The Hebrew Goddess: Complexity, Unity, Gender, and Society

The biblical religion which eventually became Judaism was but one of many authentic Israelite traditions. The priestly elite condemned those other traditions, banning their magical practices, outlawing their images, and insisting that God was only male, and only in the sky. But we today are not only their heirs, but also the heirs to those suppressed and marginalized voices who spoke of the earth, the goddess, and the sacred feminine. What does this mean for those of us who seek to create a Jewish identity that includes these voices?

In their new, radical, revolutionary prayer book, a group of modern kohanot – priestesses – has recovered, reinvented, and renewed some of these silenced voices to create a liturgy that is alive to the multiple energies of the manifest world. Not only is the result, the Kohenet Siddur, edited by Rabbi Jill Hammer and Holly Taya Shere, “not your father’s siddur” – this is a siddur which, if he were a traditionalist, your father would regard as heretical. In discussing the siddur project, Jill and I talked about nonduality and the Divine feminine, the difference between unity and nonduality, the surprising accord between polymorphism/polytheism and monism (and discord with monotheism), what’s meant by “returning to the womb,” goddess worship and complexity/hierarchy, Ken Wilber and the web of life, re-encountering the Divine masculine, and other fun stuff. Read on. -jm

Jay: Let’s start with by talking about the title of Raphael Patai’s seminal book, The Hebrew Goddess. Who is the Hebrew Goddess? What do we mean, conceptually or experientially, by this term? I noticed in the Kohenet siddur that the goddess seems to stand for nonduality, which as you know is a subject I’ve done a fair amount of work on lately. I have a somewhat different view: to me, the language of god/goddess is important precisely because it is a dyad. Now, goddess may indeed be the non-dividing, non-dyading principle in that dyad – but that is still in the context of a dyadic relationship. To me, to say that goddess stands for the nondual flattens out what’s interesting about the goddess as an entity and object of devotion. Another way of asking this is, why is the goddess female?

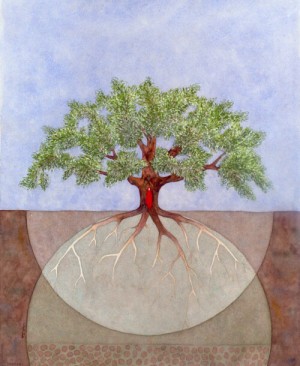

Jill:The Goddess as a feminine yet non-dual force partly has to do with the mammalian experience of womb/child/mother as a unity/multiplicity experience. It also has to do with the cycles of birth and death, with which the Goddess is almost invariably associated (while God-stuff often has to do with the transcendent, the infinite, and/or the hero’s journey through the cycles). I experience these characteristics deeply in my spiritual life, yet when I try to talk about them I feel I’m approaching gender essentialism.

I struggle a lot with the non-dual piece. My experience is that people (at least in American Goddess culture) see Goddess as non-dual and this distinguishes their experience from the general Western experience of God; however, saying “the feminine side of the non-dual” seems a bit absurd, since that by definition is dual.

Jay:Maybe it’s helpful to use the word “unitive” and “dualistic” as the pairing, and then “nondual” as that which includes both. I tried to make this distinction in my book, but I don’t think it came through. For example, a few people have told me”ooh, I had an experience of the nondual.” What they really mean is they had a unitive experience, a sense that everything is one and/or connnected. Whereas a nondual experience is… just this.

I think the womb piece is spot-on and it doesn’t feel essentialist to me. Wombs are pretty darn universal. Because of my own woman/man issues, I still experience the unitive as either non-gendered or as male. It feels like “me,” which feels male. But when I look inside that, I see the anxiety/discomfort about being in a (female) womb, which is probably related to my own sexuality.

