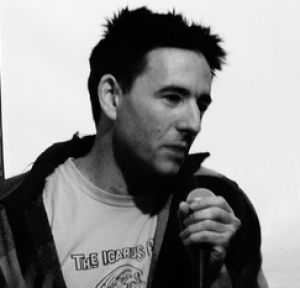

Madness, Mindfulness & Judaism: Meet Sascha Altman DuBrul

I met Sascha Altman DuBrul nearly 20 years ago when we were both punk rock kids hanging out at ABC No Rio on the Lower East Side, making zines and burning to clasp the ecstatic core of existence and change the world. He’s been a soul brother of mine ever since then, and in the ensuing years I’ve often stood back and beheld his life with wonder as its wound and twisted its wild way through squats, freight train yards, day labor sites, anarchist infoshops, tear-gassed protests, guerrilla gardens, radical circuses, renegade street parties, country farms, dead friends’ memorials, jail cells, psych wards, ashrams and university lecterns.

He’s told his stories in zines like “The Secret Life of White People,” and “El Otro Lado,” dog-eared copies of which circulate throughout the anarchist underground, and now he’s knitted his stories together in a book, Maps to the Other Side. It’s a rollicking tale of his adventures as well as a raw and deeply vulnerable account of his psychotic breakdowns, suicidal depressions, hospitalizations, numbing treatment regimens and, ultimately, his awakening to transform the entire conversation about mental illness by co-founding the Icarus Project, a radical mental health support network and community that has thrived for ten years. I spoke with Sascha about madness, social justice and his recently sparked Jewish identity on the eve of his cross-country book tour.

Jennifer Bleyer: I found myself wondering, after reading the book, how you reconcile your critique of bio-psychiatry with your acceptance of your own bipolar diagnosis? It seems like you say, “Yes, I need to take psychiatric drugs, but at the same time I reject the mental health establishment saying that the problem is all in my brain.”

Sascha Altman DuBrul: The way I reconcile them is by having a nuanced perspective. I’ve had 10 years of experience crossing paths with thousands of people, and one thing that’s become very clear is how different their experiences can be, and how important it is to honor the differences. In the period of time when we started the Icarus Project, there was an explosion in bipolar diagnoses. So many people have gotten that diagnosis, people who it’s just not appropriate for, people who often have intense trauma histories, and the diagnosis ends up leaving them disempowered and feeling like the only way they can speak about what they’ve experienced is in terms of this biological brain formula. I think my critique is important because it’s complex: I both reject the overarching bio-psychiatric paradigm, and I accept that the drugs have the potential to be really helpful. My main argument is that bio-psychiatry completely ignores social and economic and political contexts. It’s really convenient for the powers that be to not have to acknowledge that people are hurting because of power and oppression and environmental devastation.

How would you trace the evolution of your feelings about the notion of Mad Pride, this idea that someone can be empowered by and even proud of so-called mental illness?

There’s something really beautiful and potentially empowering in the idea of difference as a point of pride. But sometimes, you can start off with a really good idea and it might end up being a box you get yourself stuck in. The conclusion I drew with Mad Pride was basically, that like any movement where you’re trying to bring a group of marginalized people together, it’s good to focus on what you have in common and how you’re different than others as a first step. But once you do that, people don’t need one more identity to latch on to. We live in a society where people really struggle for a sense of identity, and yeah, “madness” can work for some. But in the end, madness is not what I’m proud of. Yes, there’s something about navigating the space between brilliance and madness and understanding that there’s a role for extreme states of consciousness that we can be proud of. But in terms of building a movement that people can get around? “Mad Pride” sounds sexy, but it doesn’t really hold much weight. I’m way more interested in something along the lines of a Human Potential Movement. A movement that revels in our differences, our sensitivities and gifts, but focuses on health and wellness.

What brought that interest about?

The last time I had a psychotic breakdown, I ended up living in a yoga ashram for a year, which turned out to be a really good thing for me. I not only developed a meditation practice and a type of spiritual discipline for the first time in my life, but I learned about the history of healing and transformation movements in the 1960s and ’70s. There was this whole intersection of Eastern spiritual practices and Western psychotherapy and all of these interesting things came out of it: humanistic and transpersonal psychology, Gestalt therapy, encounter groups. And so much of that stuff got crushed by the rise of bio-psychiatry in the 1980s. So much so that many of us don’t even know it ever existed. In some ways, I dropped the idea of Mad Pride when I realized that there’s a way more interesting story that has to do with helping people find their potential. For my friends and me in Icarus these days, there’s a lot of thinking about how to have something along the lines of a Collective Human Potential Movement. You have to start from a place where you recognize that there are fundamental problems with society, and then embrace the visions and the visionaries who have the power to see a different world.

