The Leftist Ethicist — June Edition

The Leftist Ethicist is an advice column for Zeek readers who envision a more just world and act to create it. With a commitment to justice and progressive Jewish teaching (and a loving nod to the Bintel Brief), the Leftist Ethicist provides a space to raise questions, without judgment, and receive sensible solutions.

I am a cisgender(^) man, and my girlfriend is a cisgender woman. We have been dating for a couple of months. We live in a small city in the Midwest. In order to be an ally to queer people, I don’t do PDA (public displays of affection) with my girlfriend. I decided to follow this path because it isn’t really safe for queer people to demonstrate affection publicly, so why should straight people have this privilege? Also, I know it can be triggering for queer people who can’t express their love publicly to have straight people all up on each other. My girlfriend is not into my whole theory. I don’t care that much about PDA anyway, so it isn’t much of a loss for me. This is causing friction in an otherwise seemingly good new relationship. What should I do?

Your question raises good points, especially with so many recent violent attacks on people for their perceived sexual orientation like the ones in Ohio and New York. LGBT people still make calculations every day about how “out” to be in public. Is it safe to hold hands, dress in clothing that matches their identity, or talk openly about love? These daily, quiet calculations can lead to resentment of hands-y straight couples who don’t think twice about touching, even when you sometimes wish they would.

Here’s the problem: Your tactic doesn’t actually make your city safer for queer people to express themselves, and that is the ultimate goal, right? Beyond that, it could destroy your good relationship.

I reached out to Matillda Bernstein Sycamore — writer, editor, anti-assimilationist queer activist and author of a new memoir, “The End of San Francisco” — to get her take. She suggested that you keep the ball, but run in the opposite direction. Instead of denying affection to your girlfriend, “show public affection with people who aren’t your sexual partner, too. Create more choices and more fluidity.” With their permission, link arms, hold hands or put your arm around your men friends. Yes, this will create a new conversation and shifts in relationships, but it sounds like you’re up for thoughtful dialogue on boundaries and why affection is a political act. Your small public gestures of affection could be a cue for that cute lesbian couple in line for the movies to finally stand close together or hold hands.

Beyond this, keep doing what you probably already do: Speak up when you hear homophobic comments, support friends and family when they come out, and give your girlfriend a kiss (in public!).

^Cisgender is a term used by someone who identifies with the gender/sex they were assigned at birth. Someone who identifies as a different gender/sex than they were assigned at birth is transgender.*

Recently, I was on a flight from Chicago to New York. Sitting next to me was a middle-aged Muslim man. I’m liberal in my worldview, but also neurotic. A few minutes after takeoff, he got up and started messing with his bag and then headed to the bathroom. I started to freak out, planning my funeral. Of course, nothing happened and he turned out to be a nice guy. I feel guilty about my suspicion, and in my very liberal Jewish social group I would be berated for even expressing this fear. It happens kind of regularly, but I just pretend like it doesn’t. Am I a horrible person?

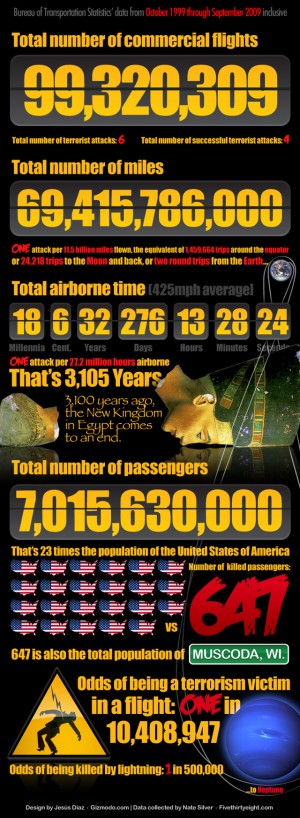

You’re not horrible, but you might not be very compassionate, either. Almost a quarter of the world’s population is Muslim. A minuscule percentage are terrorists. It isn’t reasonable to plan your funeral every time a man wearing a kufi hat decides to visit his family out of state. If anyone has reason to fear, it is Muslims, many of whom experience hours of questioning, intrusive screening processes and suspicious looks (ahem) when they fly.

As unlikely as you are to be affected by terrorism (http://bit.ly/11lvnU8), you aren’t alone in the fear. “It is inevitable that all of us have absorbed some amount of racism. We all grew up in a society that is fundamentally biased against certain types of people,” says Rabbi Jill Jacobs, executive director of T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights, which has worked closely with rabbis, Jewish communities, and Muslim communities to stop religious discrimination. “It’s important that this person recognizes that, and also important that she not to jump to conclusions about the traveler based only on religious affiliation.”

To help overcome your fear, here is some homework. If you’re Chicago-based, check out the Jewish Council on Urban Affairs’s Jewish-Muslim Community Building Initiative. In New York, there’s Jews against Islamophobia. Attend an event put on by one of these groups or an event led by a Muslim organization. While there, notice the emotions and thoughts that come up. Don’t judge yourself for what you notice. Afterward, commit one hour to reflecting on your experience, the root cause of your fear on the plane and what you learned growing up about Muslims.

Keep up your personal exploration and your attempts to learn about Muslim Americans until you have a more complex view — and maybe even a few Muslim acquaintances. Your fear may never disappear completely. However, you can get to a point where you see what your anxiety is: a well-worn story that doesn’t reflect the realities of your own lived experiences.

Thanks to Rabbi Jill Jacobs and Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore for their insights!

The Leftist Ethicist is not intended as a replacement or substitute for financial, medical, legal or other professional advice. It’s just my opinion! What’s yours? Talk back in the comments! Send questions about ethical dilemmas to LeftistEthicist@Zeek.net.

Want more? Visit May’s Leftist Ethicist or April’s!

![[the current issue of ZEEK]](../../image/2/100/0/5/uploads/leftistethicistgraphic-52842c6a.png)

- 5000 Pages of Zeek

- Founded in 2001, Zeek was the first Jewish online magazine, and we have over 5000 pages online to prove it, all available free of charge. Read more in the Archive.

More articles by

Mae Singerman

- Leftist Ethicist: Advice to Help “Offset” Gentrification in Chicago

- Plight of a Mentor: Cutthroat Vs. Collaborative for NextGen Women Leaders: The Leftist Ethicist

- Racism in the Art World: Avoid or Act? The Leftist Ethicist

- A-Listers for a Cause, Relative Creepiness, and Ethical Realtors: The Leftist Ethicist

- Moral Money Tips for Newlyweds, Avoiding Activist Burnout: The Leftist Ethicist

More articles in

Life and Action

- Purim’s Power: Despite the Consequences –The Jewish Push for LGBT Rights, Part 3

- Love Sustains: How My Everyday Practices Make My Everyday Activism Possible

- Ten Things You Should Know About ZEEK & Why We Need You Now

- A ZEEK Hanukkah Roundup: Act, Fry, Give, Sing, Laugh, Reflect, Plan Your Power, Read

- Call for Submissions! Write about Resistance!