Jill:The unitive vs. non-dual distinction is useful (and helpful to me in digesting my own experiences of both). I appreciate your sharing about your experience of the unitive and also about your discomfort with wombs– an issue I think many men and women share. I believe much of the levitical purity system deals with fear of the womb and fear of death, two issues which seem intertwined in Western myth. Thinking about your comments, I wonder how the queerness of many male mystics impacts this. (Not that straight guys don’t have issues too…)

Jay: One irony here is that “paganism” is at once more multi-theistic and more uni-theistic than monotheism. On the one hand, paganism includes lots of energies, deities, etc.; it’s very polymorphous, or even polytheist. On the other hand, in the pagan view, we’re all part of one web and not separate. Whereas, traditional monotheism has only one big Energy, but yet maintains that I’m separate from it . Monotheism seems like more of “one,” but it’s actually more of “two.”

This is similar to a phenomenon I’ve noticed in several unitive traditions. Strangely, though one might expect a radically iconoclastic emphasis on nothingness in nondual mystical traditions, in fact the opposite is the case: religious traditions which most embrace nonduality often embrace polytheism – Hinduism, for example. Classical theosophical Kabbalah also embraces a theological polymorphism when it posits a cosmos in which the higher contains the lower, the lower contains the higher, and lower forms of religious expression are seen as the highest form of nondual expression, since it is the dance the One does as the many.

Ken Wilber talks about these things a lot, but I feel like he’s a little too “male” to really get the web-of-life view he tends to disparage. One argument against web-of-life views is that the web-of-life is regressive (“back to the womb”) and not able to do much with real hierarchies, like complexity, or animal > plant > mineral. Of course, maybe that’s what some web/goddess people want. But I think it’s possible to have a back-to-the-womb piece that isn’t about going “back,” as in backwards, but more like getting “back in touch with, and then back out.” There can be a goddess model that includes hierarchies of complexity.

And, even if having both (i.e. both circle/web/feminine and line/hierarchy/,masculine) is desirable, there is also a question of balance. Let’s agree that what we want is 50% masculine, 50% feminine. Well, since we’re now at 98% masculine, “balance” really means “more feminine.” We could say “yes, of course we also want to include hierarchy and rationality and so on, but that’s not where we have to place emphasis right now because we’ve got plenty of that already, thanks.” I think this is what Wilberites tend not to get on their way up the hierarchy of life stagges- they’re an elite few, and maybe not so interested in moving the world from “stage 3” to “stage 4” if they’re already at “stage 6” or whatever. Whereas, when we are teaching actual people, our work has to be about moving to a stage that is itself not ultimate, but which is a much-needed next step from where 98% of the world is right now. We can worry about next steps later.

Jill: I’m right with you on the irony of monotheism (where there is one god but many things) and paganism (where there’s really only one thing).

Your words about the womb and Ken Wilber reminded me of something that has been transformative for me regarding the back-to-the-womb experience. One of my early Goddess experiences was studying with Layne Redmond, a percussionist who researches priestess/Goddess connections to drumming. While teaching about drumming as an echo of the maternal/fetal heartbeat, she noted the fact that ova—the actual eggs that will later produce children–are formed in a girl baby before she is born. This means that part of what became me was not only in my biological mother’s womb, but in my grandmother’s womb. This blew my mind. It completely transformed the way I thought about my body and the way I thought about time. It blows my mind even more now to think that if my daughter Raya has children, their earliest origin will have been in me. So for me, the idea of “back to the womb” is not regressive. It’s more of an anchor in time and space, and a reflection of the truth that our bodies and spirits blend; we’re literally not separate from others. This is true on all kinds of levels, but for humans, it’s the womb where this unitive experience is deeply physicalized.

While Shosh and I were visiting Newgrange and Knowth in Ireland, we saw how people five thousand years ago put immense time and resources into building womb-like dark tombs/shrines where the solstice light would fall once a year on the ashes of their dead loved ones. This seems so deeply related to the notion of the earth as the place of the seed, and the idea that the earth-womb (unlike the literal human womb) can bring life from what has died. That’s also the “back to the womb” piece in a non-regressive way.