How do you imagine bringing these ideas more into the social justice world?

I’d want to see an approach like the organization Generative Somatics, which is based in the Bay Area of California, where I live. In courses they teach, like Somatics and Trauma, you’re basically getting rooms full of people together, helping them break down the social armor they have and then learn skills to connect in ways that we just don’t learn in this society. When Occupy happened, I was part of this group called Occupy Manifest that was doing just that — taking social justice activists and training them to feel from their hearts. When I think about the movements I was a part of as a young man and a teenager, I think of how good it would have been if we had had more skills like that in being able to relate to each other.

You’ve had a kind of personal Jewish awakening in recent years, which is touched on a little bit in your book. Can you talk about what brought that about?

I was raised in a pretty secular Jewish household on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where progressive Democratic politics replaced the role that religion might have had in an earlier time. I didn’t realize until I got older how common that was in the place I was raised. After I got out of the psych hospital the last time, I found myself on an island in the Bahamas, living in a tent at an ashram and surrounded by Israelis who had done their military service and were now living on this island, chanting Sanskrit. They were Jews, they just weren’t talking about Judaism — they were talking about Krishna and Vishnu and Shiva. They were reading these ancient texts and exploring the layers of meaning within them. And I loved the study and the chanting. I grew up in a home with a lot of books and interest in reading, so I think it was a natural progression that I got interested in studying Jewish texts.

Since I left that ashram, I went back to college and spent a lot of time studying European and Jewish history. I was this adult guy reading the Torah for the first time, and the stories were actually horrifying to me. I longed for making a connection to them, but I’m still looking for what that is. I often end up feeling like I’m just studying some culture that belongs to me but is also outside of myself, like I’ll go to synagogue and feel like an anthropologist. I’m grateful to be part of the story, for all the complexities and nuances, but I’m still trying to figure out where I fit into it.

Of course, that feeling of outsiderness is so Jewish.

For sure, that’s the thing. I never realized how fucking Jewish I was! At some point I had this whole revelation that I grew up in the punk scene, and there are so many striking similarities between the Jews and the punks. I gravitated towards people who felt like they were different than everyone else. The core identity of our community was of outsiderness and being oppressed by the larger world. We put obscure insignias on our clothes that were just for each other. We had a special diet that separated us from others. We had traditions that led back to Europe that were veiled in mystery. We listened to hard-to-penetrate music and read obscure publications that stayed within our scene. On Friday and Saturday nights, we’d go to these buildings on the Lower East Side and get together and sing and dance and eat food. And there was even, I dare say, some sense of being chosen, of being better than others because we were closer to a set of truths than the mainstream population. I clearly was longing for having a culture of my own that was special and different, so I sought it out and found it with the punks. Imagine my surprise as an adult when I realized how Jewish I was acting!

Many of the questions that come up for me about Judaism in the 21st century have to do with what happens to a group of oppressed people when they finally get some power. What do they do with that? How does oppression both have the potential to sensitize us to others suffering, and how does it create blind spots that make us act out the role of the oppressor all over again on someone else? I’m still figuring out what it means to be a Jew in this context, but I’m grateful for the challenge. I find the complexity of identity to feel like home. I aspire to finding a group of Jews who have a solid stake in being Jewish, and also recognize that there are a lot of changes happening in the world, and we can be a part of changing the story.

I love the end of the book where you talk about becoming a mentor. In that vein, what would you advise a young activist who’s just coming up now, someone like you 20 years ago?

I would say look for the people who are doing interesting things that you’re drawn to and find a way to attach yourself to them! Having experienced mentors that you can respect and trust — whether in school or on the street or on a farm — is so important! And then find ways where you can be a mentor to others! We often learn by having to teach other people. If you are a really sensitive person who wants to do good in the world, recognize and honor your sensitivities! Find other people who appreciate you for who you are. Taking really good care of yourself ends up being a key part of the struggle for justice and transformation of the world. Also, it sounds funny to say, but the most important lessons are often in the scariest places. The things we’re scared of or repulsed by almost inevitably have really good lessons for us. And social media technology is amazing for networking, but it’s no substitute for hanging out with people face to face. By whatever means, make sure you do things where you’re actually hanging out with people, whether it’s cooking food or making art or talking to your neighbors, and have groups of people who you can get together and talk about your experiences with. That’s the future.

- For more about the book tour – including stops at the International Society for Psychological and Social Approaches to Psychosis at NYU on April 20th and a book launch at Bluestockings on April 25th, visit the Icarus Project.*

Jennifer Bleyer was active in Riot Grrrl, wrote the punk travel zine “Gogglebox” and edited the Jewish punk zine “Mazeltov Cocktail” about 20 years ago. Since then she’s been doing other things like starting Heeb Magazine, writing for the New York Times, and raising children.

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!