wash Duran Duran shuffle that propels “Millionaire” all invoke the first half of the 1980s, an era when “overproduced” music possessed both mass appeal and alternative caché. Not coincidentally, this was also when hip-hop began to make the move from being an underground, inner-city pleasure to a worldwide phenomenon and also when metal subcultures began to part ways with mainstream rock.

Because the rapper lives in Italy, where the backlash against such processed sounds was slight, these touchstones don’t come off as exercises in nostalgia. Rather, they represent nods to a largely unbroken tradition, one sustained in discotheques and dance charts regardless of what was happening in the United States or Britain. Were this a purely instrumental record, it would barely make a ripple.

What makes Karkadance sound so fresh is the way it weds this fundamentally risk-averse musical approach with words that signal the rise of a new multicultural consciousness. Moving fluidly from Arabic to Italian, French and English, the “Original Fan” draws attention to the outdatedness of the political language with which most white Europeans still seek to comprehend their world. The German metal group may be trapped in the past, a time when Persia felt as remote as Middle Earth, but they have plenty of company.

In a way, trying to determine how tongue-in-cheek Karkadan’s work is misses the most important point. By constructing a space in which indeterminacy prevails – sincere or parodic, light-hearted or angry, Arab or European – his music has the potential to make listeners question the answers they take for granted. Put another way, this is culture about what it means to inhabit what some have called “Post-Europe,” a place where regional and national identities are complicated by the flows of temporary and permanent migration.

What happens in such a mixed-up land? Progressives may dream of a state of harmony, where the karkadan lies down with the lamb. But the short-term consequences are much more likely to result in the political equivalent of a high-school lunchroom, where cliques stake out their territory and the communication between them is minimal. In other words, what results will be a place where Karkadan the German metal group and Karkadan the rapper will sit at different tables, sometimes coming into conflict, but usually acting as though the other simply doesn’t exist.

Still, within the disunity of the high-school lunchroom, some kids will be more popular than others. And some of the asymmetry will be due to factors largely beyond individual control, like personal appearance or reputation. Nevertheless, popularity also depends partially on a willingness to reach out to others. From that perspective, the rapper Karkadan’s concessions to the history of the European discotheque are not just a savvy commercial move but a profound political gesture.

So is his tribute to the American boxer and global icon Mohammed Ali, though for different reasons:

To be a person of Muslim descent in contemporary Europe is not easy, particularly in Italy, where multicultural consciousness lags decades behind the sort found in Germany or Great Britain. As the crossover-friendly quality of Karkadance amply demonstrates, the rapper wants a bigger audience than his expatriate subculture can provide. But he also recognizes that sustaining that subculture requires the existence of a network of solidarity extending far beyond Europe’s geographical limits.

Although Mohammed Ali never stopped identifying himself as an American, he also identified himself with a global community in which international brotherhood takes precedence over local and national concerns. In recalling this legacy, the rapper Karkadan may conjure the specter of the internationalist ethos that inspires anxiety among white Europeans, the suspicion that the continent’s Muslim population will never be fully contained by its psycho-geographical boundaries, but he also provides the tools for all the continent’s inhabitants, including anxious whites, to reimagine themselves as citizens of the world as well as members of the European Community.

Maybe that’s a goal that the German metal group Karkadan also shares. After all, the fan base for their kind of music is both limited – it will never achieve the kind of popularity that contemporary hip-hop has attained – and international. The problem is that it promotes such solidarity at the expense of inclusiveness. Clearly, not all European bands that identify themselves with “death metal” are racists. But the fact that some of them do profess to “purity” brands everything that is linked with the subgenre. And that makes outreach to other demographics difficult indeed.

Nevertheless, it’s worthwhile to imagine what such an effort might yield. Back in the early 1990s, when mainstream American music was fragmenting into genres that seemed to have little in common, the soundtrack for the otherwise forgettable movie Judgment Night performed the remarkable feat of getting alternative rock and metal bands to collaborate with hip-hop acts. Slayer paired with Ice-T, Sonic Youth with Cypress Hill, Biohazard with Onyx , Teenage Fanclub with De La Soul and Faith No More with the Boo-Ya Tribe:

Even if the results were a mixed artistic success, the overall effect was decidedly utopian, suggesting that the anti-establishment energies mobilized in the wake of the 1992 uprising that followed the Rodney King verdict might be organized into sustained political opposition. Those hopes were soon dashed, as the Clinton Presidency lost its way amid right-wing assaults and the scandals they fueled. But now, with the benefit of hindsight, we might ask whether the spirit of that Judgment Night soundtrack didn’t return in the excitement of the American political campaigns of 2008 and the subsequent realization that, however fierce the resistance of reactionaries and closet racists, the nation had achieved a degree of multicultural consciousness that could not simply be undone with a backlash vote in elections to follow.

Returning to the two Karkadans, it is at least worth asking what it would take to create the circumstances for a collaboration between them. What if, instead of walling themselves in behind their own fear and prejudice, more white Europeans reached out to the impoverished immigrant communities that now cover the continent, seeking ways of working together instead of staying apart? What if members of those communities in the banlieues and Council Estates were able to overcome their sense of isolation and despair and find new ways of partnering with both the traditional and post-structuralist Left?

As depressing as the social news from Europe can be, there are signs that such conjunctions are starting to proliferate. Musically, at least, countries like France and the United Kingdom are becoming places where the distinctions between “native” and immigrant, white and black are blurring to the point of irrelevance. While other parts of Europe, like Italy, remain more culturally conservative, the overall trend is definitely towards hybridization. And, while the likelihood of the German Karkadan lying down with its Italian counterpart may be remote, the fact that they share a name and a continent at least makes it easier to dream such a transgressive union.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Charlie Bertsch

More articles in

Arts and Culture

- Euphoria, Curiosity, Exile & the Ongoing Journey of a Hasidic Rebel: A Q & A with Shulem Deen

- Poet Q, Poet A: Jews Are Funny! Six Poets on Jewish Humor, Poetry & Activism and Survival

- Tackling Hate Speech With Textiles: Robin Atlas in New York for Tu B’Shvat

- Fiction: Angels Out of America

- When Is an Acceptance Speech Really a Speech About Acceptance?