As far as complexity goes, I don’t see the Goddess in Her most ancient forms as opposed to complexity: Inanna and Isis preside over social contracts, the arts of civilization, kingship, and many things which are hierarchical. The overarching principle seems to be that the Goddess transcends hierarchy, because everything is born and dies, no matter how simple or complex it is. But She doesn’t eliminate development or hierarchy. That would be contrary to Her work, which is creation (and ultimately destruction).

Jay:I didn’t know that about the womb memory – that is pretty amazing. I do think there’s a regressive feature to the idea of “back to the womb,” though, as it is usually taken to mean goingback to pre-differentiation, to infant-like oneness, etc. It’s regressive psychologically, but, as you point out, not ontologically.

I need to learn more about this issue. I see on reading my words that I’m still captive to the monotheistic myth that “paganism = orgiastic, while monotheism = rationalistic.” Clearly that is false. I think a lot of modern Goddess-worshipping people think similarly, though, and construct a fake goddess in the image of anti-rationalism. In this way they do disservice to the actual goddess figures which are trans-rational rather than sub-rational, and play into the mean-spirited critics of the movement.

Jill: Psychologically, at least for me and for many other women whose writing I’ve read, returning to the womb is about experiencing our own creativity and our desire to fulfill our potential– and the potential of the world, which we sense through the unitive mystical uterine experience. The return to the womb is the journey to the underworld, which is a complex and integrative journey acknowledging one’s separateness and one’s merging at once. It’s an engine for increasing emotional, spiritual, intellectual and physical fecundity (not necessarily biological fertility, though that’s part of it for some of us). It’s about entrainment, not about regression. Think of a drum circle. Being in the rhythm doesn’t eliminate “you,” it adds to you and puts you in context. Maybe for the male principle, returning to the womb feels like a regression or an escape, but for women, in my experience, it can be like taking a step into our own creative selves by entraining with the universe.

In Ireland, we went to the cave of Oweynagat, which I was telling you about: it’s a cave that looks like a vaginal canal with a uterus at the end. There is a birthing stone there too. It’s considered the dwelling place of the Morrigan (a death and magic goddess) or Maeve (a sex, fertility, land, and kingship-granting goddess). We sat there in darkness, and even though I am a claustrophobe, I was completely at peace inside Mother Earth. The astonishing thing is that the two women present, after we left the cave, both began bleeding (I haven’t bled in over two years due to being a nursing mother, so this really was wild). That’s what I mean by entrainment. The womb doesn’t eliminate the individual; it re-awakens the fertile potential in the individual.

I want to talk about another subject, though. I’ve spent a lot of time the last few months thinking about the divine masculine and re-integrating that into my self-concept. For me, the divine masculine often corresponds with a sense of being supported, loved, or guided in my specificity (my sense of the divine feminine is much more about embodying and accepting the whole). I’ve also been thinking about the ways the male reproductive process (in which seed has to be given to another separate being) might relate to “masculine” kinds of spirituality that emphasize the letting go of attachment and/or the giving up of control to a higher power. These are just stray thoughts and not at all formed, but I am curious about how a later version of our siddur might open up the question of masculine and feminine energies for the individuals who use it.

My current question about balance is: do both men and women need 50%/50%, or does the world need that, while the balance for specific men and women might be different?

Jay: On the question of balance, I think both men and women need to be in touch with some of each, but I would never want to prescribe a ratio. In any case, all of men and women also need 100% of a self-construct not polluted by sexism. For example, Ann Coulter would say that she is very feminine by being a pre-feminist woman. (Notwithstanding the obvious contradiction of saying so as a careerist and ambitious writer.) Yet I would say that, while “pre-feminism” may indeed be a form of femininity, it is a form of femininity that is part of the subjugating process of sexism. So I do actually want to de-legitimize it somewhat, at least in terms of its relationship to an ideal. If Coulter has really gone through the process, done the inner work, broken down all the walls, and come out of it willingly saying “yes, I experience my femininity as wanting to be Taken by a Strong Man,” then baruch hashem. I have met people like that in the queer community. But I suspect her story is somewhat different and if she were drinking ayahuasca, she would be horrified at what she saw.

