Leftist Ethicist: Advice to Help “Offset” Gentrification in Chicago

My husband and I are thinking about buying a property in Chicago, but we are in a bit of a quandary. We know we are not going to be moving to the Lincoln Park area, or any other high-income neighborhood. Knowing that we will be gentrifying, we would like to “offset our footprint” if you will, like one might offset one’s carbon footprint by planting a tree or carpooling. This is most commonly done by buying a two-flat (that’s Chicagoan for a two-unit residential building), and opening up one unit for affordable housing. What if, however, we do not seem particularly suited for being landlords? In other words, are there other ways to “offset our footprint” besides becoming landlords?

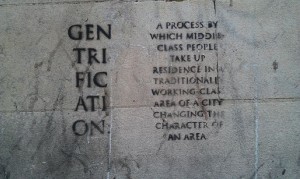

Gentrification is a central issue in the lives of almost all dwellers in major cities. Here’s what the late Neil Smith – distinguished professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and noted Marxist – said in “Gentrification in Brief”:

“Since the 1970s, gentrification has shifted from a marginal, fragmented process in the housing market to a large-scale, systematic and deliberate urban development policy…. Gentrification occurs in urban areas where prior disinvestment in the urban infrastructure creates neighborhoods that can be profitably redeveloped…. [It] has deepened as a comprehensive city-building strategy encompassing not just the residential market, but recreation, retail, employment, and the cultural economy.”

With a system so large and brutal, it’s good to throw a bunch of strategies for combating it on the table. That said, I really love this question, because I hadn’t heard about the practice of gentrifiers buying property and renting it out at affordable rates. Turns out, this practice is deeply rooted in an American Christian organization, the Christian Community Development Association, founded by Reverend John Perkins, a Mississippi-born, African-American civil rights activist. CCDA has three core tenants: relocation of people with privilege (historically white, but increasingly multiracial) to poor neighborhoods, reconciliation among races and classes, and redistribution, which can look like offering an extra unit in your home for a very affordable rate, opening a health clinic or starting a business and hiring locally. People with class privilege often commit to living in a low-income community for a decade, sending their children to local schools, attending local church services and finding ways to strengthen the community without displacing community members.

This is a really interesting and potentially community enhancing tactic, but this won’t change the larger forces and policies that create gentrification, and what often comes with it: the displacement of current residents who are priced out of their own neighborhood. The Leftist Ethicist reached out to Reverend Alexia Salvatierra, co-author of Faith Rooted Organizing, for her thoughts. As she pointed out, being a nice landlord won’t make a dent in the gentrification of your neighborhood. Since you don’t feel cut out to be a landlord, use the time and money instead to get involved in local community organizing efforts.

“The housing system isn’t working,” Rev. Salvatierra said. “If you are serious about offsetting your footprint, you have to participate in community organizing around rent control, sustainable development or supporting local community businesses by fighting alongside of them to keep their rents low.” You can start with checking out local neighborhood associations, community centers or faith-based organizations to see what organizing work is already happening. Many younger people don’t realize that most neighborhoods have community groups of long-term residents who are looking out for their block.

In Chicago, the Jewish Council on Urban Affairs has worked hand in hand with low-income communities on a variety of anti-gentrification strategies over its long history, chronicled by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz in “The Color of Jews: Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism.” In 1992, JCUA worked with organizers in Pilsen and Chinatown to fight a proposal to build huge parking lots in their neighborhoods during the World’s Fair. It also worked with Pilsen to prevent an industrial area that employed local workers from being redeveloped into a strip of high-end boutiques. More recently, JCUA has partnered with Community Development Corporations to build hundreds of affordable housing units in low-income neighborhoods.

As for everyone else, Rev. Salvatierra doesn’t pull punches for socially conscious people who choose not to get involved in organizing efforts in their community.

“People make friends with their neighbors as a way to ease the damage of gentrification,” she says. “If you aren’t actually willing to do something about gentrification, don’t move into a low-income neighborhood.”

The Leftist Ethicist is an advice column for Zeek readers who envision a more just world and act to create it. With a commitment to justice and progressive Jewish teaching (and a loving nod to the Bintel Brief), the Leftist Ethicist provides a space to raise questions, without judgment, and receive sensible solutions. The Leftist Ethicist is not intended as a replacement or substitute for financial, medical, legal or other professional advice. Send questions about ethical dilemmas to LeftistEthicist@Zeek.net.

Readers: I am interested in your impressions of the ethics of the CCDA strategy, which includes religious evangelicalism. And with gentrification raging in 2014, is this strategy for reconciliation still reconciliatory? What other strategies and actions can readers take or support? Please share your thoughts, links, and suggestions in the comments section!

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Mae Singerman

- Leftist Ethicist: Advice to Help “Offset” Gentrification in Chicago

- Plight of a Mentor: Cutthroat Vs. Collaborative for NextGen Women Leaders: The Leftist Ethicist

- Racism in the Art World: Avoid or Act? The Leftist Ethicist

- A-Listers for a Cause, Relative Creepiness, and Ethical Realtors: The Leftist Ethicist

- Moral Money Tips for Newlyweds, Avoiding Activist Burnout: The Leftist Ethicist

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!