I want to make another point about balance. I think the many men who kvetch about kohenet not being “open” to them need to chillax, remember their privilege, and be quiet. And I think the work you are doing in kohenet vis-a-vis women is just beginning. Yes, at some point there needs to be a more subtle and more integrated relation to the masculine within the kohenet practice and text. But I think that point can wait awhile. If it organically evolves from the many women doing the work, as part of their process, of course. But at the moment, I’m interested in kohenet-masculinity only to the extent that it informs kohenet-femininity.

I’m afraid I’m a masculine-spirituality essentialist here. I think masculine spirituality is connected with building, doing, big tall buildings, standing on top of the mountain, as well as violence, war, domination, hierarchy, strength, linearity. To me, anything that is about letting go or giving up is about relinquishing control and thus a necessary counterweight to masculinity, rather than an expression of it. Personally, and I think this is true for many men, the reproductive process still seems to end with insemination. That is, of course, completely ridiculous. But I think that for many men, the subsequent nine months of work are rendered almost invisible, so much so that it’s like ejaculation->birth. I mean, whole civilizations refer to children as a man’s “seed”! It pains me that, as a gay man, even if I have children, the invisibility of the birthing process is likely to be even greater.

Jill:This is very powerful, what you’re saying here. This may be related to the way women have a hard time not giving away the store– we’re trained to nurture, so being told that we’re focusing on ourselves too much is triggering. And yet– women have an internalized masculine that we need to deal with, not run away from. We have fathers, brothers, lovers, sons, and male-introjects, and these relationships are part of who we are.

As far as Ann Coulter , I’m reading a book by Sue Monk Kidd, The Dance of the Dissident Daughter (She’s also the author of the Secret Life of Bees). Monk Kidd deals with many of these issues in sophisticated and real ways. One of the things she talks about is the “favored daughter” syndrome– the desire of many women to reject the feminine so the father will approve of them. She sees this in religious women who defend the patriarchal system vehemently, colluding in the oppression of women, all so the father will see them as worthwhile. A mother who is identified with the patriarchy will also raise her daughter in this way, rejecting her female self and trying to make her conform to the patriarchal norms. This is the kind of psychological process than can create a vehement anti-feminist– or, if the daughter’s female self rebels, a powerful feminist.

Monk Kidd suggests this process has to be reversed through (you guessed it) a return to the womb and a re-initiation into the self. I think the role of initiation in becoming a Goddess-connected person is very important; most Goddess-following people I know have an initiation story.

I too experience the Divine masculine as being about building and achieving. I do think that the drive to achieve is connected to the frailty of human life. We build because we want to last, even though we can’t. For me, this feels connected to the male process of emitting seed, which is ephemeral but has the potential to create life. This seems connected to the figure of Christ, who dies to create eternal life, or the ideas of the Buddha, who encourages non-attachment and yet deep engagement in the world.

But I hear what you are saying about ejaculation -> birth. It’s so powerful to think about the problem this entails for one’s consciousness of human development (and your personal pain is moving to me too). I suppose this is how Western religion manages to elide the importance of women in making human beings; what women do is seen as secondary, bizarre as that is in the face of biology. In a similar act of forgetting, women’s other creativities– literary, theological, artistic, agricultural, medical, etc.– are rendered invisible.

Jay: That’s why the Kohenet siddur is so powerful—women’s creativity made visible, goddess made visible.

#

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Jay MichaelsonJill Hammer

More articles in

Faith and Practice

- To-Do List for the Social Justice Movement: Cultivate Compassion, Emphasize Connections & Mourn Losses (Don’t Just Celebrate Triumphs)

- Inside the Looking Glass: Writing My Way Through Two Very Different Jewish Journeys

- What Is Mine? Finding Humbleness, Not Entitlement, in Shmita

- Engaging With the Days of Awe: A Personal Writing Ritual in Five Questions

- The Internet Confessional Goes to the Goats